The Worldbuilder’s Toolkit: Oceans and Seas

Posted on March 13, 2026 Leave a Comment

Oceans and seas have long captured the human imagination. They are vast, unpredictable, and teeming with mystery, making them the perfect setting for fantasy and science fiction. Whether your story takes place on storm-tossed pirate ships, beneath alien waves, or on islands surrounded by endless sea, these watery realms offer endless possibilities for tension, wonder, and world-shaping lore.

In this guide, I’ll explore how to craft compelling oceanic settings, how seas influence civilizations and technology, and how to use them for plot, theme, and character development.

Understanding the Ocean as a Living World

Before you build a sea-based setting, decide what kind of ocean you’re working with.

Shallow vs. Deep Seas: Shallow coastal waters offer unique ecosystems, challenges, and visuals than vast, open oceans or deep trenches.

Calm vs. Violent Waters: Are the seas navigable, or are they home to raging storms, magical maelstroms, or gravitational rifts?

Saltwater vs. Alien or Magical Seas: Think beyond Earth. Seas of acid, clouds, liquid methane, or magical currents can reshape everything from ecosystems to trade routes.

Consider:

Currents, tides, and dangerous weather patterns

The presence (or absence) of islands, archipelagos, or floating cities

Native marine life. Realistic, mythological, or completely invented?

Hidden realms below the surface: ancient ruins, alien habitats, or living coral empires

Sea-Based Civilizations: Shaped by the Waters

People who live by or on the sea develop to meet its challenges. Maritime cultures may revolve around trade, navigation, sea gods, or survival.

Coastal Empires and Seafaring Nations

Economies depend on fishing, trade, piracy, or resource extraction (e.g., pearls, magical kelp, deep-sea mining). Architecture must withstand wind, salt, and waves. Harbors, piers, canals, and stilt-houses shape daily life. Social structures may revolve around seafaring guilds, naval power, or religious orders devoted to ocean spirits or deities.

Island Cultures

Resources are limited; ingenuity and adaptation are key. Expect strong oral traditions, tight-knit communities, and deep respect for nature. Navigation has become a sacred science. Elders may memorize currents, stars, and migration patterns as part of their cultural legacy. Isolation might preserve unique traditions or make them vulnerable to colonization, invasion, or extinction.

Underwater Civilizations

These might be alien, magical, or transhuman. Consider how underwater physics shape everything from communication to warfare. Cities may be inside domes, grown from coral, or formed in geothermal vents. Societies may have caste systems tied to depth tolerance or bioluminescent markings.

Character Idea: A priest-astronomer of a tide-worshiping coastal people discovers that the moon’s cycle is changing and with it, their future. She must voyage across dangerous seas to uncover the truth.

Ocean Travel and Trade: Routes, Risks, and Rewards

Waterways shape economies and political alliances in powerful ways.

Trade and Exploration

Shipping lanes have become vital arteries for food, wealth, and culture. Control of straits or sea gates may spark a war. Explorers charting the “edge of the world” may find lost continents, floating kingdoms, or tears in reality. Sea charts, tide lore, and magical compasses can be major plot elements.

Piracy and Naval Warfare

Piracy may be a noble rebellion or ruthless terror. Sea bandits, ghost ships, or rebel fleets could serve as protagonists or threats. Naval empires require shipbuilding, cannon tech (or magical equivalents), and command structures. Consider how sea battles differ from land battles . Submarine warfare in a sci-fi setting might use stealth drones, sonar disruption, or alien marine beasts.

Hazards of the Sea

Storms, whirlpools, magical fogs, krakens, sirens, or sea mines. All significant obstacles for tension and plot complications. Long voyages may lead to scurvy, dehydration, mutiny, or cabin fever. Sci-fi dangers such as rogue waves on terraformed planets, sea-borne diseases, or sentient weather systems.

Example: In Treasure Planet, a sci-fi adaptation of Treasure Island, solar-sailing ships navigate the ether like ocean-faring vessels, fusing classical naval tropes with futuristic flair.

Myth and Mystery: The Sea as Legend

The ocean is a natural setting for myth – its depths unknown, its horizons endless.

Legendary Creatures and Beings

Create your own versions of sea monsters, merfolk, leviathans, or god-like beings slumbering in the trenches. Consider ecosystems where smaller predators swarm in deadly schools or where one colossal creature acts as a living island.

Sunken Ruins and Lost Cities

Atlantis-like ruins can hold ancient secrets, magical tech, or cursed relics. Your characters might be salvagers, scholars, or guardians trying to protect or exploit these places.

Religious or Superstitious Beliefs

Fisherfolk may believe in appeasing sea spirits before setting sail. They might interpret storms as divine punishment or messages from the deep. In a sci-fi world, cults may form around ancient alien signals coming from the ocean floor.

Character Idea: A deep-sea diver with enhanced lungs hears songs no one else can. She’s lured deeper, unsure whether it’s madness or a siren’s call to destiny.

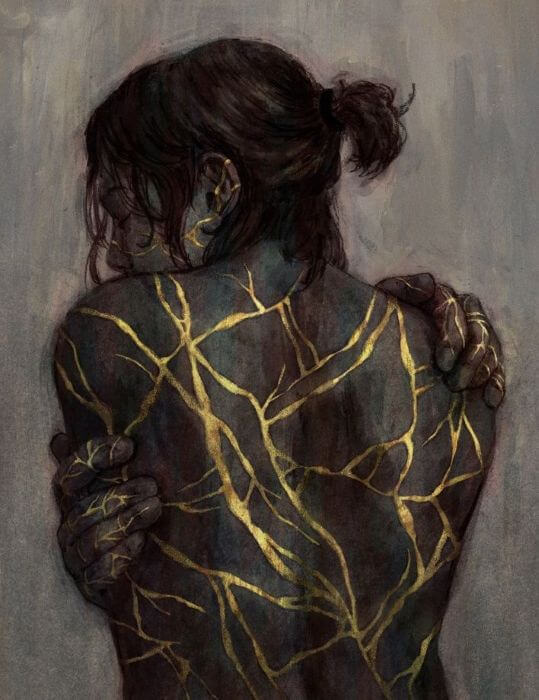

Oceans as Thematic Metaphor

Beyond the physical setting, oceans can serve symbolic purposes.

The Unknown: Oceans symbolize mystery, fear, and the vastness of what we don’t understand, perfect for quests or coming-of-age arcs.

Transformation: Water often symbolizes rebirth. Characters may undergo personal evolution tied to a voyage, shipwreck, or plunge into the deep.

Isolation: Characters lost at sea (literally or metaphorically) can experience powerful themes of loneliness, survival, and self-discovery.

Alien or Magical Oceans: Beyond Earthly Waters

Let your imagination drift beyond blue water and coral reefs.

A floating ocean planet with no land, where civilizations live on massive drifting cities or the backs of mega-fauna.

A dead sea, where no life remains except psychic jellyfish that communicate through dreams.

A world where the ocean is sentient, manipulating tides to protect or punish civilizations that worship (or exploit) it.

Inland seas of sand, or liquefied stone, blurring the lines between desert and ocean.

Example: In The Broken Earth trilogy by N. K. Jemisin, a distant ocean hides something ancient and powerful, with seismic implications. The sea is not just a setting; it’s a mystery the characters must solve.

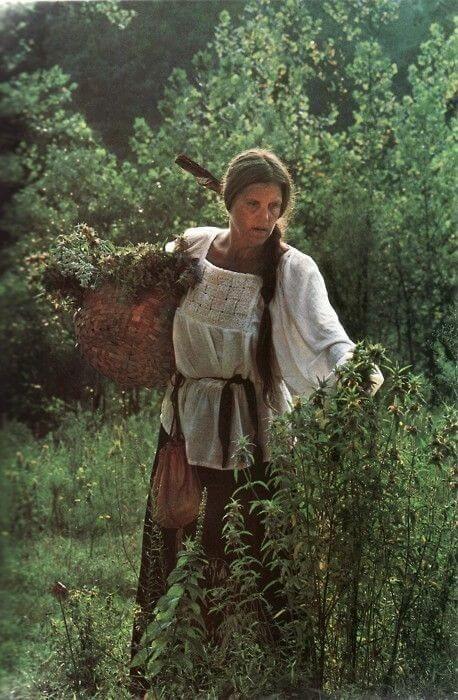

Real-Life Maritime Cultures as Inspiration for Fictional Worlds

Throughout history, civilizations living on coasts and islands or entirely dependent on the sea have developed complex relationships with the ocean. Their innovations, myths, and survival strategies provide rich inspiration for crafting fictional sea-based societies and characters. Here are several real-world maritime cultures and how they can inspire fantasy or science fiction world-building.

