The Writer’s Guide to Realistic Healing Timelines and Scarring

Posted on January 30, 2026 Leave a Comment

In fiction, injuries often happen at the speed of plot. A hero is impaled one day and sword-fighting the next. A broken arm is forgotten by chapter three. But realistic recovery doesn’t just make your story believable, it deepens emotion, develops character, and adds tension through limitation.

Healing takes time. It also leaves traces, not only in the body, but in the psyche. Knowing how long it takes a wound to close, a bone to mend, or a scar to fade gives your story the grounding it needs to resonate.

The Variables That Affect Healing

Before we get into injury types, remember that no two recoveries are identical.

Healing depends on:

Severity and location of injury: A leg wound takes longer to heal than an arm wound because it bears weight.

Age and health: Young, well-nourished characters recover faster; the elderly, malnourished, or sick recover slower.

Medical care: A clean wound in a hospital heals faster than one packed with herbs in a medieval tent.

World-building factors: Fantasy or sci-fi settings might include magic, advanced biotech, or alien physiologies that alter these timelines but internal logic should stay consistent.

Bone Injuries (Fractures, Dislocations, Amputations)

Minor Fractures (fingers, toes)

Healing Time: 3–6 weeks

Residual Effects: Stiffness, weakness, occasional pain in cold weather.

Scarring: Minimal external scarring unless surgical repair.

Major Fractures (limbs, ribs)

Healing Time: 8–12 weeks, sometimes months if complicated.

Residual Effects: Muscle atrophy, pain, visible deformity if poorly set.

Scarring: Surgical scars or callus formation along the bone.

Dislocations

Healing Time: 2–6 weeks, depending on the joint.

Residual Effects: Recurring instability, loss of full range of motion.

Scarring: None externally, but connective tissue often weakens permanently.

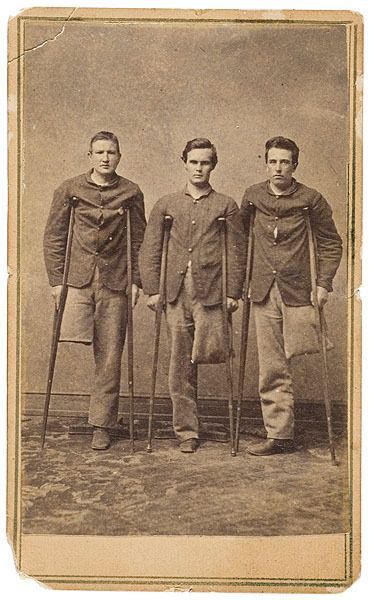

Amputations

Healing Time: 6–12 weeks for wound closure; years for full adaptation to prosthetics.

Residual Effects: Phantom limb pain, muscle contracture, altered balance.

Scarring: Pronounced; hypertrophic or keloid scarring common near sutures.

Head and Brain Injuries (Concussions, Blunt Trauma)

Concussions and Mild Traumatic Brain Injuries

Healing Time: Days to months. Some symptoms (headache, fogginess) linger for weeks.

Residual Effects: Memory gaps, dizziness, mood swings, chronic headaches.

Scarring: None visible, but sometimes symbolic (a faint scalp scar, a recurring tremor).

Severe Head Trauma

Healing Time: Months to years; recovery may never be complete.

Residual Effects: Cognitive deficits, paralysis, speech or vision loss.

Scarring: Surgical scars (stapled incisions, shaved patches), sunken areas from bone removal.

Soft Tissue Injuries (Sprains, Strains, Ligament Tears, Bruises)

Minor Sprain or Strain

Healing Time: 1–3 weeks.

Residual Effects: Mild stiffness or weakness.

Scarring: None visible.

Severe Sprain / Torn Ligament or Tendon

Healing Time: 6 weeks to 6 months; surgical repair extends recovery.

Residual Effects: Chronic instability, reduced mobility, arthritis risk.

Scarring: Small surgical scars or thickened tissue around the joint.

Bruises and Contusions

Healing Time: 1–3 weeks depending on depth.

Scarring: None, though deep trauma may cause long-term pigmentation changes.

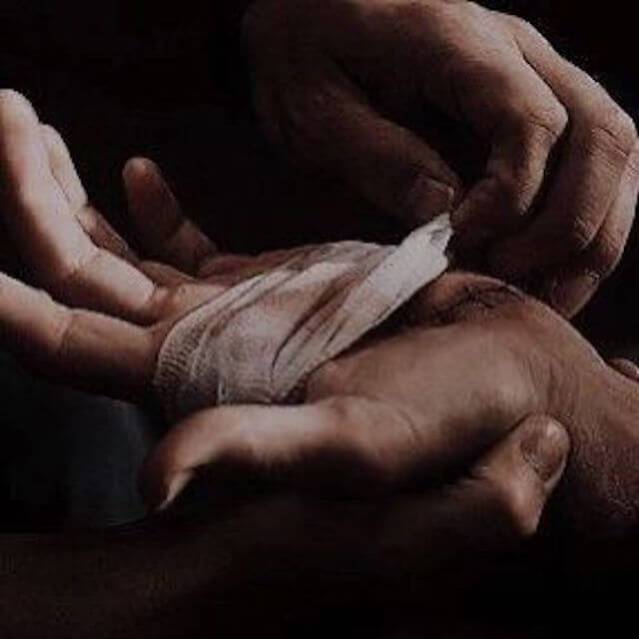

Penetrating Injuries (Cuts, Punctures, Stabs, Gunshots, Bites)

Superficial Cuts and Lacerations

Healing Time: 3–10 days.

Scarring: Minor or none unless infected.

Deep Lacerations / Stab Wounds

Healing Time: 4–8 weeks.

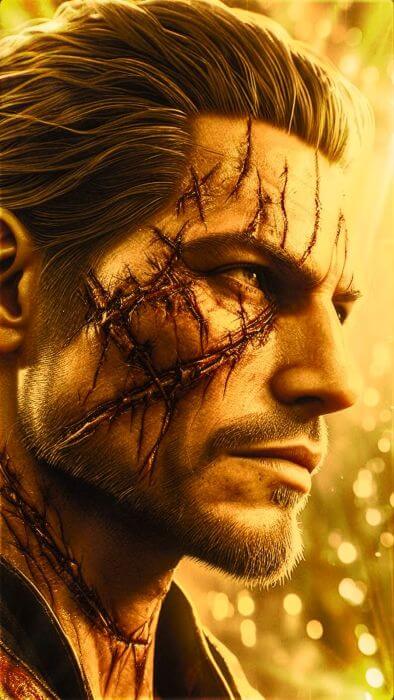

Scarring: Linear, may thicken or discolor depending on depth and care.

Gunshot Wounds

Healing Time: 2–6 months depending on trajectory and infection.

Residual Effects: Chronic pain, nerve damage, muscle weakness.

Scarring: Entry and (if present) exit wounds; tissue puckering or burn marks.

Punctures (Arrows, Animal Fangs)

Healing Time: 3–8 weeks, longer if infection develops.

Scarring: Round, pitted, or dimpled; faint unless repeatedly reopened.

Bites / Claw Wounds

Healing Time: 2–6 weeks if cleaned; risk of infection can double recovery time.

Scarring: Jagged or uneven due to tearing rather than slicing.

Thermal Injuries (Burns, Frostbite, Heatstroke)

First-Degree Burns

Healing Time: 3–7 days.

Scarring: None.

Second-Degree Burns

Healing Time: 2–3 weeks.

Scarring: Pigmentation changes; shiny or blotchy patches.

Third-Degree Burns

Healing Time: Months; may require grafts.

Scarring: Severe, often disfiguring. Limited flexibility in affected skin.

Frostbite

Healing Time: Weeks to months; amputations possible.

Scarring: Blotchy, waxy skin; permanent tissue loss or deformity.

Heatstroke / Dehydration

Healing Time: Days for mild cases; weeks if organ damage.

Scarring: None external, but may cause long-term heart or kidney issues.

Internal and Organ Injuries (Internal Bleeding, Infection, Poisoning, Venom)

Internal Bleeding / Organ Damage

Healing Time: 4–12 weeks depending on severity.

Residual Effects: Chronic pain, anemia, or fatigue.

Scarring: Internal adhesions; surgical scars externally.

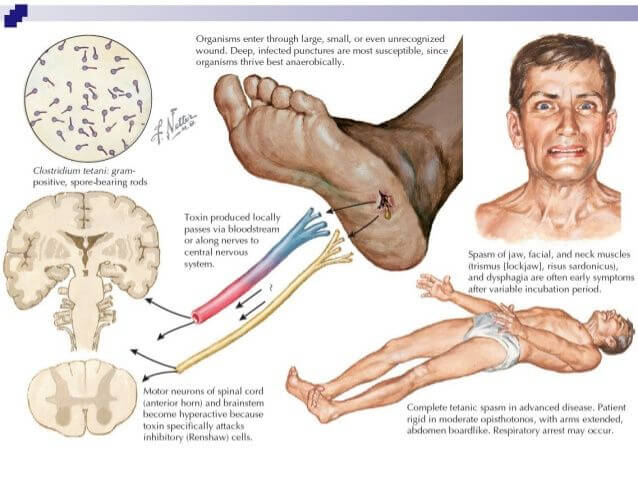

Infections

Healing Time: Variable, mild infection (days), serious sepsis (months or lifelong effects).

Residual Effects: Organ damage, chronic fatigue, scarring around infected tissue.

Poisoning / Venom

Healing Time: Hours to months depending on toxin.

Residual Effects: Nerve damage, weakness, chronic pain.

Scarring: Possible necrosis or injection-site discoloration.

Eye Injuries

Corneal Scratch / Mild Trauma

Healing Time: 2–7 days.

Residual Effects: Light sensitivity for weeks.

Scarring: None visible unless severe.

Puncture or Rupture

Healing Time: 4–12 weeks for surgical stabilization.

Residual Effects: Partial or complete vision loss.

Scarring: Milky corneal opacity, visible deformity, or prosthetic eye.

