The Writer’s Guide to Castle Defenses

Posted on November 12, 2021 5 Comments

Castles have been romanticized for centuries, to the point where we forget their use. First, they were a home. Second, they were a series of carefully designed kill zones.

Today I will cover the features most seen in castles and their purpose. I will limit this article to medieval Europe since that is when and where most castles are located and because that is where most of my knowledge lies.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Castle Features

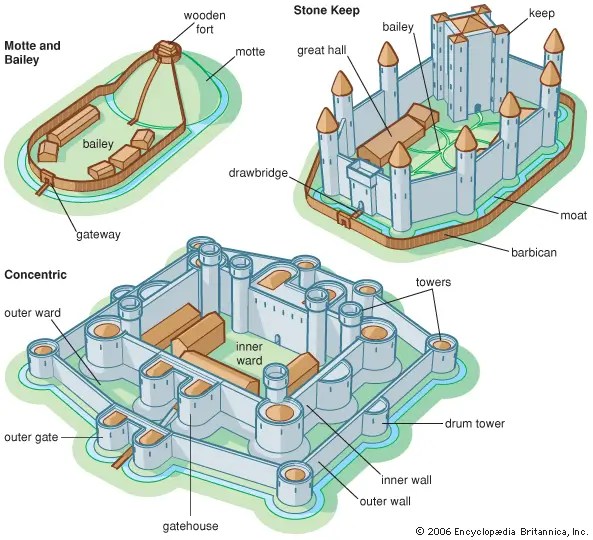

Keep – A keep was a fortified tower or building. It was in the most defensible part of the castle. It was as a home for the residing lord, his family, and household. [1] In most early castles, the keep consisted of only a few rooms. Sometimes only a screen would separate the Great Hall from the lord’s bedroom. [2] However, as castles became bigger and more complex, the keep became larger. Later castles had buildings ringed around a central courtyard or enceinte instead of a single keep. [3] In motte-and-bailey castles, the keep is set on top of a motte, an earthen mound.

Within the keep was located the Great Hall, a large room used for greeting guests, feasting, social gatherings and meetings, and legal trials.

Bailey or Ward – The bailey or ward is an open space enclosed by a curtain wall. All castles have at least one. Its primary function was to leave invaders exposed to attack from the keep and battlements. Baileys often contained buildings such as barracks, stables, kitchens, storerooms, chapels, and workshops. The well was also in the bailey. As castles became more complex, they used a series of baileys for protection. The central bailey was called the inner bailey, the further out, the outer bailey. A bailey off to one side was called a nether bailey.

Curtain Walls – Curtain walls surrounded the baileys. A typical curtain wall was 10 feet thick (3 m) and 39 feet tall (12 m). They had to be tall enough that it was difficult to scale them with ladders and thick enough to withstand bombardment from siege engines. Besides going over or through, curtain walls were vulnerable to tunneling, known as sapping. The sappers would either tunnel under the walls, coming up inside the bailey, or create a void under the wall, causing it to collapse.

Gatehouse – A gatehouse was a fortified entrance. Because of the vulnerability of the gate, they often had flanking towers that stuck out further than the gatehouse, allowing the defenders to fire upon attackers. [4] The gates opened outward, so that anyone trying to force them in would work against the hinges. Most gatehouses had at least two sets of gates. Heavily fortified gatehouses were known as barbicans.

Portcullises were heavily latticed gates that were opened by being raised vertically. Their chief advantage was that they could be closed quickly by a single person. They were often set inside the gatehouse, behind the outer set of gates. They could trap attackers inside the gatehouse.

Moat – Moats became a popular way to protect curtain walls. They could be dry or filled with water. Moats were crossed either by a flying bridge or a drawbridge. [5] Moats were not limited to the outside of a castle. Some castles have moats inside the curtain walls, protecting the keep, for example.

Postern – A postern gate or door was a small, hidden door in the curtain wall that allowed people to sneak in and out of a castle. During a siege, messengers or soldiers could leave and enter without the knowledge of the attackers.

Battlements

Battlements are defensive architecture built into curtain walls and towers. The most familiar type of battlements are crenelations, the tooth-like structures of alternating spaces. The upright part is called a merlon with the space called a crenel. Merlons were the height of a person and provided cover from incoming fire. Crenels allowed archers to fire back.

Machicolations were battlements that extended beyond the top of a curtain wall or tower, creating an opening through which stones, hot sand, and other nasty surprises could be dropped on people at the base of the walls. [6]

Arrow Slits

Arrow slits, also known as loopholes, were vertical openings in outer walls that archers and crossbowmen used to fire on attackers. The walls were angled on either side of the opening, providing a wide field of fire. [7] Plus, the narrow slit was a small target, protecting the archer inside.

Murder Holes

Murder holes were similar in function to machicolations, except they were in the ceilings of gatehouses or buildings. Boiling water, hot sand, or stones could be dropped onto invaders.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or write a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox, every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2021 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Cathcart King, David James (1988). The Castle in England and Wales: An interpretative history. London, UK: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-918400-08-2. [2] Barthélemy, Dominique (1988). “Civilizing the fortress: Eleventh to fourteenth century”. In Duby, Georges (ed.). A History of Private Life: Volume II · Revelations of the Medieval World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University [via] Belknap Press. pp. 397–423. ISBN 978-0-674-40001-6. [3] Friar, Stephen (2003). The Sutton Companion to Castles. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-3994-2. [4] Friar, Stephen (2003). The Sutton Companion to Castles. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-3994-2. [5] Cathcart King, David James (1988). The Castle in England and Wales: An interpretative history. London, UK: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-918400-08-2. [6] Jaccarini, C. J. (2002). “Il-Muxrabija: Wirt l-Izlam fil-Gzejjer Maltin” (PDF). L-Imnara (in Maltese). Ghaqda Maltija tal-Folklor. 7 (1): 17–22. [7] Friar, Stephen (2003). The Sutton Companion to Castles. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-3994-2.

The Writer’s Guide to Castles

Posted on November 5, 2021 6 Comments

From the Red Keep to Cair Paravel to Skyhold, castles have loomed large in fantasy and are a familiar part of the landscape of movies, TV shows, video games, and books. They are a favorite among writers and often grab the imagination of readers and viewers. However, unless you live in Europe, most writers don’t have the opportunity to visit a real castle. These fortresses were built with an intentional purpose, clever engineering, and impressive technology. The fact that so many of them are still standing today is a testament to the quality of their construction.

Today I will be diving into the basics of castles.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Definition

The term “castle” gets tossed around quite a bit but what is a castle? What makes it different from a palace or fortress? Historians usually define a castle as a private fortified residence. [1] They were commonly held individually by members of the nobility or the royal family since land ownership and a lot of money for construction and upkeep were required. [2] The main way to acquire land in medieval Europe was to be gifted it by the monarch, usually as a reward for loyal service. There was also the expectation of continued military service from the lord and his vassals. [3] Ownership was hereditary, usually passing to the oldest son. This type of inheritance is known as patrilineal.