The Polynesians (Pacific Ocean)

Among the greatest navigators in history, Polynesian seafarers traveled thousands of miles using only the stars, wave patterns, and bird behavior. Their society was deeply connected to the ocean spiritually and practically, with sophisticated canoe-building and oral traditions.

Inspiration for Fiction

Culture: A star-navigating society that views ocean travel as a sacred duty. They pass navigation down orally, and they view the sea as a living ancestor.

Character Idea: A young navigator who’s forbidden from sailing after a prophetic dream. When their homeland faces ruin, they risk exile to chart a course into uncharted waters where gods are rumored to slumber.

The Vikings (North Atlantic and North Sea)

Norse seafarers known for their longships, raids, and trade across Europe and beyond. Vikings were explorers, warriors, and settlers, navigating harsh northern waters with speed and precision.

Inspiration for Fiction

Culture: A cold-sea civilization that reveres the storm as both a trial and a teacher. Sailors wear tide-blessed pendants before battle, and they enchant their longships with runes.

Character Idea: A cursed raider who hears the ocean whispering in their mind. They must lead their crew across a haunted sea, unsure if the voices are madness or the gods guiding them.

The Minoans (Aegean Sea)

An advanced Bronze Age civilization from Crete, heavily reliant on seafaring and trade. The Minoans built sprawling palace complexes, worshipped nature deities, and created rich artwork reflecting marine life.

Inspiration for Fiction

Culture: A matriarchal island society that lives in harmony with the sea, constructing coral-temples and bio-luminescent mosaics. Priestesses who read the tides and volcanic vents guide their fleets.

Character Idea: A novice tide-reader sees a pattern in the waves that matches an ancient prophecy, one that predicts the return of a long-drowned god.

The Swahili Coast (East Africa)

The Swahili city-states were prosperous trading ports along the East African coast, influenced by Arab, Persian, Indian, and African cultures. Their ships (dhows) connected them to distant markets, and their culture was rich in art, poetry, and architecture.

Inspiration for Fiction

Culture: A multicultural port city at the crossroads of magical continents, where sea-caravans carry not only goods but ancient songs and curses. Architecture blends coral stone and cloud-glass.

Character Idea: A multilingual dockmaster turned reluctant diplomat when tensions rise between oceanic traders and land-empire ambassadors. She must navigate shifting political tides while unraveling the truth behind a sunken cargo rumored to hold a god’s breath.

The Bajau (Southeast Asia)

Known as “Sea Nomads,” the Bajau people of Southeast Asia have traditionally lived most of their lives on boats, diving without modern equipment and spending extended periods underwater.

Inspiration for Fiction

Culture: An aquatic-adapted people who live on floating cities and underwater caves, using gill-tech or innate lung control. Their warriors ride manta-beasts and speak in pressure-coded clicks.

Character Idea: A storm that sank part of their flotilla caused people to blame a sea-born hunter with extraordinary breath control. To prove their innocence, they must dive into the Abyss Trench, a place from which no one has returned.

The Phoenicians (Mediterranean Sea)

Masters of ancient maritime trade, the Phoenicians established colonies and routes across the Mediterranean. They were expert shipbuilders and are credited with spreading written language.

Inspiration for Fiction

Culture: A mercantile sea-empire known for “living ships” – vessels grown from reefwood and infused with minor spirits. Every merchant captain is also a bard, trained in negotiation and song-magic.

Character Idea: A traveling scribe who discovers a lost Phoenician-like tongue embedded in sea chants. Deciphering it unlocks not only a map to a forgotten isle, but control over the tides themselves.

The Haida and Tlingit (Pacific Northwest)

Coastal Indigenous peoples known for their expert seafaring canoes, intricate art, and oral histories. Their relationship to the sea is deeply spiritual, with clan totems often tied to marine animals.

Inspiration for Fiction

Culture: A cold-sea culture where each clan bears a bond with a specific marine spirit, passed down in story, song, and carved talismans. War can only be declared with the breaking of a driftwood totem.

Character Idea: A clan-less orphan carves a totem of an unknown sea-creature that begins showing up in the real world. Some see it as a sign of war. Others, of rebirth.

Tips for Using Real Cultures as Inspiration Respectfully

Blend, Don’t Copy: Avoid one-to-one analogues. Use real-world elements as a launching point, then layer your own geography, language, and technology.

Honor Depth: Dig beyond aesthetics. Research the culture’s worldview, social structure, and relationship with nature or the sea.

Avoid Stereotypes: Steer clear of eroticizing or romanticizing. Respect the nuances and dignity of the original culture.

Use Sensitivity Readers: If your story closely resembles a specific culture, a sensitivity reader can help ensure accuracy and respect.

Vast Waters and the Impact on Travel and Trade

Oceans and seas have long served as both highways and hazards. In speculative fiction, these vast waterways can shape entire economies, determine political power, and challenge adventurers at every turn.

Trade Routes and Economic Power

Sea Routes as Lifelines: In most ocean-based or island-heavy worlds, trade by ship is more efficient than land travel. Coastal cities and island ports become economic hubs, cultural melting pots, or diplomatic flashpoints.

Strategic Choke Points: Control of narrow straits, canals, or enchanted reefs can grant vast political power. Wars may erupt over who controls the passage of goods (or the rare leviathan bones that fuel magic).

Trade Goods: Oceans provide fish, salt, coral, rare herbs, sea silk, magical bioluminescent algae, and more. Underwater mining colonies may harvest crystals or alien tech buried in trenches.

Piracy and Naval Control: Trade also draws threats: pirates, sea monsters, and rogue navies. This creates a constant push-and-pull between law, chaos, and those who profit from both.

Travel and Exploration

Navigation: In fantasy, sea travel might involve magic compasses, star readers, or aquatic familiars. In sci-fi, navigation could require interstellar drift mapping, wormhole-tide charts, or AI ocean-current prediction.

Ship Types: Different waters require different vessels. Sleek catamarans for calm seas, heavily armored dreadnoughts for hostile alien waters, flying ships for wind-based magic systems.

The Unknown: The ocean represents the unexplored. Maps end with warnings: “Here Be Monsters.” Your characters may face whirlpools, magnetic storms, or seafloor gates that open to other worlds.

Character Impact

Mariners and Traders: Characters who rely on the sea may be shaped by its danger and unpredictability, pragmatic, weather-worn, superstitious, or adventurous.

Explorers: A protagonist might be the first to cross a forbidden sea, driven by legend, duty, or exile. Their journey could shift the balance of power or uncover long-lost civilizations.

Ship-Bound Societies: Entire cultures could live on the water: on ships, barges, or floating cities. These groups may not understand land ownership and treat the sea as sacred.

Example: In One Piece, the Grand Line is both a deadly travel route and a global trade corridor. Its constant weather shifts, strange islands, and sea beasts make it as much a character as any of the protagonists.

Oceans as Realms of Myth, Legend, and Hidden Mystery

Oceans are rich with symbolism, frequently seen as birthplaces of life, gateways to the unknown, and homes of the divine or monstrous. In both fantasy and science fiction, the sea is a perfect setting for myths and secrets that lurk just out of reach.

The Sea in Myth and Symbolism

Creation Myths: Many cultures envision the world emerging from oceanic chaos or being shaped by sea gods. Your world might have a literal Sea of Origins or a sunken divine body from which life sprang.

Gods and Spirits: Storm gods, tide spirits, and sea monsters are recurring motifs. In your setting, gods may sleep beneath the waves, stirred only by blood or betrayal.

Legendary Locations: Atlantis, Lemuria, Ys, and sunken cities echo across myth. You can create your own sunken empires, floating islands, cursed reefs, or oceans that remember forgotten things.

Mysterious Depths and the Unknown

What Lies Beneath: The deep sea remains one of the least explored regions of Earth. In your story, it might hold: buried civilizations (pre-cataclysmic empires or alien colonies), elder beings (gods or monsters sealed away), forbidden tech (a crashed ship, a sealed AI, a vault of pre-magic knowledge), or organic intelligence (a sentient coral reef, or oceans that think)

The Deep Changes You: Pressure, darkness, isolation. Characters descending into the abyss may not return unchanged – physically, mentally, or spiritually.

Recurring Ocean Myths and Tropes to Reimagine

Sirens: Lure sailors with beauty, music, or memory. In sci-fi, they could be psychic aliens or data-ghosts from sunken shipwrecks.

Ghost Ships: Abandoned vessels haunted by lost crews or acting with strange intelligence. Perhaps the ship sails itself, carrying a prophecy.

Sea Curses: Taboos broken at sea can have long-lasting consequences: drought, famine, haunted weather. A fisherman may awaken something ancient with a forbidden catch.

Character Idea: A sailor marked by the sea (tattoos that change with the tides) dreams of an underwater city she’s never seen. When she sails beyond the last charted island, the sea speaks.