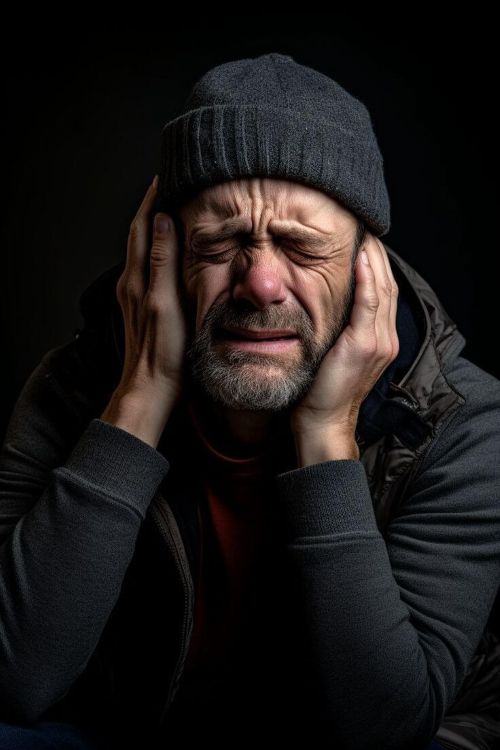

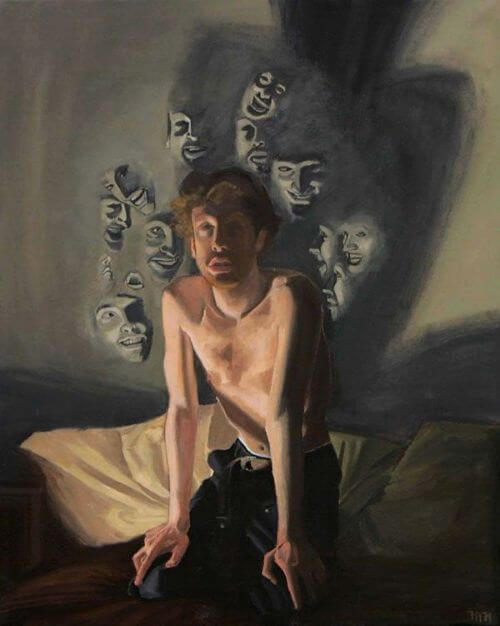

Psychological and Long-Term Effects

Post-Traumatic Stress / Anxiety / Depression

Healing Time: Months to years; sometimes lifelong management.

Residual Effects: Nightmares, avoidance behaviors, emotional numbness.

Scarring: Invisible but narrative, affects dialogue, body language, and trust.

Chronic Pain and Fatigue

Healing Time: None, managed, not cured.

Residual Effects: Mood changes, reduced energy, altered gait or posture.

Scarring: May change muscle shape or create uneven wear in joints.

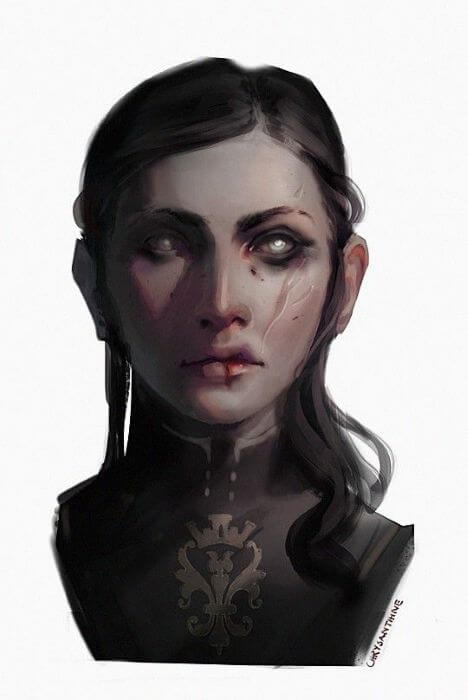

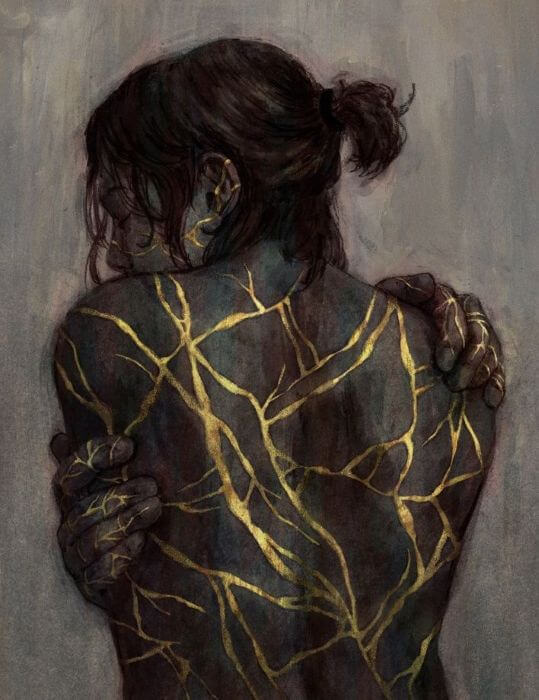

Writing Realistic Scars

Scars are more than marks. They’re memory in tissue. They can define a character’s past, status, or choices.

Types of Scars

Flat / Faint: Small cuts or clean surgical incisions.

Raised / Hypertrophic: Common in burns or repeated wounds.

Keloid: Thick, rope-like overgrowth of scar tissue (varies by genetics).

Contracture: Tightened, shiny scars from severe burns.

Discoloration: From pigment loss or excess after deep injuries.

Healing Timeline for Scars

2–3 weeks: wound closes.

1–3 months: scar tissue forms, may appear red or raised.

6–12 months: scar fades, flattens, or darkens.

1+ year: scar stabilizes; some never fade completely.

Tips for Writers

Describe how scars feel, not just how they look: itchy, tight, aching in cold.

Emotional context matters: pride, shame, trauma, or identity.

Scars can change how a character moves, dresses, or sees themselves.

Healing Timelines and Scarring Across Genres

Realistic recovery isn’t just a matter of anatomy, it’s a reflection of era, culture, and worldview. Whether you’re writing a medieval peasant, a modern trauma survivor, a starship medic, or a fantasy healer, your genre dictates what healing looks like, how long it takes, and what scars mean within that world.

Contemporary Fiction

Modern medicine has drastically shortened recovery times and reduced mortality. Broken bones can be set within minutes. Infections that once killed are handled with antibiotics. Skin grafts, physiotherapy, and reconstructive surgery can minimize scarring.

How to Depict It

Focus on rehabilitation, therapy, and mental recovery as much as the physical. The emotional consequences, pain management, PTSD, survivor’s guilt, often carry more weight than the wound itself.

Injuries heal relatively fast, but social recovery can lag: returning to work, rebuilding relationships, or confronting visible scars in a society obsessed with perfection.

Scars often symbolize resilience, trauma, or transformation rather than social stigma.

Example: A car accident victim may walk again in six months, but it takes years before she can drive without panic.

Narrative Tip

Use the precision of modern medicine to highlight what cannot be fixed. A perfect surgical scar doesn’t mean perfect healing.

Historical Fiction

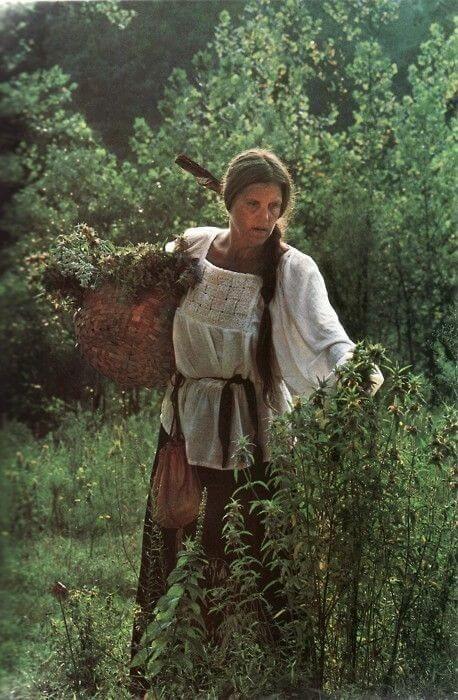

Before the 19th century, injuries were slow to heal and often fatal. Infection, blood loss, and shock were constant threats. Humoral theory, herbalism, and superstition limited medical understanding. Scarring was not cosmetic, it was survival.

How to Depict It

Reflect the slowness and uncertainty of healing. A fever could last weeks. A simple cut could turn septic. A fracture might never set properly.

Herbal remedies, poultices, and prayers were common. Even successful treatments might leave lifelong pain or disability.

Scars often carried social meaning: a warrior’s badge of honor, a servant’s disfigurement, or a witch’s supposed “mark.”

Example: A 14th-century soldier survives a sword wound to the thigh but walks with a limp for life. The wound closes in weeks, but the infection takes months to resolve if it doesn’t kill him first.

Narrative Tip

Let imperfection define authenticity. A smooth recovery feels false; a slow, uneven one builds tension and realism.

Fantasy

Fantasy allows healing to be sped up or distorted through magic, divine power, alchemy, or mythical herbs. Yet too much instant recovery can rob a story of consequence.

How to Depict It

Set clear rules for magical healing. What does it cost? Time? Energy? Life force? Magical ability?

Healing might repair the body but not the soul. A character can be made whole yet still haunted.

Scars can hold mystical significance: runic marks, remnants of curses, or proof of divine intervention.

Consider world-building consistency: if magic can heal everything, why do hospitals or healers exist?

Example: A mage heals a fatal arrow wound by transferring the pain to herself, leaving her scarred while her patient remains unmarked. Magic fixes flesh, not guilt.

Narrative Tip

Let magical healing create moral tension. Fast recovery is powerful, but it should always come with cost or consequence.

Science Fiction

In futuristic or alien settings, technology pushes recovery beyond human limits: nanobots mend cells, cloning replaces limbs, cybernetics restore lost senses. But the question isn’t can they heal; it’s what does that mean for the person who’s healed?

How to Depict It

Decide how advanced your world’s medicine truly is. Does everyone have access, or only the privileged?

Healing may be instant but dehumanizing. A new limb feels alien, or memory editing erases pain but also identity.

Scars might be cosmetic choices in a world that can erase them: symbols of rebellion, authenticity, or memory.