Purpose

The castle served multiple purposes. First, it was a residence, housing the owner, their family, and household. Second, it was an administrative center from which to oversee the owner’s lands. Third, it was a military base from which soldiers could attack and retreat to. [4]

Evolution

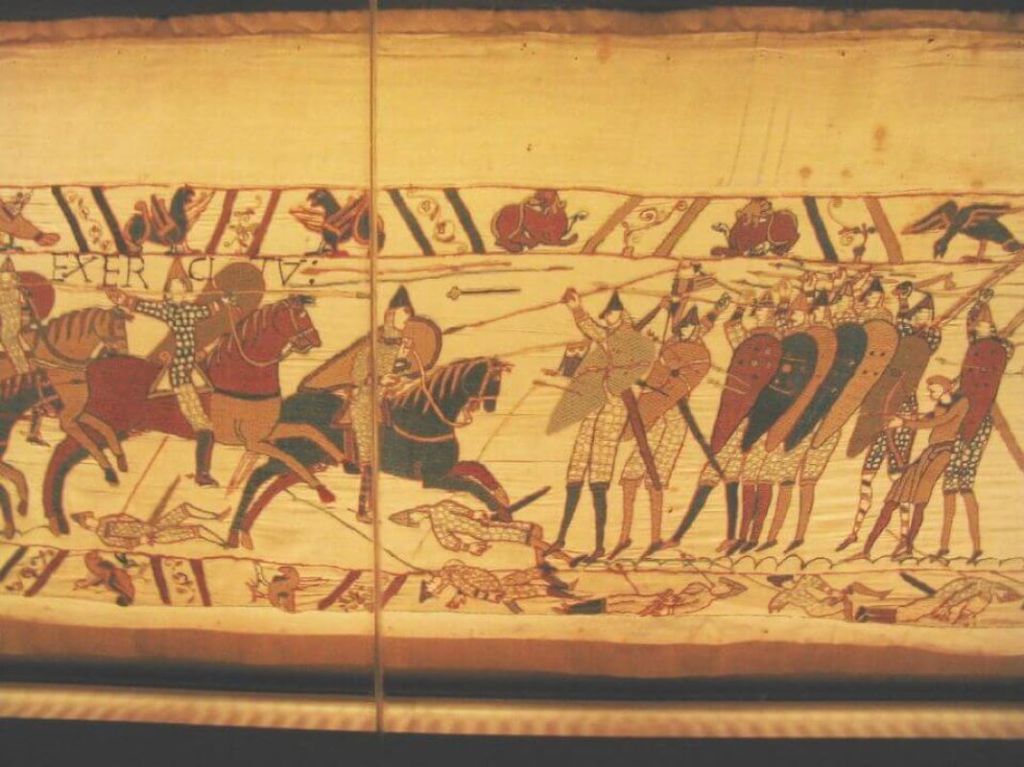

Walled fortifications are incredibly old and were built in the Indus Valley, Egypt, and China. There is some debate regarding when the first castles were built. The ancestors of castles were likely the fortified homes of lords. The most common defenses were walls and earthworks. The first castles were often made of wood.

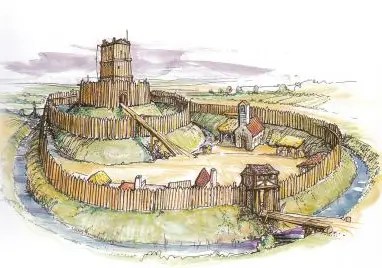

Notice it is made of wood and the attackers are trying to set it on fire. Photo source.

The first type of castle is a motte-and-bailey castle. A motte is an earthen mound, usually flattened at the top. It could be natural or manmade. [5] They ranged in height from 10 to 100 feet (3-30 m) and in diameter from 100 to 300 feet (30-90 m) [6] On top of the motte, was built a keep, which housed the lord, his family, and household. The early keeps were constructed of wood, which made them susceptible to fire. Over time, stone became the more common building material. The motte and keep were surrounded by a wall or palisade that enclosed the bailey. It was an open space that keep attackers at a distance and housed various buildings such as the stables, forge, workshops, storehouses, barracks, and kitchen. [7] Motte-and-bailey castles were first built in northern Europe in the 10th century, spreading to southern Europe throughout the following century. The Normans introduced them to England when they invaded, and they were adopted through Britain and Ireland during the 12th and 13th centuries. The design was surpassed by others by the end of the 13th century.

Castles continued to evolve from the motte-and-bailey. The biggest advance was replacing wood with stone. This happened slowly and unevenly across Europe since stone was harder to move and lift. There was often a mixing of the two. For example, a keep could be stone, but the wall would be made of wood.

Over time, castle design became more sophisticated. Walls were added, creating more baileys. Gatehouses and barbicans protected the passages through these walls. The entrance to the keep was moved to the second floor for security. Crenellations were added to the walls to protect the defenders. I will be covering the defensive features and parts of castles in my next article.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2021 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Coulson, Charles (2003). Castles in Medieval Society: Fortresses in England, France, and Ireland in the Central Middle Ages. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-927363-4. [2] Liddiard, Robert (2005). Castles in Context: Power, symbolism and landscape, 1066 to 1500. Macclesfield, UK: Windgather Press Ltd. ISBN 0-9545575-2-2. [3] Herlihy, David (1970). The History of Feudalism. London, UK: Humanities Press. ISBN 0-391-00901-X. [4] Friar, Stephen (2003). The Sutton Companion to Castles. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-3994-2. [5] Toy, p.52; Brown (1962), p.24. [6] Toy, p.52. [7] Meulemeester, p.105; Cooper, p.18; Butler, p.13.

The Writer’s Guide to Shields

Posted on October 29, 2021 114 Comments

Today I will be covering some of the most common misconceptions of shields that I see in movies, TV shows, and books. Again, my focus is on medieval Europe since that is where most of my expertise is.

If you want a guide to types of medieval shields, please visit my previous post here.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Use in Battle

There were two main uses of the shield: personal protection and group formations.

Personal protection is exactly what it sounds like: an individual using a shield to protect himself. Group formations, such as the shield wall or the Roman testudo, were used on the battlefield. They were especially effective against cavalry charges or volleys of arrows.

However, the shield wasn’t only used for defense. It could also be used as a weapon. The shield bash has become a staple in video games, movies, TV shows, and books. However, we have limited information regarding how often it was actually used during the medieval period.

Tactics

For individual use, there are multiple tactics. A combatant can use their shield as moving protection, meaning that they can rotate it, opening it like a door, to provide opportunities to strike. Since it is usually held out in front, it provides almost complete coverage. The pointed bottom of the Norman kite shield can be angled toward an opponent, keeping them at even further distance than other types of shields.