Example: In The Odyssey, the sea is both pathway and punishment, with monsters, storms, and gods controlling Odysseus’s fate. In The Abyss (film), the ocean becomes a mirror of human fear and a place where other intelligence hides in plain sight.

Plot and Character Ideas

The Leviathan Treaty

Genres: Epic Fantasy, Political Intrigue

Plot Idea: A deep-sea leviathan has awoken for the first time in centuries and demands renegotiation of a forgotten pact that protects coastal cities from destruction.

Character Angle: A low-ranking diplomat fluent in ancient sea-tongue is thrust into negotiations with the creature and must uncover what caused the original pact to fray.

Twist(s): The leviathan isn’t the original; it’s a younger sibling avenging a broken peace, and the cities may have committed atrocities long buried beneath the waves.

Ghostwake

Genres: Sci-Fi Horror, Mystery

Plot Idea: A research submarine receives a distress signal from a vessel that vanished 40 years ago in the deep ocean trench “Ghostwake.”

Character Angle: A grieving ex-naval officer joins the recovery team, hoping to find answers about her lost sibling, who was aboard the original vessel.

Twist(s): The missing crew is alive, preserved by a non-linear time anomaly, trapped in an endless loop unless someone breaks the cycle.

Siren’s Anchor

Genres: Fantasy Romance, Dark Fairy Tale

Plot Idea: A siren bound by a curse to one island falls in love with a sailor who visits every year, but she can never leave, and he can never stay.

Character Angle: A cursed immortal, the siren dreams of freedom more than love, but fears losing the only soul who sees her as more than a monster.

Twist(s): The sailor is aging backward, cursed himself, and their last meeting may be his first or final.

The Deep Parliament

Genres: Sci-Fantasy, Political Thriller

Plot Idea: Representatives of surface nations are invited to a mysterious summit hosted by the Deep Parliament, an underwater alliance emerging after millennia of silence.

Character Angle: A jaded human diplomat with a scandalous past is sent to the summit as punishment but discovers political intrigue among the sea-folk that could change everything.

Twist(s): The Parliament is debating whether the surface deserves access to deep-sea energy sources or eradication to prevent further ecological collapse.

Saltwitch

Genres: Dark Fantasy, Coming-of-Age

Plot Idea: A coastal village trains one girl per generation as a Saltwitch to appease the sea spirits. The current candidate refuses.

Character Angle: A rebellious teenage girl uncovers the truth: the Saltwitch isn’t a sacrifice, it’s a guardian. And the next tide brings a threat only she can face.

Twist(s): Interdimensional beings known as “spirits” inhabit a realm connected to the ocean floor, and they are waking up angry.

The Coral Citadel

Genres: Fantasy Adventure, Lost Civilization

Plot Idea: Explorers seek the mythical Coral Citadel, said to appear only during certain celestial alignments deep in the southern sea.

Character Angle: A cartographer’s apprentice with perfect memory is brought along for their mind, not their bravery. But their visions may be the key to unlocking the citadel’s secrets.

Twist(s): The citadel is alive. Its architecture shifts with tides and thought, and it’s selecting a new ruler from among the intruders.

Tideglass

Genres: Urban Fantasy, Mystery

Plot Idea: People along a seaside town go missing, and tidepools are found reflecting places that don’t exist.

Character Angle: A skeptical local diver finds a shard of tideglass that shows glimpses of a mirror world beneath the sea, one where the missing might still be alive.

Twist(s): The reflections aren’t illusions, they’re invitations. But the underwater realm has its own price for entry.

Blue Harvest

Genres: Sci-Fi Thriller, Ecofiction

Plot Idea: A corporate ocean farm harvesting bio-engineered plankton loses contact with its sea-based workers.

Character Angle: A retired biologist returns to the industry she helped create to investigate, haunted by earlier ethical compromises.

Twist(s): The genetically modified plankton has developed sentience and may be forming a hive-mind in the currents.

The Navigator’s Bones

Genres: Nautical Horror, Fantasy

Plot Idea: A legendary shipwreck reappears once every generation. It’s said that whoever claims the Navigator’s Bones gains mastery over the tides.

Character Angle: A reluctant descendant of the ship’s captain is blackmailed into joining a scavenger crew, drawn into their ancestor’s unfinished voyage.

Twist(s): The ship isn’t a ruin. It’s a trap, rebuilding itself from the bones of those who come seeking it.

Beneath the Shellsky

Genres: Science Fantasy, Exploration

Plot Idea: On a waterworld with a reflective, opaque shell-sky, navigators must learn to read the surface’s mirrored stars to explore the planet.

Character Angle: A blind astromancer from an island observatory is the only one who can interpret the shellsky and may hold the key to what lies beyond it.

Twist(s): The shellsky is not atmospheric; it’s the inside of a living organism, and someone is trying to wake it.

Whale-Rider of the Storm Shoals

Genres: Heroic Fantasy, Mythic Adventure

Plot Idea: Once a generation, a great storm whale rises from the depths and chooses a rider to restore a balance between sea and sky.

Character Angle: A shipwrecked orphan raised on a floating junktown is chosen, despite being land-born and forbidden.

Twist(s): The whale is dying, the balance is already lost, and the true task is to carry its last memories to the sea gods.

The Forgotten Tide

Genres: Time Travel, Magical Realism

Plot Idea: A reclusive lighthouse keeper starts seeing ghost ships on the horizon then realizes they’re not ghosts, but vessels from the past caught in a temporal tide.

Character Angle: A war veteran running from his past discovers he’s uniquely attuned to these tides and may be able to rewrite a key moment in history.

Twist(s): Changing the past may prevent a war but will erase the people he’s come to care about in the present.

Oceans and seas are more than just blue backdrops. They are rich, living landscapes that challenge your characters, shape your civilizations, and hold the power to transform your plot in profound ways. Whether your story sails across sci-fi currents or fantasy tides, crafting a well-developed marine world can immerse readers in the raw beauty, danger, and awe of the deep.

So dive in. The sea is waiting. Happy worldbuilding!

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

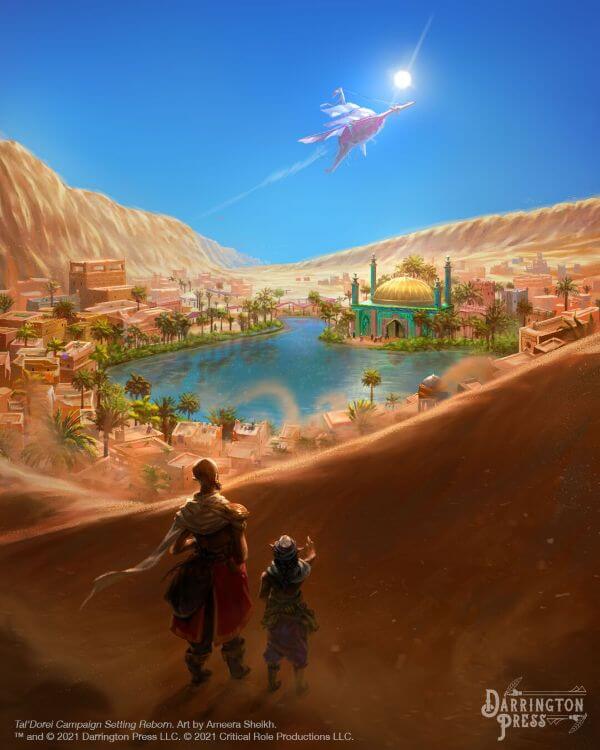

The Worldbuilder’s Toolkit: Deserts

Posted on February 27, 2026 Leave a Comment

Deserts may seem lifeless at a glance, but they pulse with stories waiting to be told. These harsh, arid landscapes are more than just stretches of sand or cracked earth. They’re crucibles that shape resilient cultures, drive innovation, and influence every aspect of survival. Whether you’re building a vast sci-fi world or a mythic fantasy realm, deserts can offer an evocative and immersive setting full of drama, danger, and depth.

In this article, I’ll explore how to craft believable and compelling desert settings, the cultures that thrive within them, and the role deserts can play in trade, conflict, and plot development.

Understanding the Desert Landscape

All deserts are not the same. Before diving into culture and plot, decide what kind of desert you’re building.

Sandy Deserts (ergs): Vast seas of shifting dunes, such as the Sahara.

Rocky or Stony Deserts (regs): Wind-blasted plains of gravel and rock.

Salt Flats: Crusty, shimmering expanses where water once existed.

Cold Deserts: Found at high altitudes or latitudes (e.g., the Gobi or Antarctica), where water is scarce, but temperatures can plummet.

Key Environmental Features

Extreme temperatures: Blistering heat by day, freezing cold at night.

Scarcity of water: Every drop is precious, affecting everything from the economy to religion.

Unpredictable storms: Sandstorms or electrical activity can be sudden and deadly.

Isolated oases: Natural watering holes often become centers of culture, trade, or power.