A technologically repaired body can still have emotional or moral wounds that machines cannot touch.

Example: A starship captain with a cybernetic arm feels phantom pain every time he enters hyperspace. His body healed, but his mind was still bound to loss.

Narrative Tip

In speculative settings, scars become metaphors for what it means to be human. They remind us that perfection has a price.

Healing and Scarring Across Genres

Realistic healing timelines and the lasting marks of injury – both physical and emotional – should always reflect the world your characters inhabit. In fiction, how fast a character heals, what kind of scar remains, and how society responds to it can reveal far more about setting and tone than any description of armor or architecture. Each genre approaches injury and recovery through its own lens of culture, science, and belief.

Contemporary Fiction

Medical Context

Modern medicine makes recovery faster and more complete than at any other time in history. Doctors set broken bones with precision, treat infections with antibiotics, and repair or mitigate even severe burns or amputations through surgery and therapy. Yet, while physical recovery is often swift, emotional and psychological recovery can stretch on for years.

Depicting Healing

Timelines: A character might leave the hospital within days but require months of rehabilitation or physical therapy.

Scarring: Minimal for most injuries; reconstructive surgery and skincare can make scars nearly invisible, though some remain as faint reminders.

Focus: Emotional scars, trauma, and societal pressure to “move on.”

Symbolism: Scars can represent survival, transformation, or stigma depending on how society or the character views them.

Example: A car accident survivor physically recovers within months but avoids mirrors for years, unable to confront the faint surgical scars along her face.

Writer’s Tip

Modern medicine removes many external stakes, so the emotional and relational consequences of injury become the story’s heart. Show how a character copes, not just how they heal.

Historical Fiction

Medical Context

Before antiseptics, anesthesia, or antibiotics, injury meant pain, uncertainty, and long recovery times if survival was even possible. A seemingly minor wound could turn fatal. Infection, malnutrition, and lack of rest made healing unpredictable.

Depicting Healing

Timelines: Even minor injuries take weeks; serious wounds may last months or leave permanent impairment.

Scarring: Common and severe. Surgery was crude, wounds often reopened, and scar tissue formed unevenly.

Focus: The realism of suffering, endurance, and resourcefulness in a pre-scientific world.

Symbolism: Scars serve as visible testaments of survival, honor, or divine will. They can also carry social consequences, marking a servant, criminal, or warrior.

Example: A 13th-century soldier recovers from a sword wound over a painful summer. The scar hardens into a pale ridge across his thigh, and his limp becomes a permanent reminder of the price of loyalty.

Writer’s Tip

In historical fiction, recovery shapes character and fate. Let slow healing influence the plot and pacing. It grounds the reader in the era’s harsh reality and makes endurance meaningful.

Fantasy

Medical Context

Fantasy allows for miraculous healing, but realism still matters. Magic, divine power, or enchanted herbs might speed recovery, yet too much convenience undermines tension and emotional depth.

Depicting Healing

Timelines: You can compress healing but establish clear rules and costs. Magical recovery might drain energy, shorten lifespan, or require rare materials.

Scarring: Magical healing may prevent scars or leave symbolic ones. A holy blessing might erase the wound but mark the skin with light or sigil patterns.

Focus: The balance between power and price.

Symbolism: Scars often carry magical or spiritual significance: proof of a curse, divine favor, or transformation.

Example: A priestess who channels her own vitality heals a wounded knight. The wound vanishes overnight, but her hands bear ghostly burn marks where she touched his skin.

Writer’s Tip

Avoid making healing too easy. Restrict the frequency of magic use or make it personally taxing. This keeps tension alive and gives injuries narrative weight.

Science Fiction

Medical Context

Futuristic medicine opens the door to regrowth, regeneration, and cybernetic repair, but perfection comes with philosophical questions. What does it mean to heal when technology can rebuild you completely?

Depicting Healing

Timelines: Healing can be nearly instantaneous through nanotech, cloning, or tissue regeneration. But adaptation to those changes should take time.

Scars can be obsolete or chosen. In a world of synthetic perfection, a scar can symbolize authenticity or rebellion.

Focus: The divide between physical restoration and emotional alienation.

Symbolism: Healing technologies blur identity. Where does humanity end and machinery begin?

Example: A soldier wakes with an artificial arm after a catastrophic injury. The prosthetic is flawless but he can still feel phantom pain from the limb he no longer has.

Writer’s Tip

Advanced healing should raise new dilemmas rather than remove them. If your world can heal the body instantly, ask what it does to memory, morality, or soul.

Plot and Character Ideas

The Long Winter of Bones

Genre: Historical Fiction / War Drama

Plot Idea: After a brutal battle, a medieval knight survives a shattered leg that takes months to heal. While trapped in a remote monastery for the winter, he questions the ideals that sent him to war.

Character Angle: Once defined by action and honor, he must now grapple with stillness, humility, and the terror of being forgotten.

Twist(s): By spring, his leg mends, but his will to fight does not. The scar becomes a mark of renunciation, not valor.

The Color Beneath the Scar

Genre: Contemporary Literary Fiction

Plot Idea: A young woman undergoes skin graft surgery after a car accident. As her body heals, she struggles to reconcile the face in the mirror with the one she remembers.

Character Angle: Her journey isn’t about regaining beauty; it’s about reclaiming ownership of her body and identity.

Twist(s): When she meets another survivor with visible scars, she learns healing isn’t about hiding, it’s about connection.

Stitches of Gold

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A healer uses enchanted golden thread to sew wounds that close instantly, but each stitch transfers a fraction of the injury’s pain into her own body.

Character Angle: As her own body deteriorates, she must decide which lives are worth saving and which are worth letting go.

Twist(s): Her scars glow faintly, revealing a celestial map, each healed soul a star that now burns in her skin.

The Surgeon’s Mark

Genre: Historical / Medical Drama (19th Century)

Plot Idea: A pioneering surgeon attempts one of the first antiseptic amputations, but his patient’s infection forces him to confront the limits of his knowledge.

Character Angle: Driven by scientific progress, he’s haunted by every scar he leaves behind, literal signatures of imperfection.

Twist(s): His journals of failures later became the foundation of modern surgical practice. His shame becomes medicine’s salvation.

Echoes Under the Skin

Genre: Science Fiction / Psychological Thriller

Plot Idea: After a spacecraft crash, survivors are treated with regenerative nanotech that heals their bodies perfectly, but every healed wound triggers vivid, intrusive memories of the trauma.

Character Angle: The protagonist begins self-harming to test whether pain or the memories are more real.

Twist(s): The nanotech isn’t healing; it’s archiving human experience to preserve data for an alien species.

The Weaver of Flesh

Genre: Dark Fantasy

Plot Idea: In a kingdom where scars determine social rank, a disgraced healer discovers a forbidden herb that can erase them at the cost of memory.

Character Angle: Torn between compassion and ambition, she secretly sells the treatment to nobles while her own scars remain untouched as penance.

Twist(s): When her lover erases all memory of their relationship to join the nobility, she realizes she’s sold away more than flesh – she’s rewritten history.

Splintered Grace

Genre: Contemporary Christian Fiction / Drama

Plot Idea: A missionary injured in an earthquake faces a year of recovery in physical therapy, where she must confront her faith, frustration, and pride.

Character Angle: She learns grace not from miracles, but from the long, patient process of healing.

Twist(s): The man who saves her life later dies in the same hospital, forcing her to redefine what “healing” truly means.

Iron Petals

Genre: Steampunk Romance

Plot Idea: A clockmaker with a prosthetic hand of his own design hides his injury from society. When he meets a botanist experimenting with living metal, he’s drawn into her dream of merging art and anatomy.

Character Angle: His scars represent shame and failure, but she sees beauty in imperfection.

Twist(s): When her experiment goes wrong, he must rebuild her body as she once healed his heart, proving that healing is mutual creation, not restoration.

The Scar Map

Genre: Fantasy Adventure

Plot Idea: A thief discovers his scars form a map to an ancient vault. The marks appeared after being healed by a mysterious cleric years ago.

Character Angle: Scarred from both wounds and guilt, he’s forced to confront the literal and emotional geography of his past.

Twist(s): The vault holds no treasure, only the memories of everyone the cleric ever healed. Each scar he bears is a piece of another’s pain.

Fracture Point

Genre: Science Fiction / Medical Mystery

Plot Idea: In a world where bone regeneration is instant, a researcher investigates why a small percentage of people don’t heal and instead become stronger.

Character Angle: As one of the “non-healers,” she discovers her fractures create crystalline structures inside her skeleton that resist aging.

Twist(s): Her condition isn’t evolution. It’s the body’s rebellion against synthetic perfection.

The Painter of Scars

Genre: Historical Fantasy (Renaissance Italy)

Plot Idea: A disfigured painter uses alchemical pigments that can disguise scars when painted directly onto the skin. Nobles seek his art, but the paint bonds to their blood, sharing emotions between artist and subject.

Character Angle: Lonely and bitter, he experiences the pain and vanity of his patrons through their living portraits.

Twist(s): His masterpiece – a portrait of a saint – heals the scars of everyone who views it but consumes his own life as the price.

After the Fire

Genre: Contemporary Drama / Romance

Plot Idea: A firefighter who barely survives a building collapse spends months recovering from burns. Haunted by guilt and scarred beyond recognition, he pushes everyone away, including the woman who saved him.

Character Angle: His scars are both shield and prison. Through volunteer work at a burn recovery center, he helps others reclaim their confidence before he reclaims his own.

Twist(s): The woman he’s been mentoring online through the center’s support forum is his rescuer, and she bears scars of her own.

When writing recovery, don’t rush it. A believable timeline grounds even the most fantastical story. A knight who limps for weeks after a broken leg, or a soldier who fears fire long after his burns heal, feels more human than one who shrugs off agony.