Multiple types of weapons can be used in the main hand including swords, axes, spears, knives, and batons.

Writer’s Tip: Swords and axes have commonly been paired with shields. I would love to see other weapons, especially the spear, which is incredibly effective when paired with a shield because of the longer reach.

The most familiar group tactic is the shield wall. It was also the most used in history, likely because it was effective and didn’t require a lot of training. Often strapped shields were used because this method put the shield off center and allowed it to overlap with the one on the bearer’s right. This interlinking made the shield wall stronger. The shield wall could also be formed into V and slanted half V shapes. A V pointed at the enemy is an enfilade while one pointed away is a defilade. [1] There is also the tortoise or testudo formation that was developed by the Romans. Another tactic was the hedgehog, a circular formation that could also incorporate archers and polearms.

Effectiveness

Just like armor, a shield was not perfect protection against an incoming strike. The effectiveness was heavily dependent on the type of attack and the construction of the shield. Shields were at their most effective when they were used to deflect incoming attacks, dissipating the energy rather than completely absorbing it. [2]

I recommend this video about the effectiveness of shields against arrows.

Construction

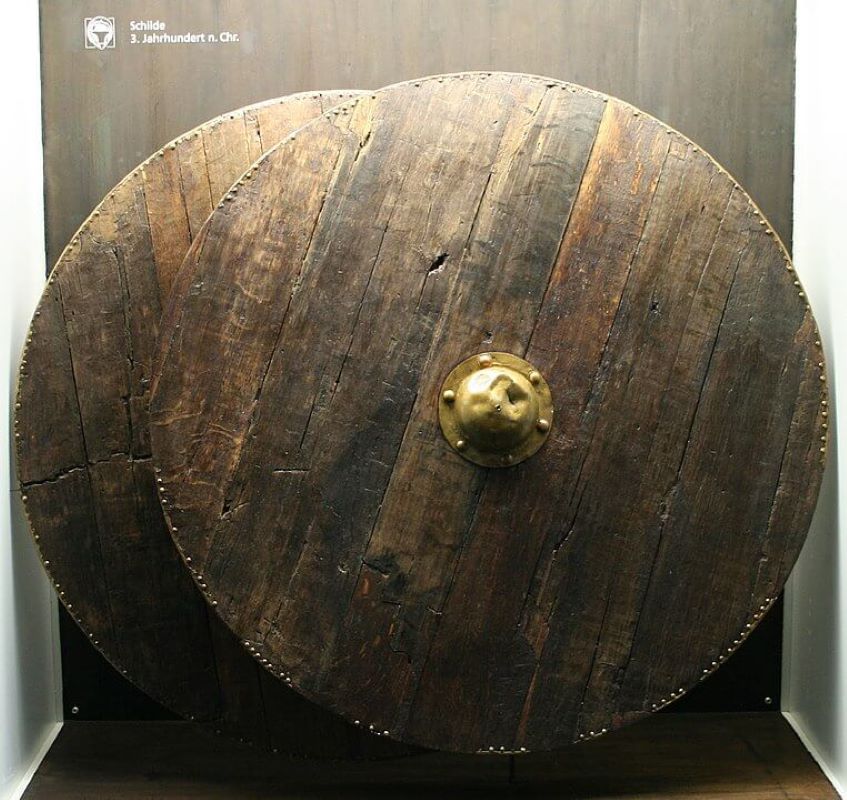

The construction of shields varied greatly depending on period and location. Early shields were usually just planks of wood held together by slats on the back. Later, they were covered with leather or canvas and could have a leather or metal rim. Further into the Middle Ages, shields were made completely of metal. Shields from other parts of the world were made of hide or wicker.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2021 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Marine Rifle Squad. United States Marine Corps. 2007-03-01. p. 2.10. ISBN 978-1-60206-063-0. [2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I1LScbpp9vM&t=179s

The Writer’s Guide to Types of Shields

Posted on October 22, 2021 127 Comments

The shield is almost as iconic as the sword when it comes to fiction and legend. Just like the sword, since it is not a commonly encountered item, most modern writers are lacking in accurate information. There is unfortunately a lot of misinformation presented as fact.

Today we will be looking at types of shields. My focus will mainly be on medieval Europe since that is when and where most of my knowledge is and because most depictions of shields in movies, TV shows, and books are from this period.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Types of Grip

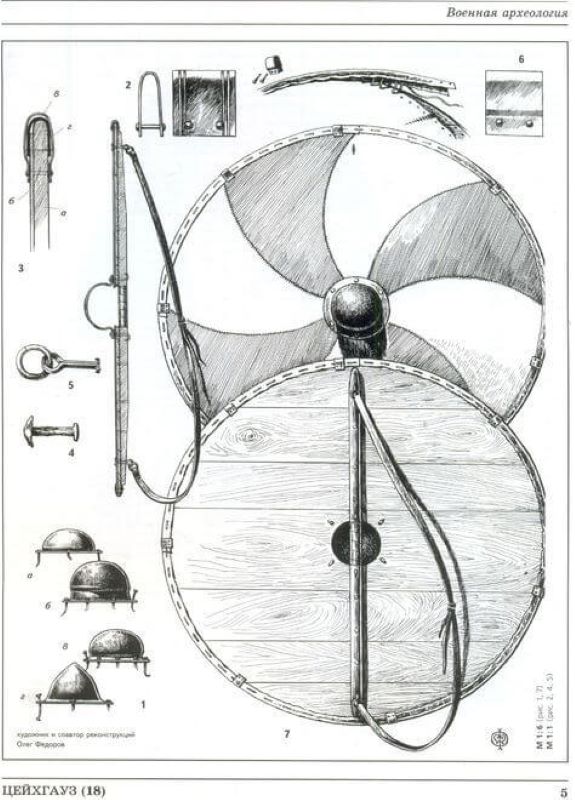

There are two main ways to hold a shield: center grip or straps.

Center Grip – The center grip, just as it sounds, has a center handle that the user holds with one hand. Some shields are domed or have an extending center boss that allows room for the hand. Others just have an extending handle.

The benefit of the center grip is the ability to move it anywhere it is needed, making it quick and nimble. The downside is that any impact to the shield is concentrated on the user’s wrist. This limits the amount of force the shield and its wielder can absorb or dish out.

Straps – For shields that were strapped to the arm, there was a leather strap that the user slipped their arm through and a handle that they gripped with their hand. The handle could be made from either leather, wood, or metal. There was a variation of this set up that used a belt known as a guige. The guige looped around the neck or shoulders, helping to support the weight. It also allowed the shield to be carried on the back or dropped and retrieved later. [1]

This configuration was more secure than the center grip and put the hand closer to the edge of the shield. This allowed the user to hold something in their left hand, such as reins or a dagger. Since the shield was more firmly secured to the body, the user could absorb and exert much more impact. The off-center configuration was also beneficial in shield formations and walls since the edge overlapped the shield to its right. The downside was the loss of agility in moving the shield to different locations since it was attached to the body.