Deserts are not empty. Wildlife, hardy vegetation, and even thriving ecosystems exist, adapted to brutal conditions. Consider your world’s equivalent. Will the flora and fauna be familiar, or alien and dangerous?

Cultures Shaped by the Desert

People who live in the desert must adapt or perish. This shapes not only their technologies and economies but also their values, traditions, and social structures.

Survival-Based Innovation

Water collection and storage: From qanats (underground aqueducts) to dew harvesters, desert cultures innovate to trap and conserve water. In a sci-fi setting, this might include solar condensers or moisture farms.

Clothing and architecture: Expect loose, breathable clothing, often in light colors. People might build buildings from mud-brick or sun-bleached stone, with thick walls and small windows to insulate them from heat.

Mobility: Nomadic groups often dominate desert travel, using camels, sand skiffs, or advanced hovercrafts. Knowledge of terrain, stars, and weather is essential and often revered.

Cultural Impacts

Honor and hospitality: In many real-world desert cultures, hospitality is a sacred duty. Sharing water, food, and shade could mean the difference between life and death.

Spirituality and belief systems: Deserts can feel like places of divine silence or powerful spirits. Characters may worship sun gods, sky beings, or ancestor spirits said to ride the sandstorms.

Storytelling traditions: Oral histories flourish in cultures with limited written resources. Myths may center on survival, sacrifice, or transformation through the elements.

Example: Dune by Frank Herbert features the Fremen, a desert people with a deep, spiritual relationship to water and the land. Their entire culture – language, technology, clothing, even warfare – revolves around survival and desert ecology.

Desert Trade and Power

Though harsh, deserts are often vital to trade and politics.

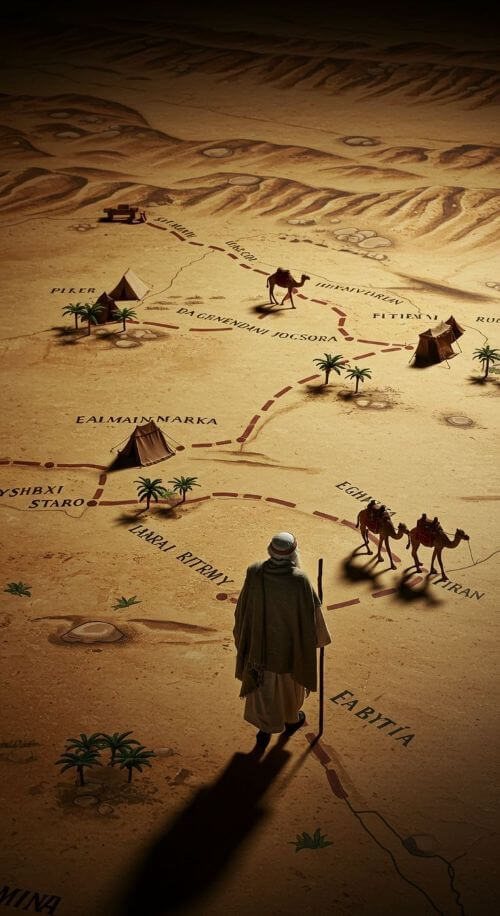

Trade Routes and Caravans

Deserts frequently connect powerful empires or resources (like spices, minerals, or rare magical components). Caravans and convoy networks create interdependence between cities, often controlled by guilds, tribes, or merchant families. Banditry and piracy thrive along lonely stretches. Your characters may guard, attack, or lead these caravans.

Oasis Cities and Trade Hubs

Cities built around oases become power centers, economically, politically, and spiritually. These hubs may host bustling bazaars, underground aquifers, and tightly packed architecture. Alliances and rivalries might revolve around control of wells, springs, or buried aqueducts.

Resource Wars

Water, shade, and rare materials like magical crystals or advanced tech minerals can become the basis for conflict. People might fight entire wars to control a single spring or trade pass. Empires may employ desert tribes as mercenaries or attempt to eradicate them to dominate the terrain.

Example: Mad Max: Fury Road showcases a post-apocalyptic desert wasteland where control of water (“Aqua Cola”) is central to power. The desert becomes both a battlefield and a metaphor for resource greed.

Designing Alien or Magical Deserts

In science fiction and fantasy, deserts don’t need to obey Earth’s rules. You can take the core concepts – scarcity, harshness, isolation- and amplify it.

Magic-infused sand that reacts to moonlight, causing illusions or dangerous mirages.

Living dunes that shift with awareness and trap travelers.

Creatures that burrow into space-time, surfacing only during solar flares.

A desert on a dying planet, where the atmosphere is toxic and the wind cuts like glass.

These ideas open wild possibilities for world-building while still capturing the thematic essence of deserts: survival, danger, and transformation.

Example: Stargate SG-1 often places its alien civilizations in desert environments that blend ancient aesthetics with advanced tech, drawing clear inspiration from Earth’s desert cultures while imagining their evolution in alien contexts.

Deserts as Metaphor and Theme

Deserts can be more than setting. They can be symbolic.

Isolation and introspection: A character wandering the desert may face inner transformation, mirroring the barrenness and clarity of the environment.

Trial and rebirth: The harshness of the desert strips away weakness, revealing what a character is truly made of.

Spiritual purification: The desert becomes a liminal space where characters encounter the divine, the monstrous, or their truest selves.

Real-Life Desert Cultures as Inspiration for Fictional Worlds

Real-world desert cultures offer a wealth of inspiration for writers crafting fictional societies. Shaped by extreme environments, these communities developed remarkable innovations, belief systems, and social structures that allowed them to thrive where life seems impossible. Whether you’re writing high fantasy or far-future sci-fi, drawing from these cultures can help you build civilizations that feel grounded, complex, and interesting.

Here are several desert-dwelling cultures and ideas on how to adapt them into fictional settings and characters.

Bedouin Tribes (Arabian and Syrian Deserts)

Overview: Nomadic herders and traders who traditionally traveled across the deserts of the Middle East, the Bedouin possess strong clan loyalty, excel in oral storytelling, practice hospitality customs, and demonstrate expert knowledge of the land.

Inspiration for Fiction: A nomadic people with deep spiritual ties to the stars and wind, traveling in caravans with solar sails or animal-like biomechs. Their survival depends on moving between shifting oases or ancient waystations marked by sacred stones.

Character Idea: A desert scout trained from childhood to read the dunes and stars. Fiercely loyal to their clan but questioning their people’s refusal to settle. Their journey could involve leading outsiders through sacred lands or uncovering a forgotten prophecy hidden in tribal stories.

Tuareg People (Sahara Desert)

Overview: A Berber-speaking, traditionally nomadic people known as the “blue people” because of their indigo-dyed garments. The Tuareg have a matrilineal society, distinct social customs, and control key trans-Saharan trade routes.

Inspiration for Fiction: A matrilineal desert culture that guards a legendary trade route through cursed lands. Their oral poets carry history in song, and only certain priestesses know the true map of the shifting sands.

Character Idea: A young courier of noble blood, entrusted with a secret cargo and an ancient song that may hold the key to survival for her people. She faces a moral dilemma between protecting her clan and ending a centuries-old conflict fueled by trade monopolies.

San People (Kalahari Desert)

Overview: One of the oldest continuous cultures on Earth, the San have gained recognition for their hunter-gatherer lifestyle, detailed knowledge of tracking and animal behavior, and a rich tradition of storytelling, cave art, and spiritual beliefs.

Inspiration for Fiction: A small desert community that speaks through symbols and glyphs, leaving prophetic markings on sacred canyon walls. Their survival depends on tracking elusive desert beasts that hold magical properties.

Character Idea: A dreamwalker who enters trance states to commune with ancestral spirits and interpret the signs left in ancient cave art. Their visions become more vivid and more dangerous as a mysterious drought stretches into its third year.

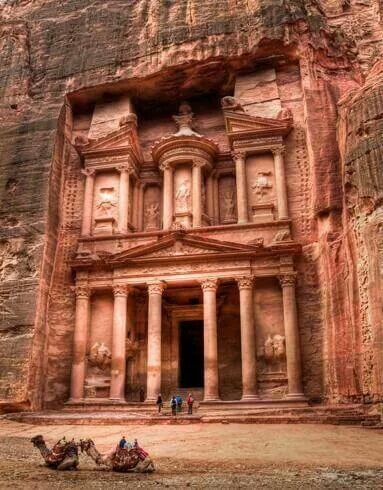

Nabateans (Arabian Desert, Petra)

Overview: An ancient Arab people who built the stone-carved city of Petra and became wealthy from controlling desert trade routes. Known for their advanced water storage systems, rock-cut architecture, and ability to thrive in arid terrain.