Healing – physical and emotional – isn’t a return to normal. It’s adaptation. Every scar, every ache, every tremor tells a story about survival. Let your readers feel not just the pain of your characters’ injuries, but the strength it takes to live with what comes after.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

The Writer’s Guide to Healing Herbs and Other Treatments

Posted on January 16, 2026 Leave a Comment

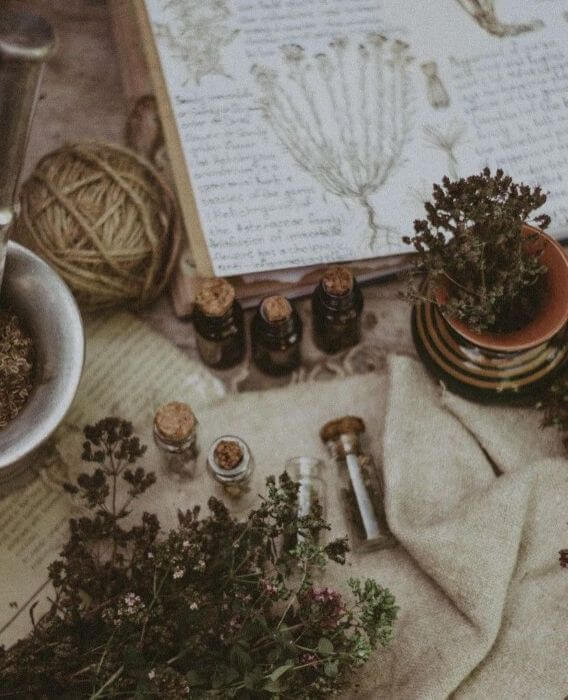

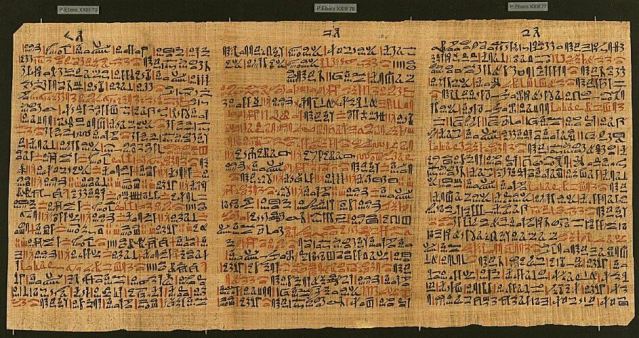

Before antiseptics, antibiotics, and modern surgery, healers relied on the natural world to treat wounds and illnesses. Herbs, roots, resins, and animal products formed the foundation of medicine from ancient Egypt through the 19th century, and they still appear in fantasy, historical, and even post-apocalyptic fiction. When written accurately, herbal medicine can lend authenticity to your world-building and depth to your characters, showing how they interact with the limits of their time.

Understanding Herbal Medicine

For most of history, medicine was based on observation and tradition, not scientific testing. Some remedies genuinely helped, others worked by coincidence or placebo, and some were outright harmful.

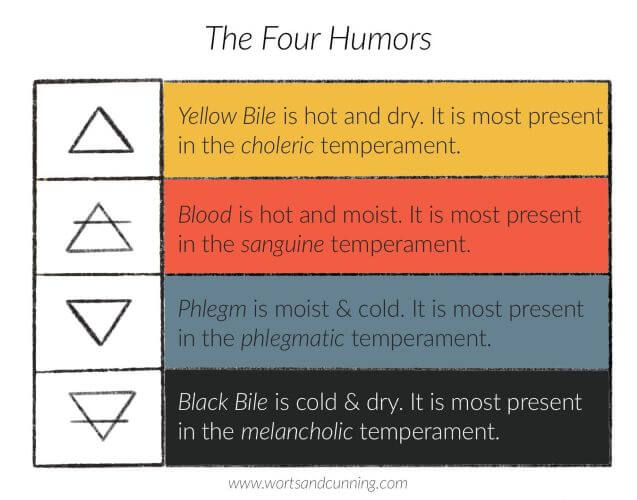

The ancient and medieval world believed in the theory of humors: that health depended on balancing four fluids: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. Illness came from imbalance, and treatments aimed to restore equilibrium through purging, bloodletting, or balancing “hot” and “cold” herbs.

While the humoral theory was incorrect, many of the herbs used in those treatments had real medicinal properties and modern medicine still uses compounds derived from them today.

Herbal Preparations

Writers often confuse teas with tinctures or poultices. Here’s a quick guide to keep your herbal realism on point.

Infusion (Tea)

Extraction using hot water.

Pour boiling water over herbs, steep, and strain.

Gentle internal treatments (digestion, relaxation).

Decoction

Stronger water-based extraction using boiling.

Boil roots, bark, or tough herbs 10–30 min.

Used for fever, pain, or energy restoration.

Tincture

Alcohol-based extract preserving active compounds.

Soak herbs in alcohol or vinegar for weeks.

Concentrated medicine, small doses for long-term use.

Poultice

Warm, moist mass of crushed herbs applied directly to skin.

Mash herbs and apply them to wounds or sprains.

Draws out infection, soothes inflammation.

Salve/Ointment

Oil- or fat-based preparation.

Infuse herbs in oil, mix with beeswax.

Protects wounds, moisturizes skin.

Liniment

Liquid rubbed into skin for sore muscles or joints.

Mix herbs with alcohol, vinegar, or oil base.

Pain relief, muscle stiffness.

Syrup

Sweet medicinal solution.

Combine herbal decoction with sugar or honey.

Masks bitter herbs; used for coughs or children.

Common Historical and Fantasy-Friendly Remedies

Honey

Use: Applied to wounds, burns, and infections.

Preparation: Used raw or mixed with herbs; sometimes spread on linen dressings.

Scientific Value: Honey is antibacterial and antifungal because of its acidity, hydrogen peroxide content, and ability to draw out moisture from bacteria.

Usefulness: Legitimate. Modern medicine still uses medical-grade honey (especially Manuka honey) for burn and wound treatment.

Garlic

Use: Antiseptic, used in poultices and tonics.

Preparation: Crushed and applied to wounds or eaten to “purify the blood.”

Scientific Value: Contains allicin, a real antibacterial compound.

Usefulness: Effective in mild antibacterial and antifungal applications; overuse may irritate skin or stomach.

Willow Bark

Use: Pain relief, fever reduction.

Preparation: Brewed as tea or chewed raw.

Scientific Value: Contains salicin, precursor to aspirin.

Usefulness: Highly effective, one of history’s most successful herbal remedies.

Aloe Vera

Use: Soothes burns, skin irritations, and wounds.

Preparation: Gel from the fresh plant applied topically.

Scientific Value: Proven to reduce inflammation and aid healing.

Usefulness: Safe and effective, still used today.

Lavender and Chamomile

Use: Calm nerves, promote sleep, and soothe pain.

Preparation: Infused in teas, oils, or poultices.

Scientific Value: Mild sedatives; lavender oil also has antibacterial effects.

Usefulness: Genuinely soothing; effective for mild anxiety or insomnia.

Comfrey (also known as “Knitbone”)

Use: To help broken bones, bruises, and wounds heal faster.

Preparation: Made into poultices or ointments.

Scientific Value: Contains allantoin, which encourages cell growth but also toxic alkaloids if ingested.

Usefulness: Safe for topical use on unbroken skin; effective for bruises and sprains but potentially harmful internally.

Yarrow

Use: Stops bleeding and reduces inflammation.

Preparation: Leaves crushed or made into poultices, tinctures, or teas.

Scientific Value: Antimicrobial and astringent properties verified.

Usefulness: Effective as a mild antiseptic; “soldier’s woundwort” in several cultures for good reason.

Elderflower and Echinacea

Use: Colds, fevers, and immune support.

Preparation: Brewed as teas or tinctures.

Scientific Value: Mild immune-modulating and anti-inflammatory effects.

Usefulness: Helpful for mild infections or inflammation, though not a cure-all.

Foxglove (Digitalis)

Use: Historically for heart ailments.

Preparation: Powdered or steeped leaves (dangerous without dose control).

Scientific Value: Contains digitalin, used in modern heart medicine.

Usefulness: Effective in minute doses, deadly in large ones. Excellent for dramatic fiction but risky.

The Usefulness (and Limits) of Herbal Medicine

What Worked

Many herbal treatments have measurable pharmacological effects: pain relief (willow), antibacterial action (honey, garlic), calming (lavender, chamomile), and skin healing (aloe).

They provided comfort and care when modern medicine didn’t exist.

What Didn’t

Humoral theory: The belief that balancing hot/cold, wet/dry humors could cure illness was false.

Lack of sterility: Contaminated bandages and tools often caused more harm than help.

Guesswork in dosing: Effective herbs (like foxglove or hemlock) could kill without precise measurement.

Superstition: Magical thinking sometimes replaced genuine care.

In fiction, a healer’s herbal craft can show intelligence, empathy, and cultural depth, even when she doesn’t understand the science behind her remedies. A few accurate herbs and preparations go a long way toward world-building realism.

Remember: in many settings, belief in the treatment mattered as much as the treatment itself.

For Fantasy and Historical Fiction

Blend real herbs with invented ones to expand your world organically (“moonleaf” with antiseptic glow, “ironroot” for bone healing). Consider scarcity. Some herbs may grow only in specific regions, making them valuable plot elements.

In worlds with magic, healing herbs may amplify or stabilize spell work rather than replace it.

Example: A healer brews an infusion of yarrow and comfrey to treat a soldier’s wound, then adds a drop of phoenix ash to awaken the herbs’ dormant magic. The result heals flesh but scars the soul, an ancient trade-off forgotten by most.

For Science Fiction Writers

Herbal medicine might experience a renaissance on colony worlds where modern pharmaceuticals are scarce. Genetic engineering or biofabrication could resurrect extinct medicinal plants or create new hybrids. Alien botanicals may function unpredictably: a flower that heals humans but poisons androids, or vice versa. “Traditional medicine” might coexist with AI diagnostics, creating tension between human intuition and machine precision.

Healing Herbs and Medicine Through History

North and South America

Medical History

Indigenous nations across the Americas developed rich botanical systems long before European contact, each adapted to local ecosystems. Knowledge was empirical and spiritual: plants were seen as gifts with both physical and sacred power. After colonization, European and Native traditions blended into folk medicine and later informed modern pharmacology.

Notable Practices and People

Aztec Codex Badianus (1552): one of the earliest herbal manuscripts of the Americas.