Types of Shields

There are many types of shields from around the world and throughout history. Below I will be focusing on the most common medieval European shields.

One thing I will point out before I begin are the terms I’m using. Most of them are not from the period but assigned later by historians to differentiate between types of shields. Most shields used during the Middle Ages were just called “shield.”

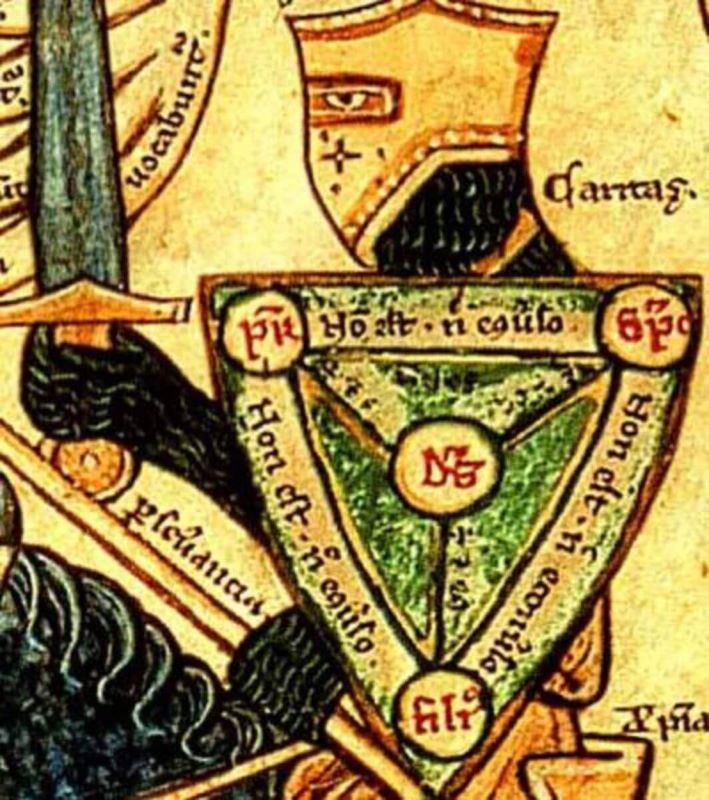

Heater Shield – This shield is probably the most iconic and the one most people think of when picturing a medieval shield with the flat top and pointed bottom. It was developed during the 12th century from the kite shield (more on that later). It commonly used straps. It was carried by every class of society and became the standard for displaying heraldry. It was on the smaller side and left the legs unprotected. It was named a heater shield by 19th century historians who thought it resembled the shape of an iron.

Kite Shield – Also known as a teardrop shield, the kite shield was large with a rounded top and a pointed bottom. It was developed to protect the entire body of a mounted rider. However, it was also used by foot soldiers because of the amount of protection it provided. It was used heavily by the Normans starting in the 11th century. [2] Straps and occasionally a guige were the most common ways of holding it.

Round Shield – This type is one of the oldest and simplest forms of the shield. It is closely associated with the Vikings, who commonly used this type of shield. It could have a center boss or not, and could either use a center grip or straps.

Tower Shield – The tower shield was not a commonly seen type of medieval shield but people during that period were aware of them. The most famous version of the tower shield was the Roman scuta, a center grip used by Rome legionnaires including in the testudo or tortoise formation.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2021 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Clements, John (1998). Medieval Swordsmanship: Illustrated Methods and Techniques. Boulder, Colorado: Paladin Press. ISBN 1-58160-004-6. [2] Oakeshott, Ewart (1997) [1960]. The Archaeology of Weapons: Arms and Armour from Prehistory to the Age of Chivalry. Mineola: Dover Publications. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-0812216202.

The Writer’s Guide to Victorian Clothing Myths

Posted on October 15, 2021 96 Comments

The corset tends to take the spotlight when it comes to misinformation about Victorian dress. But there are myths surrounding other articles of clothing that have been repeated in books, TV shows, and movies.

If you are interested in corset myths, I suggest reading my two articles here and here.

Hoop Skirts Were Solid

Hoop skirts, also known as crinolines or cage crinolines, were developed to replace the multiple layers of petticoats that were being used to achieve the fashionable wide skirt of the 1850s and 60s. They were made of a widening series of flexible wire hoops connected by vertical tapes suspended from the waistband. The hoops could be left bare or covered with fabric. This arrangement meant that hoops skirts could be squished into different shapes for passing through narrow spaces or sitting. When removed, they collapsed flat.

Unfortunately, several movies and TV shows depict them as been solid rigid structures with no give. For an idea of how flexible hoop skirts are I suggest watching this video by Prior Attire.

Clothing was Hot and Uncomfortable

One of the questions I get as a historical reenactor all the time is: Aren’t you hot? Of course, if the outside temperature is in the 90s or 100s °F (32-37° C) everyone is hot no matter what they are wearing. However, most of the time I’m comfortable because my entire outfit is made of natural breathable fabrics. Even if I’m wearing a corset, because it’s made of natural fibers, it’s usually not too bad. If I’m wearing a hoop skirt, I’m even more comfortable because I get the air flow under the skirt. Honestly, I’m probably cooler than the people wearing skin-hugging polyester.

It Took a Long Time to Get Dressed

There is a belief that historical clothing, especially that from the Victorian era, took a long time to get into. This is probably due to how complicated it looks. However, I can say from personal experience that getting dressed in full Victorian attire usually takes about 15-20 minutes. Honestly, it sometimes takes me longer to do my hair than it does to get dressed.

Also, contrary to popular belief, I can completely dress myself. It helps to have another person lace the corset, but I can do it on my own, if needed.

I recommend this video to see how long it takes to get into various women’s styles from the Victorian era.

Going to the Bathroom

Another question I get is: How do you go to the bathroom in that? I do it the way they did back then. I wear split bloomers, which are open at the crotch. Then I lift the skirt in the front and straddle. That way I don’t have to mess with lifting everything in the back, which would be especially difficult with the bustle styles. If a woman was using a chamber pot, she would just lift her skirt in the front and place it between her legs

People Were Much Smaller Back Then

People were slightly smaller during the Victorian era. However, they were not the midgets that people think of. The main reason we picture Victorians as tiny is because most of the clothing from the period that survives was worn by teenagers and women in their early 20s. This clothing made it for a couple of reasons. One, since only small young women could fit into it, it wasn’t worn until it fell apart. Two, many of these dresses were sentimental and expensive, such as wedding and court presentation gowns. Think about how many women today save their wedding dresses even though they can’t fit into them years later.

Most of the larger clothing was worn until it disintegrated, leaving us with mostly smaller examples.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2021 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

The Writer’s Guide to Corset Myths

Posted on October 8, 2021 19 Comments

Part 2

Today we are busting more corset myths.

If you want to read Part 1, please go here.