Inspiration for Fiction: An ancient desert civilization carved into the sides of cliffs, blending magical stonecraft with hydraulic engineering. They once ruled the desert through control of sacred wells and now guard the ruins of their golden age.

Character Idea: A young stonemason with a gift for manipulating stone is conscripted to uncover a lost chamber said to contain their ancestors’ final prophecy. But the chamber may also awaken something buried for a reason.

Pueblo Cultures (Southwestern U.S.)

Overview: Indigenous peoples such as the Hopi and Zuni built permanent settlements in arid lands, with adobe and stone architecture. Their cultures emphasize harmony with nature, communal life, and intricate ritual cycles.

Inspiration for Fiction: A people who build into cliffs and mesas, using solar mirrors to track celestial events. Their rituals maintain balance between the world of humans and the spirits of sand, wind, and flame.

Character Idea: A ritual keeper responsible for ensuring the harmony of seasons and spirits. When omens go awry and crops fail, he must travel to the sacred high desert to learn why the balance is shifting and what ancient wrong must be made right.

Aboriginal Australians (Central Deserts)

Overview: Aboriginal peoples have lived in Australia’s deserts for tens of thousands of years, navigating vast landscapes using songlines – oral maps embedded in myth and music. Their connection to the land is spiritual, ancestral, and practical.

Inspiration for Fiction: A desert culture that “sings” its way across a magical wasteland. Each songline traces the steps of the world’s creators and unlocks secret knowledge when sung at the right place and time.

Character Idea: A singer who is the last to know the full journey-song. With invaders threatening to strip-mine sacred lands, she must retrace a forgotten songline across perilous terrain to awaken the ancestral guardians bound beneath the dunes.

Tips for Ethical and Inspired World-Building

Research Deeply: If you’re drawing on real-world cultures, take the time to research their history, language, customs, and values. Avoid surface-level portrayals.

Combine Elements Thoughtfully: Rather than directly copying a single culture, consider blending aspects of multiple societies, or imagining how a culture might develop in response to new technologies or magic systems.

Create Depth: Show how the desert shapes your fictional culture’s values, myths, clothing, economy, and art. Let these elements influence your characters’ worldview and decisions.

Respect Real Histories: If you include analogues to real-world peoples, do so respectfully and avoid perpetuating stereotypes. Sensitivity readers can be helpful when dealing with specific cultural inspirations.

Deserts as Natural Defenses

Deserts can act as formidable natural barriers, protecting civilizations from invasion, conquest, or even discovery. The harshness of the terrain, the scarcity of water, and the disorienting nature of endless dunes or salt flats make deserts more effective than walls.

Strategic Isolation

Civilizations hidden deep within or behind deserts may enjoy long periods of peace and independence simply because no army can reach them without immense logistical planning. Harsh desert conditions discourage expansion, limiting the reach of empires and making these protected cultures more insular, self-reliant, or culturally distinct. Characters raised within these protected regions may view the desert as both guardian and gatekeeper, a sacred threshold no outsider should cross.

Impact on Plot and Conflict

Barrier to Conflict: Deserts can delay or prevent war. Perhaps an enemy empire lies beyond the desert, but cannot attack until it masters desert traversal, giving the protagonists time to prepare.

Cultural Superiority or Arrogance: A desert-protected civilization might develop a sense of superiority or complacency, believing they are untouchable until new technology or magic renders the desert passable.

Isolationist Tensions: What happens when outsiders finally breach the desert? Will the people welcome trade, fear invasion, or initiate preemptive strikes? Your characters might be diplomats, scouts, or warriors dealing with the consequences.

Example: The Valley of the Kings in ancient Egypt remained hidden and undisturbed for centuries thanks to its desert location. In fiction, the idea of a lost or hidden kingdom protected by the desert remains a powerful motif, seen in works like Stargate, Prince of Persia, and Black Panther’s secretive Wakanda.

Deserts as Cradles of Myth and Legend

Deserts are landscapes of extremes: blinding light and endless darkness, silence and sandstorms, death and revelation. They naturally lend themselves to mythic storytelling, both as backdrops and as characters.

Mythical Geography

Sacred Sites: Certain rock formations, dried-up rivers, or mirage-filled basins may be holy places where gods walked, prophets meditated, or ancient battles took place.

Vanishing Landmarks: Myths may speak of lost cities swallowed by the sand, temples that appear only during equinoxes, or cursed caravan routes haunted by vengeful spirits.

Celestial Portals: With vast, unobstructed skies, deserts often become places of astronomical importance. Your story might feature characters seeking prophecy through the alignment of stars, sun, or moons over sacred dunes.

Desert Spirits and Supernatural Forces

Many desert cultures have myths about spirits tied to the wind, sand, or fire, some benevolent, others wrathful. These entities might explain natural hazards or act as protectors or punishers.

In a fantasy or sci-fi setting, these “spirits” could be:

Ancient AIs with fragmented memories controlling sand drones.

Forgotten gods awakened by a solar eclipse.

Elemental beings that sleep beneath the dunes, disturbed by mining or war.

Impact on Characters

Characters raised in the desert may have internalized its mythos: seeing the dunes not as lifeless, but as sacred; the storms not as threats, but as omens. A protagonist might be on a pilgrimage to a legendary location, guided only by fragmented stories, dreams, or ancestral songlines. Skeptics may find their beliefs challenged when the desert’s legends prove real, perhaps painfully so.

Example: The Book of Exodus paints the desert as a place of divine revelation, trial, and transformation. Similarly, Dune uses the deep desert as a space where Paul Atreides becomes the messiah. The desert is not just background; it is an initiator of destiny.

Plot and Character Ideas

The Thirst of Kings

Genres: Epic Fantasy, Political Intrigue

Plot Idea: A centuries-old treaty guaranteeing access to a sacred desert spring is broken, threatening war among the five desert kingdoms.

Character Angle: A young diplomat from a minor oasis is tasked with brokering peace but uncovers evidence that the spring is drying up for a much darker reason.

Twist(s): The spring’s source is a bound elemental, and releasing it would save the desert but collapse every kingdom built on its stolen power.

Dustwalker

Genres: Science Fiction, Survival

Plot Idea: On a terraformed desert planet, travelers must hire a Dustwalker, elite guides who survive the shifting, AI-patrolled wastelands.

Character Angle: A disgraced ex-colonel hires a Dustwalker to smuggle him across forbidden zones to find his missing daughter.

Twist(s): The Dustwalker is part machine and remembers a different version of the planet – one hidden under layers of false history.

The Sand-Scribed Prophecy

Genres: Mythic Fantasy, Quest

Plot Idea: Once every thousand years, desert winds etch a prophecy onto the side of a sacred cliff. This time, it names an outsider.

Character Angle: A skeptical archaeologist discovers a new inscription and reluctantly becomes involved in a desert people’s ancient myth.

Twist(s): The prophecy is incomplete, and finishing it means choosing between saving the desert or preserving time itself.

Salt Glass

Genres: Weird Fantasy, Horror

Plot Idea: In a crystalline desert made of salt and glass, a creature that lives in reflections stalks a caravan.

Character Angle: The caravan’s glassblower must use her craft to trap the entity, but she begins seeing visions of her dead sister in the mirrors.

Twist(s): The creature feeds on grief, and the more the protagonist mourns, the more powerful it becomes.

The Mirage Pact

Genres: Science Fantasy, Espionage

Plot Idea: An empire’s desert border is protected by a “mirage zone” created by lost alien tech. Now, a breach has appeared.

Character Angle: A hybrid spy investigates, but the mirage is distorting their perception of who they are and what side they serve.

Twist(s): The breach is not a flaw; it’s an invitation from a hidden civilization who claim the empire’s founders were exiles.

The Bones Beneath

Genres: Dark Fantasy, Mystery

Plot Idea: A desert town is built atop the remains of a long-buried beast. Now, the bones are stirring.

Character Angle: A cynical grave-keeper finds ancient bones surfacing and hears whispers from them.

Twist(s): The town’s founding families swore a pact to keep the creature dormant, and now one of them is trying to resurrect it.

Sundagger

Genres: Adventure, Coming-of-Age

Plot Idea: In a land where shadows are hunted by sun spirits, a young thief steals the Sundagger, said to cut through light itself.

Character Angle: The thief only wants to sell the blade, but using it awakens a dormant ability to command light and shadow.

Twist(s): The dagger is a prison, and the ancient being inside is bargaining for freedom, promising revenge on the gods of the desert.

The Sand Choir

Genres: Post-Apocalyptic, Sci-Fi Horror

Plot Idea: A musical signal from a vast salt desert drives nearby communities into trance states. Teams sent to investigate vanish.

Character Angle: A neurodivergent sound engineer immune to the melody is drafted to track the source but hears harmonies no one else can.

Twist(s): The signal is a distress call from a buried alien being slowly awakening, and her “choir” is growing.