Maya and Inca healers: used observation and ritual cleansing to restore balance.

Modern ethnobotany owes much to the documentation of Indigenous herbalists.

Characteristic Remedies

North America: Willow bark, echinacea, goldenseal, yarrow, sage, cedar smoke. Willow bark contains salicin (natural aspirin). Sage and cedar for purification and mild antisepsis.

Central America: Aloe vera, cacao, chili, agave sap, copal resin. Chili for circulation; cacao for heart health; copal burned in cleansing rituals.

South America: Cinchona bark, guarana, yerba mate, coca leaf, dragon’s blood resin (Croton lechleri) Cinchona contains quinine (anti-malaria); coca leaves as a mild stimulant; dragon’s blood aids wound healing.

Europe

Medical History

Rooted in Greek and Roman humoral medicine; later fused with monastic herbalism and Renaissance science. Medicine developed from Galen’s theory of humors to Paracelsus’s chemical model and eventually to anatomy and germ theory.

Notable Works and Figures

Hippocrates (5th c. BCE): Corpus Hippocraticum: “first do no harm.”

Galen (2nd c. CE): codified humoral theory.

Dioscorides (1st c. CE): De Materia Medica—Europe’s definitive herbal for 1,500 years.

Hildegard of Bingen (12th c.): monastic healer, integrated herbs with theology.

Paracelsus (16th c.): introduced chemical medicine.

Pasteur and Lister (19th c.): germ theory and antisepsis revolutionized care.

Characteristic Remedies

Classical: Willow, garlic, mint, thyme, opium poppy Foundations of Western pharmacology.

Medieval Monastic: Chamomile, lavender, rosemary, sage, valerian, honey. Cultivated in cloister gardens; used for digestion, sleep, and wound care.

Folk Europe: Comfrey, elderflower, foxglove, St John’s wort, yarrow. Many still used; foxglove/digitalis (heart drug).

Africa

Medical History

Healing intertwined with community ritual, divination, and empirical herbal knowledge. Egyptian medicine (3rd millennium BCE) left the earliest written surgical and pharmacological records. Sub-Saharan traditions emphasized holistic healing: spiritual, physical, and social balance.

Notable Works and Figures

Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE): lists 700+ remedies including honey, resin, and castor oil.

Imhotep (27th c. BCE): physician-architect later deified.

Modern ethnobotany: research in Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa continues to validate many ancient remedies.

Characteristic Remedies

Egypt / North Africa: Honey, frankincense, myrrh, castor oil, aloe vera. Antimicrobial resins and soothing oils.

West Africa: Neem, hibiscus, baobab fruit, bitter leaf, kola nut. Antimalarial and antioxidant properties.

East / South Africa: Rooibos, buchu, devil’s claw, African potato (Hypoxis). Anti-inflammatory and tonic uses; some proven pharmacologically.

Middle East

Medical History

Birthplace of Greco-Arab (Unani) medicine blending Greek, Persian, and Indian thought. Hospitals and medical schools flourished under the Abbasids; scholars preserved and expanded classical texts.

Notable Works and Figures

Avicenna (Ibn Sina, 980–1037): The Canon of Medicine, a standard text in Europe for 600 years.

Rhazes (Al-Razi): wrote on smallpox and measles; championed empirical observation.

Al-Zahrawi: surgical pioneer; developed cauterization tools.

Characteristic Remedies

Black seed (Nigella sativa): “Cure for everything but death,” mild antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory.

Dates, figs, honey, olive oil: Nutrient-dense foods as medicine.

Myrrh and frankincense: Disinfectant, wound dressing, incense for ritual purification.

Saffron, turmeric, cardamom, cinnamon: Digestive and mood-lifting properties; key in humoral balance.

Asia

Medical History

Asia developed multiple complex medical systems independently: Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), Ayurveda (India), kampo (Japan), Tibetan, Korean, and Southeast Asian blends.

All emphasize balance (yin/yang or doshas) and prevention through diet, herbs, and movement.

Notable Works and Figures

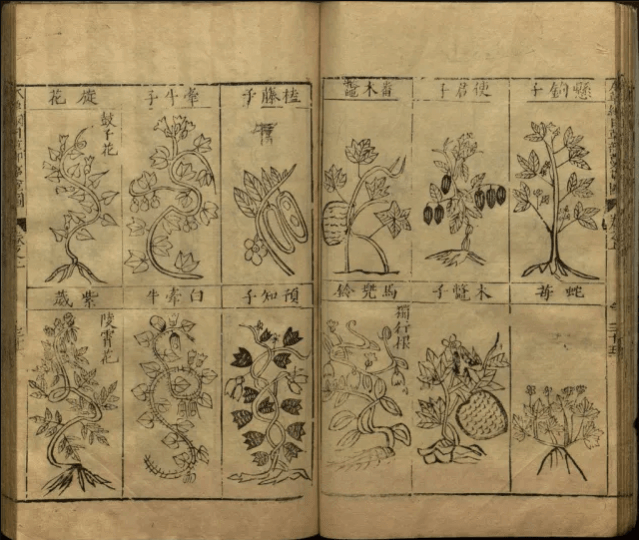

Shennong Bencao Jing (c. 200 CE, China): earliest systematic herbal.

Li Shizhen’s Bencao Gangmu (1596): 1,800 herbs classified.

Charaka Samhita and Sushruta Samhita (India): foundational Ayurvedic texts; Sushruta described surgical techniques including plastic surgery.

Characteristic Remedies

China: Ginseng, ginger, licorice root, goji berries, honeysuckle, rhubarb, mugwort (moxa). Tonics for energy, digestion, immunity.

India (Ayurveda): Turmeric, ashwagandha, holy basil (tulsi), neem, gotu kola, triphalā. Anti-inflammatory, adaptogenic, rejuvenating.

Japan / Korea: Green tea, shiitake, reishi, ginseng, shiso. Immune and metabolic support.

SE Asia: Lemongrass, galangal, tamarind, betel leaf. Digestive, antiseptic, and aromatic therapies.

Australia and New Zealand

Medical History

Aboriginal and Māori peoples cultivated deep botanical knowledge suited to extreme climates. Healing was inseparable from spirituality, illness arose from imbalance between person, land, and ancestor spirits. European colonization suppressed but did not erase these traditions.

Characteristic Remedies

Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia): Antiseptic for cuts, infections. Modern studies confirm antimicrobial oils.

Eucalyptus: Decongestant, antiseptic vapor. Now a base for cough lozenges and balms.

Kakadu plum: Extremely high vitamin C; immune support. Studied for antioxidant properties.

Manuka honey (NZ): Wound healing. Medical-grade form clinically proven antibacterial.

Emu oil: Anti-inflammatory rub. Still used for muscle and joint pain.

Modern Integration

Today Australian and New Zealand research merges traditional Aboriginal, Māori, and Western medicine, focusing on bio-active native plants and respectful collaboration with Indigenous knowledge holders.

For Writers

Choose herbs appropriate to climate and trade routes: Show how healers obtain them.

Let philosophy shape treatment: an Ayurvedic healer balances doshas, a Greek physician purges humors, an Indigenous shaman restores spiritual harmony.

Show mixtures of success and failure: realism often lies where belief outpaces science.

Use genuine substances (honey, willow, turmeric) to ground fantastical cures in believable tradition.

Depicting Healing Herbs and Natural Treatments Across Genres

Herbs, tonics, and natural remedies appear in nearly every genre: from medieval monasteries to futuristic bio-labs. But the way they’re understood, used, and valued depends entirely on the world around them. A 14th-century herbalist, a modern naturopath, and a starship botanist might all reach for the same plant but for completely different reasons.

Contemporary Fiction

Modern readers live in a world of science-based medicine but remain fascinated by holistic or “natural” care. Herbal treatments often appear alongside or in tension with modern pharmaceuticals.

How to Depict Herbs Today

Focus on integration rather than opposition: characters might use chamomile for sleep while on prescribed anxiety medication, or honey to soothe wounds alongside antibiotic cream.

Show awareness of dosage, regulation, and skepticism. Today’s readers expect realism and a distinction between proven benefits and folklore.

Herbalism can reveal personality and culture: a grandmother’s remedy connects generations, while a scientist protagonist tests traditional cures under a microscope.

Include modern preparations: capsules, teas, essential oils, or extracts rather than crude poultices.

Story Function

Reflects character values (naturalist vs. rationalist). Represents cultural identity or intergenerational wisdom. Serves as a metaphor for healing that’s emotional as well as physical.

Example: A medical student dismisses her grandmother’s traditional remedies until a honey-and-herb salve from her village outperforms a commercial antiseptic in a rural clinic.

Historical Fiction

Before germ theory, medicine was trial, error, and tradition. Herbs were the only accessible treatments, and healing was often a mixture of faith, superstition, and genuine skill.

How to Depict Herbs Historically

Use plants accurate for the region and era: monks in England grew sage and valerian; Arab physicians used black seed and saffron.

Tie remedies to the theory of humors or local belief systems: a “hot” herb to balance “cold phlegm,” or a ritual blessing before applying a poultice.

Show the risk of infection and contamination, even effective herbs were applied with unsterilized hands or reused cloth.

Characters might not know why something works, only that it does. This limited understanding can create tension between healer and patient.

Story Function

Highlights the limitations and ingenuity of the past. Reveals the character’s worldview (rational herbalist vs. superstitious villager). Provides atmosphere: jars of dried herbs, smoky apothecaries, fragrant oils, and candlelit infirmaries.

Example: A 14th-century midwife uses rosemary, yarrow, and honey to save a noblewoman’s childbed fever, earning praise until the local priest accuses her of witchcraft for meddling in “God’s will.”

Fantasy

Fantasy gives writers the freedom to blend real-world herbalism with the supernatural. Herbs may carry magical properties, spiritual resonance, or hidden costs.

How to Depict Herbs in Fantasy

Ground the magic in reality: base your fictional herbs on real ones, e.g., comfrey-inspired bonebind, willow-like painleaf, or glowing moonwort that heals but drains stamina.

Make herbal knowledge cultural and practical: a dwarven miner might use lichen for lung protection; elves might brew luminous teas to restore mana.