Passing Out

The image of the swooning lady is one of the most lasting of the Victorian era. Were some women passing out because they had laced down too severely? I’m sure there were. I personally have seen a woman pass out from being too tightly laced. However, there were a lot of other things going on to lead to swooning.

Gaslighting (using a gas flame as lighting, not the method of psychological manipulation) was first developed in the 1790s. [1] It became widespread in cities by the 1820s. Victorian homes often had small rooms and they rarely opened their windows. Being in a closed room with open gas flames would understandably lead to a shortness of breath.

Arsenic was commonly used during the 19th century to produce a popular green color for wallpaper and clothing. White arsenic was also used in makeup and skin whitening treatments. [2] One of the symptoms of arsenic poisoning is an abnormal heart rhythm and lung cancer can occur with long term exposure. [3]

Lastly, swooning was a common device used in literature of the period. Real life women began copying their literary counterparts and swooning to get attention or escape a distressing situation.

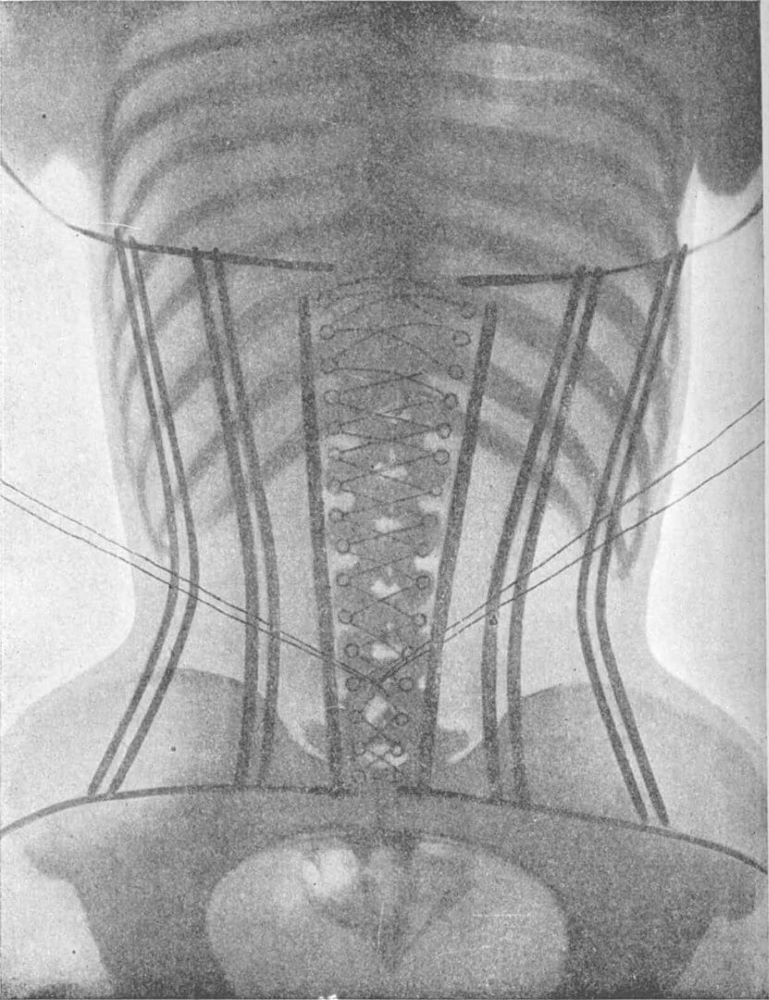

Moving Internal Organs

A corset can cause some shifting of internal organs and fat. However, when it is removed, the organs just go back to their normal positions, sort of like squishing a water balloon. Mainly, corsets lift the bust and squish the fat either down or up. It should also be kept in mind that internal organs are displaced during pregnancy, only to return to their original positions after birth.

When wearing a corset (or stays) there is some compression of the bottom of the ribs, making it harder to take a deep breath. However, you simply learn to breath more shallowly and in the top of your lungs. Honestly, after a few minutes of wearing a corset, I hardly notice I’m breathing differently.

Removing Ribs

There is no documented case that I know of a woman having ribs removed during the Victorian era. Considering the primitive state of medicine and anesthesia at the time it is unlikely a woman would voluntarily go under the knife to remove ribs.

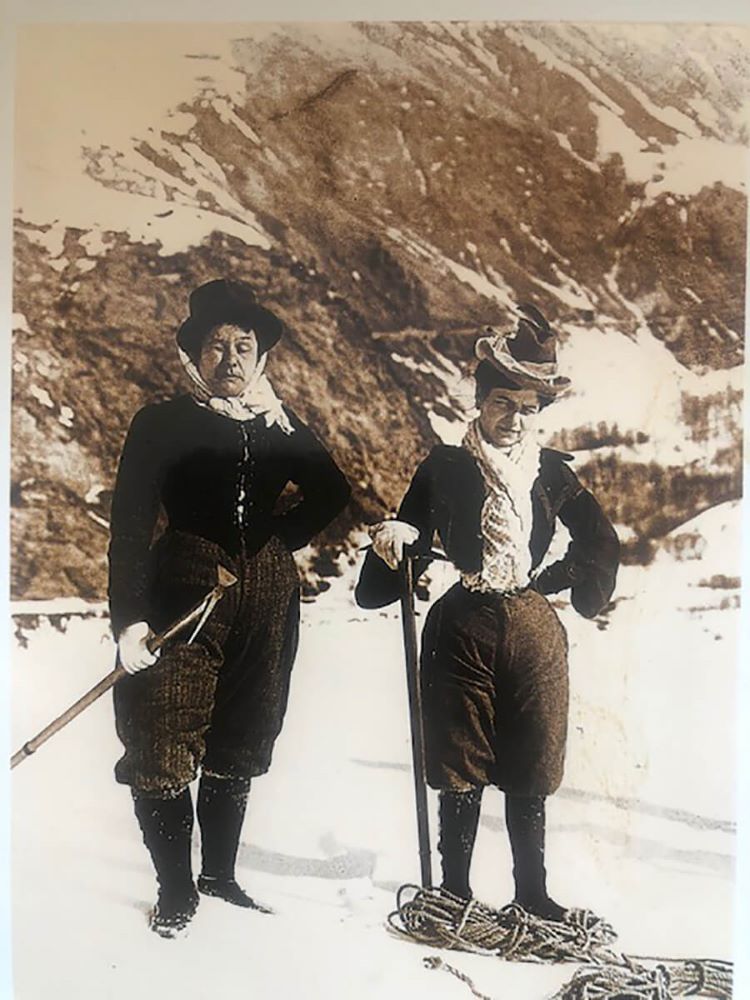

Inability to Move

I can confirm from practical experience, that a corset (or any other boned garment) doesn’t drastically affect movement. I have shot archery, ridden a horse, and fenced in a corset. There are many examples of women being active while wearing corsets, including this article of female mountain climbers.