Oasis Zero

Genres: Cyberpunk, Eco-Fiction

Plot Idea: In a megadrought future, a self-sustaining biodome in the desert known as Oasis Zero holds the key to planetary recovery, but it’s sealed itself off.

Character Angle: A scavenger gains entry and must impersonate a long-dead geneticist to survive inside and uncover its secrets.

Twist(s): The oasis is sentient, and it’s selecting who deserves to inherit the Earth based on their relationship with the land.

Ash of the Sandwyrm

Genres: Sword & Sorcery, Monster Hunter

Plot Idea: An ancient sandwyrm has awakened, threatening to devour entire towns as it migrates toward a forgotten temple.

Character Angle: A retired warrior who once spared the creature’s egg is now hired to kill it but suspects the wyrm is being driven by a curse.

Twist(s): The temple is not a nest, it’s a tomb built to keep the wyrm’s mate sealed, and killing it would break the seal.

Veilwind

Genres: Sci-Fantasy, Romance

Plot Idea: Every 20 years, a supernatural sandstorm called the Veilwind sweeps across the desert, erasing memories but sometimes returning others.

Character Angle: A cartographer with amnesia from the last Veilwind receives letters from a lover they don’t remember.

Twist(s): The letters are from themselves, written across time, and if they don’t reach a certain ruin before the next storm, they’ll forget everything again.

The Dust Archive

Genres: Historical Sci-Fi, Lost Knowledge

Plot Idea: A shifting desert is erasing ancient ruins faster than they can be cataloged. Rumors tell of a sentient archive that relocates itself to stay hidden.

Character Angle: A disillusioned historian joins a rogue archaeological team obsessed with finding the archive and rewriting the empire’s past.

Twist(s): The archive only reveals truth to those willing to sacrifice a memory, and the more valuable the knowledge, the deeper the personal cost.

Deserts in fantasy and science fiction are anything but empty. They’re brimming with story potential – from nomadic cultures shaped by scarcity, to high-stakes trade politics, to the raw emotional power of isolation and endurance. By grounding your desert world-building in ecological logic and cultural depth, you can create a setting that is both believable and breathtaking.

So next time you look out over a sea of sand in your story, ask yourself: Who lives here? What do they fight for? What secrets lie buried beneath the dunes?

And then start digging.

Happy worldbuilding!

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

The Worldbuilder’s Toolkit: Mountain Ranges

Posted on February 13, 2026 Leave a Comment

I will do a deep dive into the topics that I covered in my world building series two years ago. This article is the first in a new series on geography and topography.

Mountain ranges have always been alluring to writers and storytellers. They are places of mystery, beauty, and danger where one can feel the weight of ancient stone and the might of nature. From Tolkien’s Misty Mountains to Frank Herbert’s Shield Wall on Dune, mountain ranges have played central roles in some of the most iconic fantasy and science fiction landscapes. Here’s a guide to help you craft interesting mountain ranges.

Where to Start

The Geography of Your Mountains

First, choose the location and decide how your mountain range formed. Mountains often arise from tectonic activity, volcanic activity, or erosion. In fantasy and science fiction, the causes can be supernatural or alien, such as a mountain range created by a long-dead giant or as remnants of an interstellar war.

A mountain’s altitude affects temperature, vegetation, and animal life. Lower slopes may be lush, while higher reaches are sparse and icy. Consider how local flora and fauna adapt to this environment—and whether magical or alien species exist here.

Add unique landmarks like jagged cliffs, hidden valleys, ancient caves, or abandoned temples. Specific terrain types (steep cliffs, alpine lakes, dense forests) can enhance the atmosphere of danger or discovery in your mountains.

Mountains as Hiding Places and Fortresses

Mountains often serve as natural refuges for those on the run. They offer countless hiding spots for outlaws, rebels, or creatures trying to avoid human encroachment. Perhaps entire communities hide in the mountains, away from prying eyes and outside authorities.

Many classic tales feature impregnable mountain fortresses. Think of how a high-altitude fortress might operate differently than one on flat land. Limited resources and steep access routes might shape daily life and add tension when provisions run low. In a sci-fi setting, this might mean that a military base high in the mountains has advanced security systems, powered by rare crystals only found in that region.

Living in the mountains requires adaptation and resilience. Characters might face extreme weather, dwindling supplies, or the loneliness of isolation. Consider how mountain-dwellers might differ culturally and psychologically from people in lower-lying regions, developing unique values and skills.

Mountains as Characters in Your Story

Treat the mountain range as a character itself, with moods and mysteries. You can give your mountains personality—through the way locals talk about them or by infusing them with natural phenomena, like eerie sounds caused by the wind in caves, or rare atmospheric lights.

Many cultures have myths tied to mountains, often involving dragons, giants, or spirits. In your world, these might be true, half-forgotten, or exaggerated legends that turn out to hold a kernel of reality. Myths about the mountain’s origin, spirits, or lost civilizations can lend your range a deeper narrative weight and mystery.

Mountains are classic symbols of challenge, enlightenment, or isolation. Think of the themes your story explores and how mountains could underscore those themes. Are your characters climbing towards enlightenment, struggling to escape isolation, or confronting the seemingly insurmountable?

Mountains as Strategic Points in Sci-Fi Settings

In a science fiction world, mountains may have entirely different compositions or origins. Imagine a mountain range on a new planet, with alien minerals and rock formations that challenge known science. Anomalous gravity fields, electromagnetic storms, or sentient mountain organisms could create unique obstacles.

Mountains in sci-fi often house military bases, research centers, or clandestine labs. The natural barrier of a mountain provides excellent protection, making it ideal for high-security installations. Your characters may need to infiltrate or defend such a location, heightening the stakes with advanced technology and challenging terrain.

A mountain range on another world could contain bizarre ecosystems with creatures or plants developed specifically for high-altitude conditions. These ecosystems might even offer critical resources for your characters, adding urgency to their journey and potentially spurring conflict with native species or rival factions.

Mountains as Natural Borders and Their Impact on Plot and Characters

Mountain ranges have historically served as natural borders, shaping not only the physical landscape but also the social, political, and economic divides within a region. By placing a mountain range along the boundary between nations, factions, or even species, you can add complexity to your world’s politics and your story’s conflicts. Here’s how mountain-bordered territories can influence your plot and characters.

Physical Division of Regions and Nations

Mountains often separate groups, leading to cultural differences and misunderstandings. For example, two societies on either side of a mountain range might develop different languages, customs, and ideologies over generations. This divide can foster prejudice or mistrust, or even inspire intrigue for characters who wish to bridge the gap.

A mountain border often means uneven resources on either side. One nation may have fertile valleys, while the other has access to mineral-rich mountains. This imbalance can create economic dependence, tension, or even conflict. Characters caught in the middle of these tensions might need to find creative ways to negotiate or exploit the situation.

Mountains are formidable obstacles for invading forces, so they’re often natural borders for defensively minded kingdoms. A character might come from a heavily fortified mountain kingdom, secure in its isolation, or from a neighboring region eager to breach the mountain defenses for trade or conquest. These strategic concerns can lead to alliances, betrayals, or secret passageways and hidden tunnels.

Political and Strategic Implications

When mountains mark a boundary, nations on either side may squabble over territory in the foothills or contest ownership of rare resources found within the mountains. Your plot might involve border skirmishes, political negotiations, or espionage as one side attempts to gain an advantage over the other.

Mountain borders remain unclear in many places. Foggy highlands, unmapped passes, and treacherous peaks could create gray areas between nations. Characters might find themselves in disputed regions, encountering conflicting claims and risking punishment if caught by the “wrong” side. Such a scenario can add moral complexity, especially if innocent people or villages live in these contested zones.

Some mountain ranges serve as neutral territories or buffer zones between rival factions. This could allow for secretive meetings, shady trade deals, or third-party agents who use the neutrality to their advantage. Characters might come to the mountains to broker deals, gather intelligence, or navigate alliances.

Impact on Characters and Their Journeys

For characters needing to cross the border, a mountain range adds a literal and symbolic obstacle. Such a journey requires physical endurance and mental resilience, which can bring out hidden qualities in your characters. This can serve as a rite of passage or a way for them to prove their loyalty or bravery.

Mountains as borders create natural havens for outcasts, refugees, and rebels who wish to avoid authorities on either side. Characters who seek refuge or escape might join a hidden mountain community or forging an alliance with other wanderers. These interactions can lead to the blending of cultures, unexpected alliances, or new sources of conflict.

In a story with mountain-bordered regions, you may have characters who serve as messengers, diplomats, or spies. Characters tasked with bridging the divide must understand both sides, navigate diverse customs, and deal with the physical hardships of mountain travel. Their efforts to negotiate or mediate can add depth to political subplots, as well as emotional stakes, if they feel connected to both lands.