Use herbs as magical catalysts or stabilizers, required ingredients for healing spells or potions.

Establish rules and scarcity: not every herb grows everywhere, and improper mixing could poison rather than heal.

Story Function

Enhances world-building: flora becomes part of culture, economy, and warfare. Tests the limits of magic. Does it replace herbs or rely on them? Symbolizes harmony with nature or the loss of it.

Example: A healer’s apprentice learns that her mentor’s potent healing salve works only when mixed with her own blood, revealing the herb’s magic binds to life essence, not its leaves.

Science Fiction

Science fiction reimagines herbs through biology, chemistry, and technology. Natural compounds can become advanced pharmaceuticals, or alien flora can reshape our concept of medicine altogether.

How to Depict Herbs in Sci-Fi

Future pharmacology: herbal compounds rediscovered as sources for lab-synthesized drugs.

Genetic engineering: plants modified to grow faster, produce targeted antibiotics, or adapt to new worlds.

Alien ecosystems: vegetation that heals one species but harms another; symbiotic organisms that act as living medicine.

Cultural contrast: a frontier colony depends on herbal treatments after supply-chain collapse, rediscovering ancient remedies.

Story Function

Raises ethical questions: who owns the genetic rights to a miracle plant? Explores survival and adaptation: when high-tech fails, nature endures.

Merges spirituality and science: botanists treating alien plants as both sacred and scientific wonders.

Example: On a terraformed planet, colonists cultivate a native moss that speeds up cellular repair. Decades later, they learn the moss heals by integrating its DNA into theirs, turning them slowly into hybrids.

Plot and Character Ideas

The Last Apothecary’s Daughter

Genre: Historical Fiction (17th Century)

Plot Idea: After her father’s death, a young apothecary’s daughter continues his herbal practice in secret during England’s witch trial hysteria. When a noblewoman’s son falls ill, she must risk exposure to save him.

Character Angle: Intelligent but fearful, she struggles to separate her father’s science from her society’s superstition.

Twist(s): The physician who accused her of witchcraft to eliminate competition intentionally caused the boy’s illness.

Bitterroot Remedy

Genre: Contemporary Drama

Plot Idea: A burned-out pharmacist in Montana rediscovers her passion for healing after meeting a Native herbalist who teaches her traditional plant medicine.

Character Angle: Rational to a fault, she’s skeptical of anything not backed by lab data, but chronic pain forces her to try what science can’t explain.

Twist(s): Her pharmacy chain tries to buy and patent the herbalist’s recipes, and she must choose between career and conscience.

The Poisoner’s Apprentice

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A young healer is apprenticed to a royal herbalist whose remedies are also deadly poisons depending on dosage. When the king is poisoned, suspicion falls on her.

Character Angle: Naïve but quick-witted, she must navigate palace intrigue armed only with her master’s coded herbal journals.

Twist(s): The poison that killed the king is her own creation, altered in secret by someone she trusted.

Garden of the Moon Priestess

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: In a world where plants glow with lunar energy, a priestess who tends the sacred gardens must save her people when the moon’s light fades.

Character Angle: Her faith is shaken as every cure she brews fails until she realizes the plants’ power responds not to prayer but emotion.

Twist(s): The withering garden reflects her own grief; healing the plants requires confronting the loss she’s denied.

The Fever Tree

Genre: Historical Adventure (19th Century Africa)

Plot Idea: A British botanist searching for the legendary “fever tree” (source of quinine) partners with a local healer who already knows its secret but not the greed it will unleash.

Character Angle: Idealistic about discovery, he learns the cost of “progress” when his research threatened to exploit the very people he depends on.

Twist(s): The fever tree exists, but it’s symbiotic with a fungus that dies in captivity, dooming any attempt to mass-produce it.

The Herbalist of Ironvale

Genre: Steampunk Fantasy

Plot Idea: In a smog-choked industrial city, a self-taught herbalist treats miners poisoned by factory runoff until a powerful guild accuses her of sabotaging progress.

Character Angle: Tough and resourceful, she’s haunted by a past as a factory nurse who ignored early victims.

Twist(s): The city’s pollution is creating new, mutagenic herbs underground, plants that could both cure and kill.

Code Green

Genre: Science Fiction / Eco-Thriller

Plot Idea: On a dying Earth, a bioengineer discovers an ancient plant in the Amazon that can cleanse air toxins, but its pollen may be dangerously addictive.

Character Angle: Struggling between ecological salvation and ethical restraint, she hides her research from corporate backers hungry for control.

Twist(s): The plant is sentient and begins communicating through dreams, urging her to destroy all human industry.

The Apothecary’s Ledger

Genre: Historical Mystery (18th Century)

Plot Idea: A London apothecary’s detailed patient ledger becomes the key to solving a string of suspicious deaths among society’s elite.

Character Angle: A widowed bookseller inherits the ledger and is drawn into the web of secrets it records.

Twist(s): The apothecary was blackmailing patients with knowledge of their ailments, and the killer is one of his “cures.”

Wild Honey

Genre: Contemporary Romance / Healing Drama

Plot Idea: A war veteran with PTSD returns home to run his late grandfather’s bee farm. A local herbalist helps him rediscover purpose as they create healing salves from honey and wild herbs.

Character Angle: Quiet and guilt-ridden, he struggles to believe he deserves peace.

Twist(s): The honey from one hive contains a rare antibacterial compound that could revolutionize medicine, but selling it would destroy the land that healed him.

The Saffron Conspiracy

Genre: Political Thriller

Plot Idea: In the near future, a spice genetically engineered to cure heart disease becomes the world’s most valuable resource. A botanist-turned-smuggler tries to keep it from being monopolized by pharmaceutical giants.

Character Angle: Formerly idealistic, she’s haunted by her role in creating the monopoly she now fights against.

Twist(s): The “saffron cure” only works if grown in native soil, making the poorest farmers the key to the planet’s survival.

The Healer of Red River

Genre: Historical Western

Plot Idea: A former Civil War nurse opens a frontier clinic, using Native and folk remedies to treat settlers and Indigenous patients alike, drawing suspicion from both communities.

Character Angle: Pragmatic yet empathetic, she values results over politics, walking a moral tightrope.

Twist(s): Her secret ingredient – black willow – becomes the first formulation of aspirin, years before it’s patented.

Seeds of the Stars

Genre: Science Fiction

Plot Idea: A deep-space botanist aboard a generational ship tends a collection of ancient Earth plants. When a mysterious plague infects the crew, she discovers the cure hidden in her forgotten garden.

Character Angle: Isolated and dismissed as obsolete, she finds renewed purpose as humanity’s last healer.

Twist(s): The cure isn’t a plant, it’s a symbiotic spore that will alter human DNA forever, making them part-plant to survive alien worlds.

Healing herbs have always balanced hope and harm, bridging faith, nature, and early science. Whether your healer is a medieval apothecary, a fantasy herbalist, or a space botanist, grounding their knowledge in real principles like antiseptic honey or willow bark pain relief adds authenticity.

Remember: not every cure needs to work perfectly. Sometimes, the struggle to heal with limited tools makes a character and a story feel most human.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

The Writer’s Guide to the Long-term Effects of Injuries

Posted on January 2, 2026 Leave a Comment

When a character survives an injury in fiction, that’s often where the story ends. The hero limps off into the sunset or awakens in a hospital bed, battered but triumphant. Yet for real people, recovery doesn’t stop when the bleeding does. It continues for months or years afterward.

The long-term effects of injury – chronic pain, fatigue, mobility limitations, and psychological adjustment – offer rich opportunities for character depth, realism, and emotional stakes. Portraying them accurately can turn a one-dimensional hero into a living, breathing survivor.

What Happens After “Healing”?

Even when bones knit, tendons reattach, or skin scars over, the body doesn’t always return to what it was before. Pain, stiffness, and weakness can linger long after the visible wound is gone. The severity, type, and location of the injury determine what kind of long-term impact your character lives with.

Chronic Pain: The Lingering Companion

Pain that persists for months or years after the initial injury has healed. It may stem from nerve damage, scar tissue, or chronic inflammation.

How It Feels

Constant dull ache or sharp shooting pain.

Weather sensitivity (worse in cold or damp conditions).

Random flare-ups that strike without warning.

Sleep disruption, irritability, and exhaustion.

Writing Tips

Chronic pain fluctuates. Some days are manageable, others unbearable.

Show adaptation: careful movements, altered gait, habitual stretching, grimaces.

Use internalization: pain erodes patience and focus, making simple tasks monumental.

Example: A retired knight massages his shoulder each morning before strapping on armor, knowing the old wound will ache by noon but doing it anyway because duty demands it.

Energy Levels and Fatigue

Healing consumes energy. Chronic pain, inflammation, or nerve damage can leave a body constantly exhausted. Pain meds, depression, or lack of restorative sleep compound it.

How It Appears

Struggling to concentrate.

Taking frequent breaks.

Sleeping long hours but never feeling rested.

Short temper or zoning out mid-conversation.

Writing Tips

Fatigue reshapes daily life: errands take twice as long, plans get canceled, and guilt sets in.

Show characters learning their limits: pacing themselves, conserving energy (“spoon theory” for chronic illness is a useful reference).

Example: A once tireless ranger now times every movement; scaling a small hill takes strategy, not strength. He saves energy for the moments that count.

Mobility and Physical Adaptation

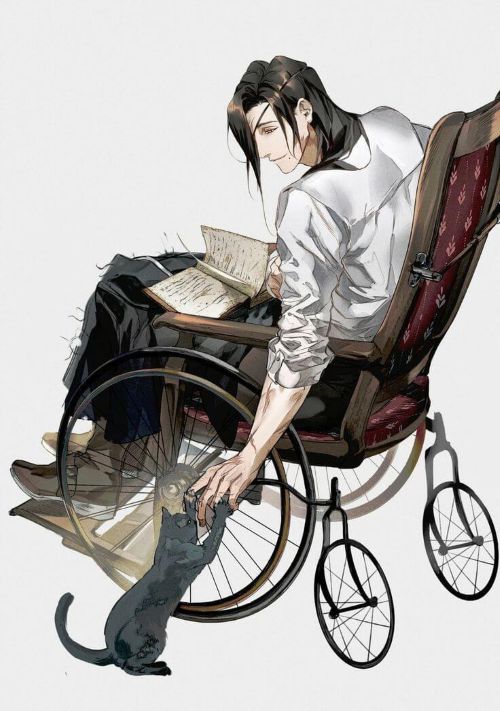

Varying Severity

Mild: Occasional stiffness or slight limp.