Yes, there is some limiting of movement but not enough to prevent most activities. The biggest limitation is being unable to bend at the waist. But it’s easy enough just to bend at the hips instead.

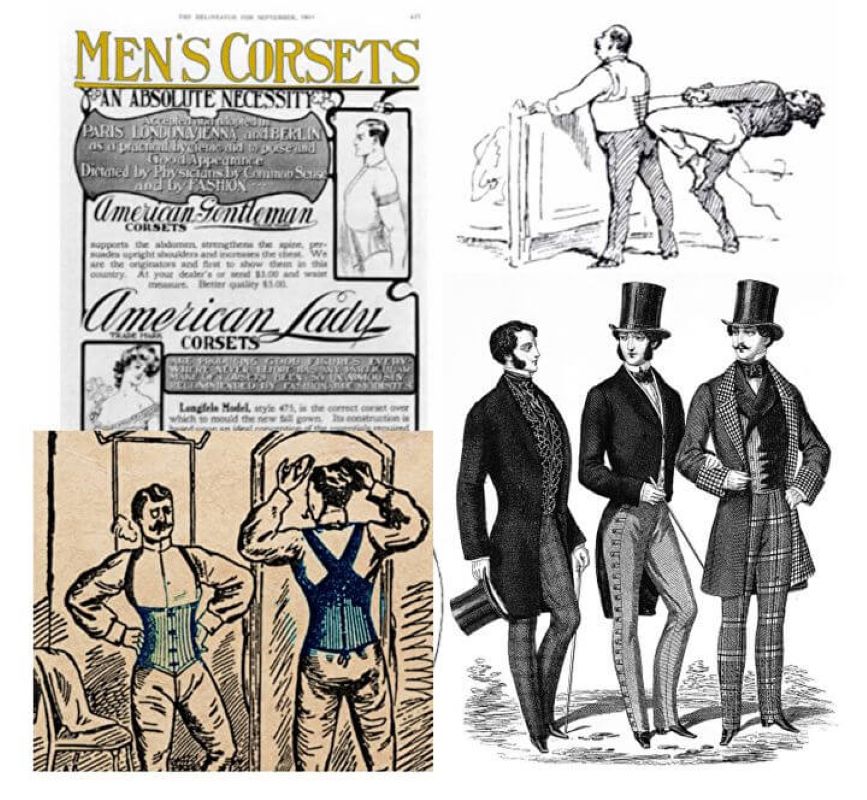

Male Corsetry

Men were not excluded from corsetry. Military officers during the Napoleonic War began discretely wearing boned waistcoats or other garments to achieve the flat-bellied look. During the 1820s and 1830s, the silhouette for men had a severely nipped in waist that pretty much demanded a corset to achieve.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2021 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Janet Thomson; The Scot Who Lit The World, The Story Of William Murdoch Inventor Of Gas Lighting; 2003; ISBN 0-9530013-2-6 [2] "Display Ad 48 – no Title". The Washington Post (1877–1922). 13 February 1898. [3] https://www.healthline.com/health/arsenic-poisoning#complications

The Writer’s Guide to Corset Myths

Posted on October 1, 2021 147 Comments

Part 1

When people find out I’m a historical reenactor and routinely wear a corset, I am asked several outlandish questions. Have I ever passed out? Have my organs moved? Isn’t that thing incredibly uncomfortable? I was told by a former coworker once that if anyone wears a corset, they will die.

Obviously, there are a lot of myths perpetuated about corsets and other boned garments like 18th century stays and 16th pairs of bodies. In this two-part article, we will be jumping into the most common myths.

If you want a brief history of boned garments, I recommend you read my Writer’s Guide to the History of Corsets.

I also recommend this video about corset myths.

The Purpose of Corsetry

There is this narrative out there that women were forced into a device of torture that was cranked down to achieve a twelve-inch waist (30.48 cms). First, many women throughout history voluntarily choose to wear a corset just as many women today freely chose to wear a bra. And let’s not forget the modern waist trainer that is basically a corset.

Second, the purpose of corsetry throughout most of its history was to smooth the figure and lift the bust. They also acted as a back brace for working women. During the 18th century, stays were used as a base to pin clothing to, such as stomachers.

Third, there is a big difference between tight lacing and wearing a corset as part of everyday clothing. I have put tight lacing into its own section, so more on that later.

Impossibly Tiny Waists

We might as well address the elephant in the room. Did all women from the 16th to the early 20th century lace down to extremely tiny waists? The short answer is no. I’m sure there were some women who went to extremes. In our modern world, there are people who are starving themselves or getting extensive plastic surgery. Is this minority indicative of what the rest of us are doing? Of course not! Yet these people tend to get outsized attention because their behavior and appearance is outrageous. The same was true of women who tight laced to extremes.

In fact, during the period there were concerns about lacing down too far and recommendations of sensible waist measurements. One example is this 1883 article from the Toronto Daily Mail that states that 25-27 inches (63.5-68.58 cms) not too large. In fact, the columnist says anyone that laces an unfortunate girl day and night down to 18 inches (45.72 cms) should be put in a straight waistcoat (i.e., a straitjacket). [1] For comparison, below is the size guide for Forever 21, an American brand marketed to younger women. As you can see, their XS and S sizes have a waist measurement range from 24-27 inches (60.96-68.58 cms).

Another reason we know not all women had tiny waists is because we have surviving garments with large waist measurements. [2] Yes, there are blouses from the 19th century in museums with small waists but most of them were made for teenagers or women in their early twenties.

Optical Illusion

The appearance of a tiny waist through much of history was achieved partially by optical illusion. If a woman is wearing a large puffy skirt, especially one supported by multiple petticoats or a cage crinoline (and multiple petticoats) with a bodice with a large fluffy bertha or wide sleeves then her waist will look small by comparison. Another thing to keep in mind is that padding was common. Women (and men) padded out their hips, butt, bust, and shoulders. The amount and location of padding depended on the time period and fashionable silhouette. A great modern example of this optical illusion is Lily James in Disney’s Cinderella.

Photo source.

Tight Lacing

Throughout much of history, eyelets for lacing were just holes bored through the fabric with an awl and reinforced with stitching. As a result, there was a limit on how tightly they could be laced. Cranking the lacing on thread eyelets will cause them to tear out. It wasn’t until the metal eyelet became widespread in the 1850s that tight lacing was even achievable. Even then, tight lacing was only practiced by a small minority of high fashion women.

Many of the photographs of Victorian women with impossibly tiny waists were altered. Photo shops routinely touched up photographs to not only make waists smaller but remove freckles, wrinkles, cleavage lines, and other imperfections. If you’re interested in a deeper dive into Victorian photoshop, I recommend this video by Bernadette Banner.