Symbolic and Emotional Significance of Borders

Mountains that serve as borders can create emotional tension for characters with family or friends on the other side. The border’s harsh realities may prevent regular visits or communication, amplifying a sense of loss, nostalgia, or duty. These characters might risk their lives crossing the mountain to reunite with loved ones, defying political or social boundaries.

Characters from opposite sides of a mountain border might defy social expectations by forming bonds. Such relationships could be strained by the cultural, legal, or political hurdles imposed by the border. Characters from different lands may meet in secret or face danger for their connection, adding a layer of personal struggle to the larger geopolitical tension.

Mountains as Natural Protectors of Civilizations

Mountain ranges can act as powerful natural fortifications, shielding civilizations from external threats and shaping the unique ways in which these societies develop. Historically, civilizations nestled within or behind mountain ranges often experienced fewer invasions and developed distinct cultural identities because of their isolation. In your fantasy or science fiction story, mountains as protective barriers can affect plot dynamics, character motivations, and the development of unique societies. Here’s how protected mountain civilizations can enrich your world.

Defense Against Invaders and External Threats

A civilization protected by mountains has a defensive advantage, as invading forces must navigate treacherous passes, steep cliffs, and extreme weather. Characters from such a society may feel a sense of security and even superiority because of their fortress-like home. This defense could inspire pride or insularity among its people, who may view outsiders with suspicion or contempt.

If an invading force seeks to conquer a mountain-protected civilization, their attempts can create high-stakes plot points. Characters defending their homeland might rely on guerrilla tactics, taking advantage of the terrain to ambush enemies. This setting allows for intense and creative battle scenes where knowledge of the mountains proves as valuable as skill in combat.

The mountains may protect against human invaders, but they could also conceal supernatural or alien dangers. Ancient beings, magical forces, or hostile alien species may lurk within the mountains, threatening to spill out into the protected civilization. Characters may have to confront these hidden threats, especially if they discover how the mountains keep these forces in check.

Isolation and Cultural Distinctiveness

Isolation fosters a distinctive cultural identity, with customs, language, and beliefs that set mountain-protected civilizations apart. Characters from these societies might have unique ways of life influenced by the terrain, such as high-altitude agriculture, specialized crafts, or spiritual practices centered on mountain deities. These differences could lead to misunderstandings, curiosity, or fascination among outsiders, adding depth to cross-cultural interactions.

For societies shielded by mountains, the outside world may be a source of myth or mystery. This lack of knowledge can affect characters who venture beyond their homeland, who might feel awe, fear, or excitement upon encountering new lands and people. Their perceptions of the outside world, based on stories or legends, could create interesting plot twists as they confront reality.

The protection of mountains can breed a rigid mindset, resistant to change or outside influence. Characters within these societies might struggle between upholding tradition and embracing progress, especially if new ideas, technologies, or magical practices seep in from beyond the mountains. This tension could manifest in family dynamics, political intrigue, or clashes between elders and younger generations.

Trade and Resource Limitations

Protected mountain civilizations often develop resourceful ways to sustain themselves, relying on unique local resources. Characters might be skilled in crafting or farming techniques suited to high-altitude life. However, limited resources can also drive plot points—such as a search for rare materials, bartering, or even resource-based conflicts if outside forces covet the mountain’s hidden riches.

Mountains can restrict access, making trade routes valuable and tightly controlled. Protected societies may have one or two key passes that facilitate trade with outsiders, creating opportunities for toll collection, smuggling, or disputes over who controls access. Characters might become involved in maintaining or defending these routes, facing danger from both the elements and rival groups vying for control.

Some protected civilizations may wish to expand beyond their mountain refuge or explore the world outside. This desire could lead characters to form alliances, make perilous journeys through mountain passes, or face opposition from those who fear losing their insular way of life. Such a conflict between isolationists and explorers can create rich interpersonal drama and character growth.

Impact on Characters and Their Worldview

Characters from a protected civilization may have limited understanding of the world beyond, leading to an insular mindset. This can affect their interactions with outsiders, who may see them as naïve or closed-minded. These characters might struggle with prejudice or fear of the unfamiliar, while others may feel a deep curiosity and yearning to explore.

The knowledge of living in a protected environment can foster a strong sense of duty in characters, especially if they realize that their safety is a luxury not shared by others. Some characters might feel called to defend their people’s haven, while others could be driven to protect or aid those without similar protection. This sense of responsibility can motivate characters to face the unknown and risk their own security for a larger cause.

A protected civilization’s resistance to change can be a powerful source of internal conflict. Characters within such a society may clash over whether to maintain their traditional ways or open to new ideas, allies, or technologies. Those advocating for progress might face suspicion or backlash, while defenders of tradition grapple with the realization that isolation may not be sustainable.

Mountains as Settings for Myth and Legend

Mountains have long held a place in the mythologies of cultures worldwide, representing both the heights of divinity and the depths of mystery. In fantasy and science fiction, mountains can serve as symbolic locations where legends come alive, becoming places where the natural and supernatural intersect. Using mountains as settings for myth and legend allows you to infuse your world with a sense of ancient wonder and danger, giving characters an epic backdrop for quests, mysteries, and supernatural encounters.

Mountain Deities and Divine Realms

Many cultures believe that gods and spirits dwell in mountains, and your world’s mountains can be no different. These peaks may house powerful deities, spirits, or beings that shape the weather, control the seasons, or guard hidden realms. Characters might make pilgrimages to these sacred peaks to seek blessings, consult an oracle, or bargain with an ancient entity. This divine connection adds gravitas to mountains, imbuing them with a sense of reverence and danger.

A sacred mountain often represents the concept of the axis mundi, or the world’s center. In your story, a mountain might serve as a cosmic bridge between realms or dimensions, allowing communication between mortals and gods or even travel to other worlds. Characters venturing to the top might gain wisdom, insight, or magical powers, while facing tests along the way that reinforce the mountain’s role as a spiritual journey.

Not all mountain deities are benevolent. Local populations may shun certain peaks, believing them cursed or haunted because of legends of vengeful spirits or dangerous curses. Characters approaching these forbidden mountains could face supernatural dangers, discover remnants of past civilizations, or encounter forces that compel them to confront their deepest fears.

Legends of Lost Cities and Hidden Treasure

Mountains often hide secrets of ancient civilizations—ruined temples, long-lost cities, or relics of forgotten eras. Perhaps the remains of a powerful kingdom lie buried high in the peaks, waiting for those daring enough to rediscover them. Characters might go on quests to find these mythical places, motivated by the promise of knowledge, power, or forbidden magic.

Legends of hidden treasures are a staple in mountain lore. These treasures could be powerful artifacts, gemstones with magical properties, or lost technology left by a previous civilization. Characters might undertake treacherous journeys to locate these treasures, facing both natural hazards and mythical guardians along the way. The mountain’s legends could hint at trials or sacrifices required to get these prizes, adding moral stakes to the quest.

Legendary guardians often protect lost cities and treasures. Your mountain myths could feature dragons, spirits, giants, or other creatures who guard these ancient sites. Characters might have to confront or appease these guardians, creating thrilling encounters that deepen the sense of the mountain as a place of legend and mysticism.

Mountains as Places of Transformation and Trial

Many myths depict mountains as sites where heroes prove themselves. To make your story more engaging, you could have characters go through a rite of passage in the mountains, forcing them to survive harsh conditions, complete a sacred ritual, or defeat a mythical beast. This journey can serve as a transformative experience, forcing characters to confront their limitations, fears, and inner conflicts.

Mountains in myth are often testing grounds for those deemed worthy of divine favor or great responsibility. A prophecy may draw characters to the mountains, hoping to fulfill a destiny, gain supernatural abilities, or uncover the truth about their heritage. The trials they face—harsh environments, mythical creatures, or inner demons—become metaphors for personal growth and resilience.

Many mountain myths depict peaks as places of spiritual purification. Characters might travel to a sacred mountain seeking redemption, knowledge, or healing. Along the way, they could undergo a transformation, physically or spiritually, as they shed old identities or burdens. This journey of renewal adds an emotional layer to the mountain’s significance, allowing it to become a place where characters heal and develop.

Portals and Pathways to Other Realms

Legends of secret portals are common in mountain lore, with peaks or caves serving as entrances to hidden realms. Your world’s mountains might contain magical or technological gateways to other dimensions, celestial realms, or underground civilizations. Characters could stumble upon these portals by accident or seek them deliberately, leading to encounters with beings or worlds vastly different from their own.

In myth, mountains are often associated with the afterlife or spiritual planes. Characters could journey up a sacred peak in search of a loved one’s soul, divine judgment, or forbidden knowledge. This journey might involve supernatural trials, encounters with spirits, or the unveiling of truths about life and death, adding existential weight to the mountain’s mystique.