Moderate: Requires cane, brace, or regular rest.

Severe: Wheelchair, prosthetic, or total loss of function.

Challenges

Navigating stairs, terrain, or uneven ground.

Carrying items while using mobility aids.

Pain or fatigue triggered by overexertion.

Emotional and Social Coping

Common Reactions

Frustration and grief over lost abilities.

Anxiety about dependence or burdening others.

Changes in self-image or identity.

Isolation if others underestimate or pity them.

Positive Coping

Finding new purpose or adapting old skills.

Humor as resilience.

Supportive relationships and community.

Unhealthy Coping

Overcompensation, denial, or self-neglect.

Substance abuse or isolation.

Internalized shame or bitterness.

Writing Tips

Recovery isn’t linear: your character might alternate between acceptance and despair.

Use relationships to reflect healing: friends who understand vs. those who don’t.

Avoid the “magical recovery” trope unless there’s a strong worldbuilding reason.

Research lived experiences. Look for blogs, interviews, or memoirs from people with similar injuries.

Focus on sensory detail. Pain isn’t generic. Describe its rhythm, texture, and emotional echo.

Don’t rush the timeline. Physical recovery can take years, and emotional recovery often longer.

Show adaptation over inspiration. Readers connect more deeply when resilience feels practical, not saintly.

Weave in humor and normalcy. Even in chronic pain, people laugh, love, and build lives.

Show realistic adjustments: sitting to work, altering fighting styles, building routines around accessibility.

Avoid framing disability as tragedy or inspiration alone. Show it as life, with humor, frustration, and adaptation.

Remember: mobility aids are tools of independence, not symbols of defeat.

Examples

A modern soldier with a spinal injury learns to navigate civilian life, finding new purpose training service dogs.

A medieval blacksmith with a crushed hand crafts one final masterpiece: a prosthetic tool that lets him forge again.

A space pilot with a nerve injury must rely on an AI co-pilot but struggles to trust the machine that replaced his instincts.

A fantasy archer loses mobility after a cursed wound; her solution is to bond with a magical hawk who becomes her eyes and hands in battle.

Depicting the Long-Term Effects of Injuries Across Genres

The aftermath of injury doesn’t end when the bleeding stops. Whether your story is set in a modern hospital, a medieval battlefield, or a starship far from home, the long-term effects (pain, fatigue, and adaptation) will shape both your characters and your world. How those effects are perceived, managed, and narrated depends heavily on genre and setting.

Contemporary Fiction

How They Occur

Car crashes, workplace accidents, sports injuries, chronic illnesses, and military wounds.

Injuries caused by trauma, violence, or medical complications (burns, amputations, spinal damage).

Depiction Notes

Modern readers expect realism: accurate recovery timelines, physical therapy, medical management, and social implications (insurance, accessibility, stigma).

Chronic pain and fatigue are invisible to outsiders. Characters may face disbelief or dismissal (“But you look fine”).

Mobility aids, prosthetics, and adaptive technology are normalized but can still carry emotional weight.

Social Dynamics

Support networks (family, partners, therapy, online communities) help recovery but can also create dependency conflicts.

Some characters hide their pain to maintain independence; others overcompensate through work or perfectionism.

Narrative Use

Focus on how the injury reshapes daily life and identity.

Depict moments of quiet endurance rather than melodrama: choosing an elevator over stairs, canceling plans on flare-up days, laughing through frustration.

Example: A marathon runner learning to live with a prosthetic leg discovers that recovery isn’t just physical, it’s learning to accept help and redefine what “strong” means.

Historical Fiction

How They Occur

War injuries (sword cuts, cannon blasts, burns).

Labor accidents, riding falls, childbirth injuries, infections, amputations.

Depiction Notes

Limited medical care means many injuries lead to permanent impairment.

Crude prosthetics, untreated nerve damage, and infection create lifelong complications.

Chronic pain and fatigue are common, though rarely diagnosed as such.

Social Dynamics

Disability is often tied to moral, spiritual, or class-based ideas:

A “crippled” soldier may be seen as brave yet pitiful.

A laborer unable to work becomes a financial burden.

A noblewoman’s limp might be hidden to preserve marriage prospects.

Religious or superstitious interpretations abound: pain as divine punishment, suffering as penance, or miraculous survival as proof of favor.

Narrative Use

Injuries can become metaphors for societal change: the broken knight who symbolizes the cost of endless war, the midwife who continues her work despite her own damage.

Emphasize adaptation within limitation: crafting new tools, relying on community, or finding purpose beyond physical labor.

Example: A wounded Napoleonic soldier returns home with a mangled arm. His struggle isn’t just physical, it’s surviving in a society that venerates heroes but forgets the maimed.

Fantasy

How They Occur

Battle wounds, magical injuries, curses, transformations, or long-term consequences of healing gone wrong.

Depiction Notes

Fantasy allows exploration of how magic intersects with recovery:

Healing spells may close wounds but leave nerve pain, stiffness, or magical “scars.”

Potions may suppress pain at the cost of addiction or side effects.

Divine healing could cure the body but not the mind, leaving lingering trauma.

The world’s culture shapes response: a limping warrior might be pitied in one kingdom and revered as blessed in another.

Social Dynamics

Magical prosthetics, enchanted braces, or sentient limbs could change what “disability” means.

Chronic pain might manifest as literal energy drain: fatigue that seeps magic or disrupts spellwork.

Supernatural coping mechanisms could mirror real-world ones: meditation becomes mana-balancing, herbal teas become enchanted tonics.

Narrative Use

Explore themes of power and loss: how a hero copes when magic can’t fix everything.

Healing magic’s limitations make the world feel grounded and morally complex.

Injuries can shape character development, turning warriors into teachers, or mages into philosophers.

Example: A battle mage, permanently weakened by a cursed burn, learns to wield quiet magic of restoration instead of destruction, becoming the mentor the next generation needs.

Science Fiction

How They Occur

Industrial accidents in colonies, space combat injuries, radiation exposure, neural or cybernetic trauma.

Depiction Notes

Medical technology can mitigate, but not erase, long-term effects:

Cybernetic prosthetics restore mobility but alter body image and identity.

Neural implants reduce pain but risk personality shifts or malfunction.

Cryogenic repair saves lives at the cost of lingering fatigue or sensory distortion.

Pain management might involve AI-monitored medication or nanobots that adjust neurotransmitters.

Social Dynamics

Disabilities might carry new social meanings: enhanced vs. unmodified, biological vs. mechanical.

Societies with instant healing tech may view unhealed characters as choosing to live with imperfection, a potential source of stigma or rebellion.

Narrative Use

Explore ethical questions: what happens when pain and weakness can be engineered out of existence?

Injury and augmentation can blur identity. What’s left of the “original” person when half the body is replaced?

Use the futuristic setting to parallel modern issues like accessibility, bodily autonomy, and chronic illness.

Example: A starship engineer with neural implants that suppress pain starts experiencing phantom sensations: memories of pain encoded in the circuitry itself.

Treatments for Long-Term Effects of Injuries Through History and Across Genres

How people treat long-term injuries reveals just as much about a society as how they fight their wars or heal their wounds. From herbal salves and superstition to physical therapy and neural implants, every era and world deals with chronic pain, fatigue, and mobility in its own way. But for your characters, the truest test isn’t whether their pain is cured, it’s how they live with what remains. Chronic injury and long-term effects remind readers that survival is never free; it’s an act of ongoing adaptation and strength.

Ancient Times

The concept of healing was deeply tied to religion and balance. Chronic pain and disability were often seen as divine punishment, fate, or imbalance of the body’s natural forces. Ancient physicians and healers understood that some injuries never truly healed and their remedies aimed to soothe, not cure.

Treatments

Herbal medicine: Willow bark (natural aspirin), opium poppy, and myrrh were used to dull pain.

Heat and massage: Egyptians and Greeks used hot stones, oils, and stretching for stiffness.

Hydrotherapy: Baths in sacred springs or mineral pools were believed to restore strength.

Religious and ritual healing: Offerings to Asclepius, prayers, charms, and amulets for divine intervention.

Narrative Insight

In an ancient setting, long-term pain might be viewed as a sacred mark (proof of surviving the gods’ test) or as a curse that isolates the character. Survival is a balance between endurance and faith.

The Middle Ages

Physical ailments were often seen as spiritual tests or punishments. Medicine relied on the theory of humors: balancing blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Chronic conditions were rarely differentiated from acute illness. If an injury didn’t heal, it was accepted as permanent.

Treatments

Poultices and salves: Honey, vinegar, and herbal pastes to ease inflammation.

Bloodletting and leeches: Used to “rebalance” the body.

Faith-based healing: Pilgrimages to shrines of saints, holy water, relics, and prayer circles.

Primitive mobility aids: Crude crutches, carved wooden canes, or slings.

Community care: Monasteries often provided long-term shelter and basic care for the disabled.

Narrative Insight

Pain and impairment might earn pity or suspicion of witchcraft or demonic influence. A maimed knight might retire to a monastery; a peasant might be left to beg. Writers can show resilience in characters who find new identity or purpose in a world with little sympathy.

18th and 19th Centuries

The Enlightenment introduced anatomy, surgery, and early rehabilitation. The Industrial Revolution increased accidents, creating awareness of “invalids” and long-term recovery. Medical science began to recognize pain management, though addiction and poor sanitation were rampant.

Treatments

Opioids and laudanum: Common painkillers prescribed freely, often leading to dependence.

Physical therapy: Began emerging in the late 19th century, often used for soldiers and accident victims.

Hydrotherapy and mineral spas: Popular “cures” for stiffness and exhaustion.

Prosthetics: Wooden limbs, iron braces, and early mechanical aids became more sophisticated after each war.