Worn Against the Skin

One of the biggest mistakes I see regarding boned garments in movies and TV is that they were worn directly on the skin. This is not true. Pairs of bodies, stays, and corsets were always worn over a chemise or shift. This prevented the body’s oils and sweat from damaging the corset and protected the wearer’s body from chafing. Also, the chemise could be laundered frequently while the corset could not.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2021 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=UP1MAAAAIBAJ&sjid=9jQDAAAAIBAJ&pg=4608%2C2577118 [2] Arnold, Janet. “Patterns of Fashion 2: Englishwomen’s Dresses & Their Construction C. 1860 - 1940”, 1982.

The Writer’s Guide to the History of Corsets & Other Boned Garments

Posted on September 24, 2021 20 Comments

There are few garments in human history that are surrounded by more myths and misinformation than corsets. Some wild claims have been made about the effects of corsetry and the reasons why women and men wore corsets. Today we will be diving into the history of boned and laced garments and over the next two weeks we will be busting myths.

I recommend this video from Abby Cox about the difference between pair of bodies, stays, and corsets.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

A Brief History

Women have been lacing themselves into various garments for roughly 500 years. There is even some evidence that Minoan women of early Crete were using a version of the corset. [1]

16th Century Pair of Bodies

The first boned and laced garment was the 16th century pair of bodies (also spelled bodys). [2] It spiral laced in the front or back through thread-enforced eyelets and had shoulder straps. The pair of bodies also had tabs at the bottom that fanned out over the hips and helped support the weight of the skirts and petticoats and prevented them from cutting into the flesh of the waist.It was used to create the conical torso that was fashionable at the time as well as to lift the breasts.

However, the idea of a woman lacing herself into a garment wasn’t new. The kirtles of the 15th century usually laced snugly and provided support for the bust. But the pair of bodies were the first to use boning. During this same period, lower class women began boning their bodices to provide lift to the bust and maintain a straight line. They also acted as a back brace for hard work. Reed and whalebone were used to provide structure. Neither of these materials is very stiff and over time they mold to the wearer’s body. [3] Some pairs of bodies had a pocket in the front for a busk, a piece of wood, horn, ivory, metal, or whalebone that insured the front remained straight.

18th Century Stays

During the 18th century, the pair of bodies transitioned into stays. [4] The shape changed but the basic function did not. Stomachers and other clothing were commonly pinned to them. Just as with the pair of bodies, the point was to create the fashionable conical silhouette. Plus, the shoulder straps pulled the shoulders back into the proper posture and the tabs supported the weight of the skirts and protected the waist. Unlike the pairs of bodies that were only worn by the upper class, stays were worn by all classes of women. It was considered improper to go without, sort of like going without a bra today.

The term “corset” was used during this period to describe an unboned support garment. Obviously, a lot of changes were made to get to what most modern people would recognize as a corset.

19th Century Corsets

Stays shortened to just below the bust during the beginning of the 19th with the high-waisted Empire styles. When the waistline began to drop again during the 1820’s, several changes were made, and this garment began to be referred to as a corset. Gussets for the bust and hips were added, and the shoulder straps became less common, disappearing by the 1840s. [5] Ironically, the corset was originally designed for men and favored by the dandy, but male corsetry is a topic for another post. [6]

The metal eyelet was first developed in 1828 although it wasn’t until Henry Bessemer developed a faster method in 1856 that they become more widely used. [7] It allowed corsets to really be cranked tight for the first time, a practice known as tight lacing. However, tight lacing was only practiced by a minority of high fashion ladies and was also an erotic fetish.

The other big change was the invention of the metal busk also known as front claps. The loop and post closure allow the corset to be opened and closed from the front with the lacing still in the back. This made it much easier to put on and take off.

The corset changed shape and length throughout the 19th century. Curved panels created a dramatic hourglass shape, even when the garment wasn’t being worn. With the introduction of metal boning and the invention of the steam heated torso at the end of the 1860s to shape the boning, even more drastic curves were achieved. [8] The hourglass shape was replaced in 1897 by the straight front or S bend corset, which pushed the bust forward and the hips back. [9]

Into the 20th Century

The corset continued into the beginning of the 19th century but by the 1920s it was being rapidly replaced by the girdle and the brassiere. Since then, corsets have seen brief periods of revival such as the waist cincher of the late 1940s and early 1950s and the corset fashions of the 1980s. It survives in a modified version today in the modern waist cinchers and shapewear as well as fetish wear and cosplay such as steampunk.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2021 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Steele, Valerie (2001). The Corset: A Cultural History. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09953-3. [2] Waugh, Norah (December 1, 1990). Corsets and Crinolines. Routledge. ISBN 0-87830-526-2. [3] Bendall, Sarah (2019-01-01). "Bodies or Stays? Underwear or Outerwear? Seventeenth-century Foundation Garments explained". Sarah A Bendall. Retrieved 2020-07-18. [4] Bendall, Sarah (2019-01-01). "Bodies or Stays? Underwear or Outerwear? Seventeenth-century Foundation Garments explained". Sarah A Bendall. Retrieved 2020-07-18. [5] Waugh, Norah (December 1, 1990). Corsets and Crinolines. Routledge. ISBN 0-87830-526-2. [6] Steele, Valerie (2001). The Corset: A Cultural History. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09953-3. [7] https://www.pinterest.com/pin/337277459563854497/ [8] "1860s corsets". vam.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2011-01-08. Retrieved 2010-06-20. [9] https://genealogylady.net/2015/08/16/fashion-moments-pigeon-breast/