In some stories, mountains themselves are conscious beings, ancient and wise. Characters might encounter a mountain spirit or face trials set by the mountain itself, as if it senses their purpose or intentions. These sentient mountains could communicate through signs, visions, or even direct speech, guiding or challenging characters as they ascend.

Folklore and Superstitions

Every mountain might have its own lore, passed down through generations. Local inhabitants could warn travelers of specific dangers, such as cursed cliffs, ghostly apparitions, or hidden lakes with transformative powers. These superstitions could foreshadow events in your story or reveal hidden truths that characters gradually uncover.

Mountains often serve as observatories for celestial events, from solstices to eclipses. In your world, a mountain might be central to a festival or ritual held at a specific time, when certain stars align, or phenomena occur. Characters taking part in these traditions might witness extraordinary events or receive divine messages, reinforcing the mountain’s mythical status.

Mountain legends can serve as cautionary tales, warning characters of dangers that go beyond the physical. Perhaps there are stories of travelers who were greedy or reckless and met untimely ends, or tales of cursed artifacts and haunted peaks. Characters who disregard these warnings might face tragic consequences, while those who heed them could uncover hidden wisdom or insights.

Impact on Plot and Characters

Legendary mountains can motivate characters to embark on epic journeys, whether to fulfill a prophecy, reclaim a lost relic, or achieve enlightenment. A personal desire to uncover family roots, understand ancient mysteries, or seek retribution may fuel their journey. These stakes add emotional weight to the mountain’s allure.

Cultural beliefs tied to your mountain myths can influence your characters’ worldview, leading to conflict or cohesion. Some characters might uphold the myths and traditions, while others might challenge them, leading to tension within a group or society. This cultural clash can drive plot points, especially if myths play a role in guiding key decisions or setting societal expectations.

Characters who unravel mountain legends might gain knowledge or power that becomes pivotal to the story. They may discover secrets about their world’s creation, tap into ancient magic, or learn about forces that still influence the present. This newfound knowledge can shift power dynamics, creating intrigue and conflict as characters decide how to use or protect what they’ve learned.

Plot and Character Ideas for Mountain-Centric Stories

Mountains offer unique story opportunities, where the landscape itself shapes characters’ journeys, motivations, and the conflicts they face. I’ve compiled some plot and character ideas for stories that focus on mountains or are strongly influenced by them, each with an example from popular media to illustrate the concept.

The Quest for a Sacred Peak

The protagonist must ascend a sacred mountain to retrieve a powerful artifact or receive wisdom from a mystical figure. Along the way, they face both physical challenges and internal doubts, forcing them to grow before reaching the summit.

The main character, perhaps a reluctant hero or untested youth, starts off doubting their abilities but learns to trust their instincts and inner strength as they face each obstacle the mountain presents. Their journey is both physical and spiritual, symbolizing their ascent to self-realization.

In The Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien, Frodo and Sam must journey to the dangerous and almost insurmountable Mount Doom to destroy the One Ring. The mountain serves as both a literal and symbolic test of their resilience and purity of heart.

The Refuge of Rebels or Outcasts

A mountain range serves as a refuge for rebels, exiles, or a hidden society. The protagonist, perhaps a fugitive or a freedom fighter, joins this isolated community, which becomes the last stronghold against an oppressive force.

A character might initially be focused on revenge or survival, but the mountain society teaches them the importance of unity, sacrifice, and strategic thinking. They might eventually become a leader who organizes the resistance and uses the mountain’s natural defenses to fend off enemies.

In The Hunger Games: Mockingjay by Suzanne Collins, District 13, a hidden district with strongholds in the mountains, becomes the heart of the rebellion against the Capitol. The mountain-dwelling community’s values and resourcefulness influence characters like Katniss, transforming her into the symbolic Mockingjay.

The Curse of the Haunted Peak

Legends tell of a mountain cursed by spirits or ancient powers. Characters journey there to uncover its secrets, retrieve a treasure, or break the curse, but they encounter strange, supernatural phenomena that challenge their perceptions of reality.

The protagonist, possibly a skeptic or treasure hunter, may initially dismiss the legends but becomes increasingly haunted by them. Over time, they come to respect and fear the mountain’s powers, experiencing a transformation from arrogance to humility, and perhaps sacrificing to break the curse.

In Pet Cemetery by Stephen King, while not a mountain, the cursed burial ground serves a similar purpose as a place with dark legends that people visit, despite the warnings, in search of something they desperately desire. Its influence transforms those who interact with it, often to disastrous effect.

The Hidden Kingdom

High in the mountains, an ancient, isolated kingdom or city thrives, hidden from the rest of the world. The protagonist stumbles upon it, discovering an entirely different society that either needs protection from a threat or is planning an expansion that could destabilize the surrounding regions.

A curious explorer or outsider might find themselves torn between loyalty to their homeland and a growing attachment to the mountain kingdom. They could face tough choices about allegiance and whether to reveal the hidden kingdom’s existence to the outside world.

In Black Panther (2018), the isolated kingdom of Wakanda hides behind mountains and advanced technology, protecting itself from outsiders. T’Challa, as both ruler and protector, struggles with whether to maintain secrecy or share Wakanda’s resources with the world, leading to profound character development.

The Mountain as the Ultimate Test

The protagonist’s culture has a rite of passage involving a perilous mountain journey. The culture sends them to scale the mountain, survive its dangers, and find a rare object within its depths, to prove their worthiness. This challenge serves as a transformative experience.

The protagonist might be a young individual, eager to prove themselves or find their purpose. Facing dangerous elements, isolation, and physical exhaustion, they emerge changed—more mature, resilient, or having confronted a significant internal fear.

In The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien, Bilbo’s journey to the Lonely Mountain to confront Smaug the dragon is an ultimate test of courage and wits. Though he starts as an unlikely hero, the challenges he faces in the mountain redefine him and change his life permanently.

The Environmental Mystery or Catastrophe

A series of strange events—rockslides, mysterious lights, or unusual animal behavior—occurs on or near the mountains, prompting the protagonist to investigate. They uncover a hidden threat, perhaps environmental degradation, supernatural forces, or an alien presence.

A scientist, investigator, or local villager becomes increasingly obsessed with solving the mystery. Their discoveries may come at a personal cost, as they risk their safety or even face disbelief from their community. They ultimately have to decide between preserving the mountain’s mysteries or exposing the truth to save others.

In The X-Files, particularly episodes like “Ice” and “Firewalker,” Agents Mulder and Scully often investigate mysterious phenomena in isolated, mountainous areas, uncovering secrets about human nature, supernatural forces, or alien life. The mountain environments add an air of danger and isolation, amplifying the mystery.

The Rivalry for the Mountain’s Riches

Two factions or kingdoms both desire the wealth or resources hidden within a mountain range—precious metals, gemstones, or a powerful magical element. Characters from either side face off, with the mountain itself becoming a battleground.

Characters might start with strong loyalties to their side, but the brutality of the conflict, along with their time in the mountains, challenges their beliefs. They might question the cost of war, forming unlikely alliances, or betraying their faction to end the bloodshed.

In Avatar (2009), the Na’vi, a native tribe on the planet Pandora, live in and around the Hallelujah Mountains, which contain valuable minerals sought by humans. Jake Sully, initially loyal to the human faction, switches allegiances as he learns more about the Na’vi and the significance of the mountains, ultimately leading him to fight for their protection.

The Lost Soul or the Mountain Oracle

Legends say that a wise oracle or an ancient sage lives atop a distant mountain, providing guidance to those brave enough to make the climb. The protagonist seeks this figure, looking for wisdom, healing, or answers to a profound question.

This journey challenges the character to face their inner demons, regrets, or unresolved trauma. By the time they reach the oracle, they are ready to hear the truth or gain the insight they seek, whether it’s healing, purpose, or a last goodbye to a loved one.

In Kung Fu Panda 2 (2011). Po journeys into the mountains to find inner peace and clarity about his past. His journey to the peaks is both a physical and emotional journey, symbolizing his self-acceptance and inner strength. The mountain setting heightens the mystical quality of his journey.

Real-Life Mountain Cultures as Inspiration for Fictional Worlds

Mountain cultures throughout history have developed unique ways of life, shaped by isolation, challenging climates, and rugged landscapes. These societies often share traits of resilience, resourcefulness, and deep cultural roots tied to their surroundings. Drawing from real-life mountain cultures can help you create rich, authentic characters and societies for your fantasy or science fiction settings. Here are some examples of historical mountain cultures and ideas on how they can inspire fictional characters or civilizations.

The Inca Empire (Andes Mountains)

The Inca Empire, centered in the Andes Mountains, was famous for its advanced agricultural techniques, including terracing and irrigation to farm on steep slopes. They developed a network of mountain roads and bridges that connected their vast empire, as well as complex religious practices and cosmology that revered natural features like mountains, rivers, and the sun.