Rest cures: Long periods of enforced bed rest (especially for women), often worsening muscle loss and depression.

Narrative Insight

This era offers stark contrasts: mechanical innovation meets medical ignorance. A war veteran may have a crude prosthetic but no understanding of chronic pain; a Victorian lady may be sedated rather than treated. There’s rich opportunity to show how survival collides with social expectation.

Modern and Contemporary Medicine

The 20th and 21st centuries reframed chronic conditions as manageable rather than shameful. Medical care now recognizes the link between physical injury, chronic pain, and mental health.

Treatments

Pain management: Opioids (carefully monitored), NSAIDs, nerve blocks, acupuncture, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS).

Physical and occupational therapy: Strengthening, balance training, ergonomic tools.

Surgery: Joint replacements, nerve grafts, and advanced prosthetics.

Mental health support: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), mindfulness, trauma counseling.

Assistive technology: Wheelchairs, braces, adaptive software, prosthetic limbs with neural feedback.

Lifestyle management: Pacing, exercise, sleep regulation, and community support.

Narrative Insight

Modern characters can realistically live full, complex lives with chronic conditions, balancing independence and adaptation. The tension lies not in survival, but in perseverance, identity, and relationships.

Fantasy

Healing may be magical, alchemical, or divine but that doesn’t mean it’s perfect. A world’s magic system dictates whether long-term pain exists and if it does, why.

Treatments

Magical Healing: Instant regeneration spells might close wounds but leave “soul scars” or magical exhaustion. Healing potions suppress symptoms temporarily, with addiction or diminished effect over time.

Divine Intervention: Miracles granted only to the worthy or the wealthy create class tension and moral dilemmas.

Herbal Alchemy: Complex brews for pain relief, energy restoration, or muscle repair; side effects might include hallucinations or reduced magic power.

Runic or Elemental Therapy: Element-based treatments: heat from fire mages for stiffness, water mages restoring circulation, air mages easing breath and fatigue.

Narrative Insight

Fantasy allows exploration of cost and consequence: what if a hero refuses magical healing to retain humility? What if divine healers charge a soul debt for restoring mobility? Chronic pain in a magical world can serve as metaphor for inner scars and the limits of even great power.

Science Fiction

Future medicine may blur the line between human and machine. With gene editing, nanotechnology, and neural engineering, long-term effects might be treatable but at an ethical price.

Treatments

Cybernetic Prosthetics: Integrate with the nervous system for natural control but risk phantom feedback or identity crises.

Nanobot Repair Systems: Constantly monitor and mend tissue damage but require maintenance or AI oversight.

Neural Recalibration: Devices that regulate pain perception or energy but risk emotional blunting.

Cryogenic or Stem-Cell Regeneration: Regrows tissue but drains metabolic energy or ages other organs.

AI-Driven Rehabilitation: Personalized therapy delivered by synthetic caretakers, efficient but emotionally hollow.

Plot and Character Ideas

The Weight of Rain

Genre: Contemporary Drama

Plot Idea: A construction worker develops chronic back pain after an on-site accident and struggles to adjust to life behind a desk. His identity as a provider and “hands-on man” begins to crumble.

Character Angle: Stoic and practical, he hides his pain from his family, creating emotional distance just when they need him most.

Twist(s): When his teenage son joins the same company, the father must confront his pride and finally speak about what living in constant pain has cost him.

A Song for the Winter Sea

Genre: Historical Fiction (19th Century Whaling Era)

Plot Idea: A harpooner who loses his leg to a whale attack joins a ship as a sea shanty singer, using music to mask his pain and regain belonging among the crew.

Character Angle: His voice steadies the men at sea, but every storm reminds him of the scream he never uttered.

Twist(s): When a mutiny brews, his songs, once morale boosters, become coded messages to save loyal men from slaughter.

The Iron Dancer

Genre: Contemporary Romance

Plot Idea: A ballerina suffers a devastating ankle injury that ends her performance career. Forced into teaching, she must rediscover joy through others’ movement.

Character Angle: Obsessed with perfection, she measures her worth by grace until a student with cerebral palsy challenges her definition of beauty and movement.

Twist(s): The student’s unconventional dance wins international acclaim under her choreography, not her spotlight.

The Knight of the Broken Step

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A legendary knight survives a dragon’s flame but is left with a burned and weakened leg. Dismissed from service, he becomes a mentor to squires training for a war he can no longer fight.

Character Angle: He hides behind bitterness until his students face the same dragon and need his tactical mind, not his sword arm.

Twist(s): The dragon remembers him and spares the squires in recognition, turning his defeat into redemption.

Glass Nerves

Genre: Science Fiction / Cyberpunk

Plot Idea: A pilot fitted with cybernetic limbs after a crash begins experiencing phantom sensations – pain, cold, even “touch” – from the old flesh that’s gone.

Character Angle: Torn between gratitude for survival and horror at losing bodily autonomy, they begin to suspect the prosthetics’ neural interface records emotions.

Twist(s): The sensations aren’t memories, they’re feedback from someone else who used the same parts before.

The Seamstress of Ashfield Hall

Genre: Gothic Historical

Plot Idea: A governess badly burned in a house fire hides her scars beneath lace and high collars. As she teaches her employer’s daughter, whispers claim she was the fire’s cause.

Character Angle: Her physical pain mirrors her shame; she becomes obsessed with protecting the child to prove her worth.

Twist(s): The girl’s father was responsible for the blaze and has been using her disfigurement as his alibi.

Emberlight

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A fire mage loses control of his magic, permanently scorching his hands. Unable to cast safely, he apprentices under a healer who teaches him to channel warmth into restoration rather than destruction.

Character Angle: Once proud and feared, he wrestles with humility and fear of relapse.

Twist(s): His pain isn’t just physical. The burn itself stores unstable magic that could reignite under emotional stress.

The Cartographer’s Hand

Genre: Steampunk Adventure

Plot Idea: A famous mapmaker loses his dominant hand in an airship accident. Desperate to keep his reputation, he builds an intricate mechanical replacement.

Character Angle: His obsession with precision becomes literal. He cannot accept imperfection, even in his human heart.

Twist(s): The maps he draws with the mechanical hand reveal secret routes unseen by the human eye, possibly a connection between machine and otherworldly forces.

Beneath the White Noise

Genre: Contemporary Psychological Thriller

Plot Idea: After surviving an explosion, a journalist suffers from tinnitus and partial hearing loss. The constant ringing drives her to obsession as she investigates the incident.

Character Angle: Isolated from sound and sanity, she begins to hear patterns in the ringing, messages no one else can.

Twist(s): The sound is real: hidden transmissions from those responsible for the explosion.

The Weightless Soldier

Genre: Science Fiction / Military

Plot Idea: A paratrooper injured in atmospheric combat loses bone density due to zero-gravity recovery. Despite cybernetic reinforcement, he’s forbidden from re-deployment.

Character Angle: Built for battle but exiled to logistics, he must redefine purpose in a military that reveres strength.

Twist(s): When sabotage threatens his ship, his light frame, once a weakness, lets him navigate spaces others can’t, saving the crew.

The Singer and the Scar

Genre: Historical Fiction (WWI)

Plot Idea: A wartime nurse who inhaled mustard gas loses her voice but becomes a composer, transforming her pain into music that captures the soul of a generation.

Character Angle: Once the life of the ward, she now communicates through melody instead of words.

Twist(s): Her symphony, meant as requiem, becomes a national anthem for peace, forever linking her name to both suffering and healing.

The Long March Home

Genre: Epic Fantasy

Plot Idea: A warrior queen survives a devastating arrow wound that leaves her unable to ride or fight. As her realm faces rebellion, she must lead from her sickbed through diplomacy, intelligence, and moral authority.

Character Angle: Used to command through fear, she now learns to wield compassion and trust.

Twist(s): The arrowhead was cursed. It slowly turns to iron within her body. When the curse reaches her heart, she uses its final pulse to forge a binding treaty.

Long-term injuries test endurance in every sense: physical, mental, and emotional. When written with nuance, they become more than a limitation; they are a living part of who your character is.

By showing chronic pain, fatigue, and adaptation honestly, you remind readers that healing isn’t about returning to who we were, it’s about learning to live fully in who we’ve become.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

The Writer’s Guide to Psychological Trauma from Injuries

Posted on December 19, 2025 Leave a Comment

The broken bone, the blood, and the fever often take center stage when a character suffers a physical injury in a story. But many survivors of serious injuries will tell you that the psychological aftermath lasts far longer than the physical wounds.

For writers, portraying the emotional impacts, PTSD, and character reactions realistically not only adds depth but also honors the actual experiences of people who live with trauma. It turns injuries from onetime plot devices into ongoing character arcs.

What Is Psychological Trauma?

Psychological trauma is the emotional and mental response to an overwhelming event that threatens life, safety, or well-being. Injuries, especially violent or life-threatening ones, can trigger trauma responses long after the body heals.

Common forms in fiction include:

Acute Stress Reaction: Immediate panic, shock, or disassociation right after the injury.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Long-term condition with flashbacks, nightmares, and hypervigilance.

Depression and Anxiety: Fear, guilt, or despair tied to loss of mobility, disfigurement, or sense of identity.

Emotional Affects of Injuries

Fear and Hypervigilance

Characters may avoid situations that remind them of their injury (a knight refusing to wear armor again, a driver terrified of cars after a crash).

Anger and Frustration

At themselves (“Why wasn’t I stronger?”) or others (“They left me behind”).

Frustration with long recovery periods or physical limitations.

Guilt and Survivor’s Guilt

Feeling unworthy for surviving when others did not.

Blaming themselves for the circumstances that caused the injury.

Shame and Identity Loss

Disfigurement or disability can create shame in societies that prize strength or beauty.

A soldier unable to fight, a dancer unable to perform, or a mage who loses their magic gestures may feel stripped of identity.

Numbness and Avoidance

Detachment from others, withdrawal from relationships, or using humor to mask deeper pain.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

PTSD can develop after violent injuries, near-death experiences, or medical trauma. Realistic symptoms include:

Intrusive Memories: Flashbacks, nightmares, or uncontrollable thoughts about the injury.