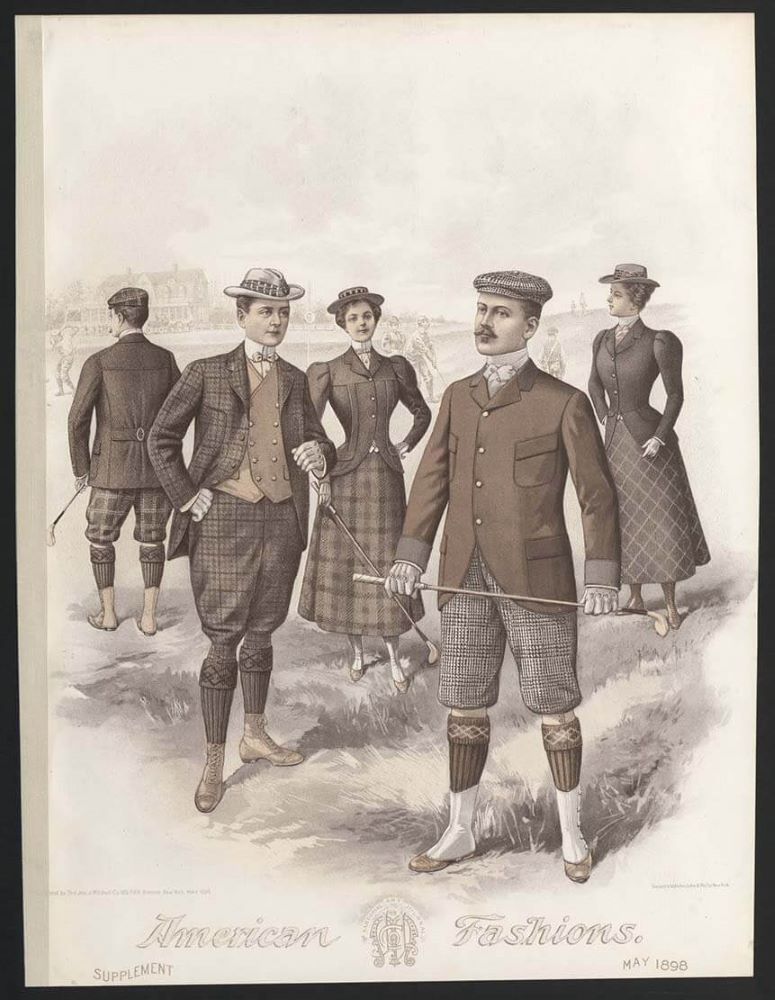

The Writer’s Guide to 1890s Men’s Fashion

Posted on September 17, 2021 108 Comments

Many of the trends from the 1880s continued into the 1890s. The trendy silhouette was slim. Fashions were becoming more informal and styles that were considered informal just a few decades prior were now appropriate for formal evening occasions or the professional office. Sportswear became important with the popularity of pastimes such as tennis, rowing, and especially bicycling.

For an overview of fashion for the entire 19th century, please read my Writer’s Guide to 19th Century Fashion. Another example of the clothing from this period is HBO’s “The Nevers.” Although it’s a fantasy show, the costuming is quite accurate.

Silhouette & Trends

A long lean silhouette was the fashion. Standing collars and tall crowned hats were seen in this decade in keeping with the slender look. However, the cut of trousers became more relaxed. [1]

Underwear

Shirts were commonly cotton and were heavily starched during this period. Collars were as high as three inches (7.62 cms) although they usually still featured turned down wingtips. [2] Shirt studs were a popular decoration. For informal events, striped or colorful shirts became popular. [3]

Readymade underwear was now available in department stores.

Daywear

The frock coat was still the most formal daytime option. However, the less formal morning coat was gradually replacing it. [4] The level of formality was determined mainly by the fabric used, ranging from formal dark colors to casual tweed. The morning coat suit was becoming the standard wear of businessmen. The lounge or sack coat was the most casual daytime option. It was a favorite of the working class although it was also gaining popularity with the upper class as a casual daytime alternative. [5] Three-piece or ditto suits made of the same fabric were common.

Waistcoats or vests, as the Americans called them, began to be made in colorful fabrics again. They were generally single breasted and could come with or without lapels.

Sportswear

Just like the ladies, sports were popular with men, and they had wardrobes to accommodate them. [6]

The reefer jacket without a waistcoat was worn at the seaside or for sporting. [7]

The Norfolk jacket was popular for shooting since its vertical pleats provided range of motion. It was commonly paired with breeches, called knickerbockers by the Americans, and boots or shoes with gaiters.

Lounge or sack suits made of light or striped fabric were popular choices for yachting, tennis, and the seaside. They were often paired with a straw boater hat. [8] A variation of the lounge jacket was the blazer, which was commonly made in navy blue, bold stripes, or bright colors, and was popular for sailing and the seaside.

The cycling craze was also enjoyed by men and any of the above options were acceptable. [9] If a Norfolk jacket and breeches were worn, it was usually with stockings and low shoes.

Eveningwear

A dark tailcoat paired with a white tie was still the standard for evening. The dinner jacket, known as the tuxedo by the Americans, was becoming an acceptable option for more informal evening affairs such as a dinner at home or an outing to the gentleman’s club. [10] It was a gussied-up version of the sack or lounge coat that had been introduced in the previous decade. [11}

Outerwear

Knee-length topcoats and calf-length overcoats were still common. They often had collars of fur or velvet.

Hairstyles & Headwear

Hair was short and usually parted to the side. Pointed beards and full moustaches were also popular.

The top hat was still necessary for formal affairs. The bowler was a popular informal option. The crown become rather tall. [12] The fedora was introduced during this decade. [13] It had a soft structure and a low creased crown. The prince of Wales, Edward VII, popularized a variation of the fedora known as a homburg. [14]

Footwear

Short ankle boots were the common shoe. The lower portion was usually leather with a contrasting cloth upper. They could be laced, buttoned, or secured by an elastic section on the side. A pointed toe became the fashion during this decade. Shoes normally came in brown or black although white was introduced in the 1890s for summer. Socks were black, even with white shoes. Sock suspenders, also known as shirt stays, were introduced during this decade and were elastic bands that clipped to the top of the sock and the bottom of the shirt.

Rubber and canvas shoes were worn for sports and were the ancestor of the modern sneaker.

Low laced pumps were the standard for evening. [15]

Accessories

Ascots or neckties done in a four-in-hand knot were the standard neckwear. They were usually secured with a stick pin. The bowtie returned to popularity during this decade.

Other popular accessories included the pocket watch, the cane, and cufflinks. Gloves were worn for daytime and evening although it was increasingly becoming acceptable to forego them.

Spats became a popular accessory during this decade.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2021 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Shrimpton, Jayne. Victorian Fashion. Oxford: Shire Publications, 2016 p. 38-40. [2] Tortora, Phyllis G. and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume, 5th ed. New York: Fairchild Books, 2010 p. 401. [3] Laver, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History, 5th ed. London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd, 2012 p. 206. [4] Tortora, Phyllis G. and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume, 5th ed. New York: Fairchild Books, 2010 p. 401. [5] Shrimpton, Jayne. Victorian Fashion. Oxford: Shire Publications, 2016 p 39. [6] Laver, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History, 5th ed. London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd, 2012 p. 202. [7] Laver, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History, 5th ed. London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd, 2012 p. 202. Shrimpton, Jayne. Victorian Fashion. Oxford: Shire Publications, 2016 p 40. [8] Shrimpton, Jayne. Victorian Fashion. Oxford: Shire Publications, 2016 p 40. [9] Laver, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History, 5th ed. London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd, 2012 p. 202-204. Tortora, Phyllis G. and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume, 5th ed. New York: Fairchild Books, 2010 p. 401. [10] Laver, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History, 5th ed. London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd, 2012 p. 205. [11] Tortora, Phyllis G. and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume, 5th ed. New York: Fairchild Books, 2010 p. 401-402. [12] Shrimpton, Jayne. Victorian Fashion. Oxford: Shire Publications, 2016 p 38-41. [13] Tortora, Phyllis G. and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume, 5th ed. New York: Fairchild Books, 2010 p. 403. [14] Hughes, Clair. Hats. London: Bloomsbury, 2017 p.44. [15] https://victorianweb.org/art/costume/nunn23.html