The Writer’s Guide to Basic Anatomy

Understanding basic anatomy doesn’t just make your injury scenes more believable—it makes them more engaging. While you don’t need the expertise of a doctor, by focusing on how injuries affect the body, you can craft realistic, impactful moments that resonate with readers and deepen their connection to your characters. Take the time to research and incorporate anatomical accuracy, and you’ll create stories that feel grounded, visceral, and authentic.

Anatomy and Terminology

Here’s a guide to the essential anatomy and terminology every writer should know when portraying common injuries.

The Basics of the Human Body

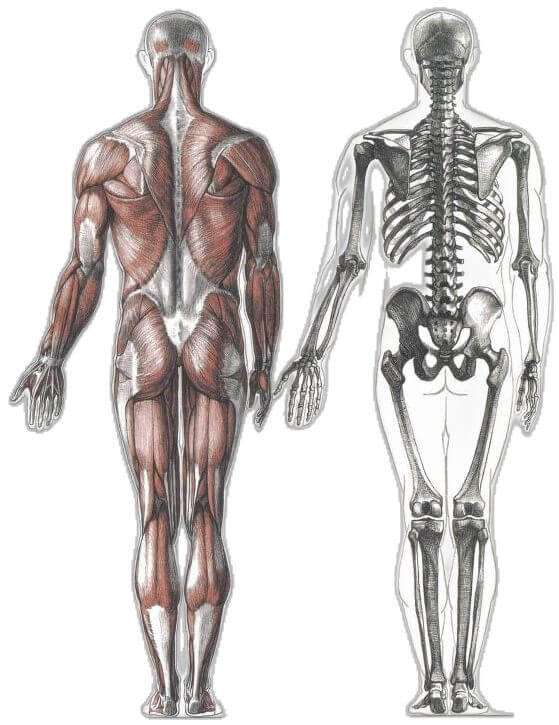

The human body is an intricate system of interconnected parts. To simplify, it’s helpful to divide it into three key layers – skin, muscles, and bones, with organs protected beneath.

Skin – The outer layer that protects the body from external harm. It’s highly vascularized, meaning even shallow cuts can bleed profusely.

Muscles – Tissues beneath the skin responsible for movement. Injuries to muscles can range from bruising (contusions) to tears (strains).

Bones – The rigid structure forming the skeleton. Breaks (fractures) can vary from hairline cracks to complete breaks, often requiring immobilization or surgery.

Organs – Vital structures like the heart, lungs, liver, and kidneys. Injuries to organs are usually life-threatening and require immediate medical attention.

Bones – The Framework of the Body

The skeleton gives the body its shape and supports movement. Key areas to understand when writing injuries include:

Skull – Protects the brain. A blow to the head can cause concussions, fractures, or traumatic brain injuries (TBI).

Spine (Vertebrae) – Composed of cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal vertebrae. Damage to the spine can cause paralysis or chronic pain.

Ribs – Protect the heart and lungs. Fractured ribs can puncture organs, causing internal injuries like pneumothorax (collapsed lung).

Pelvis – Supports the lower body and houses organs. Pelvic fractures are serious because of proximity to major arteries and nerves.

Limbs (Arms and Legs) – Long bones like the femur (thigh bone) and humerus (upper arm bone) are critical for mobility and prone to fractures during impacts.

Common injuries to bones include:

Fractures – Include simple (closed) fractures, where the bone doesn’t pierce the skin, and compound (open) fractures, where it does.

Stress Fractures – Tiny cracks in bones caused by repetitive stress, common in athletes or soldiers.

Dislocations – Forces can dislocate joints (like shoulders or hips), causing intense pain and requiring realignment.

Muscles and Tendons – Movers of the Body

Tendons attach muscles to bones and transmit the force needed for movement. Knowing the difference between muscles, tendons, and ligaments (which connect bones to other bones) can help you write detailed injury scenes.

Upper Body – Includes the biceps, triceps, deltoids (shoulders), and pectorals (chest). These are often involved in injuries from combat or heavy lifting.

Core – Abdominal muscles and the lower back stabilize the body. Strains here are common from overexertion.

Lower Body – Quadriceps, hamstrings, and calves drive movement. Pulled muscles or tears often happen during running or sudden exertion.

Common muscle and tendon injuries include:

Strains – Overstretching or tearing of muscle fibers. Severity ranges from mild (soreness) to severe (complete tears).

Tendinitis – Inflammation of a tendon, often from overuse. Common in joints like elbows and knees.

Ruptures – Tendons can snap completely, often requiring surgery.

Joints and Ligaments – Where Bones Meet

Joints are the pivot points of the body, allowing movement. They’re held together by ligaments, which are prone to injuries during twisting or impacts. Key joints include:

Shoulders – The most flexible joint, but also the most prone to dislocations.

Elbows – A hinge joint prone to sprains and fractures from falls.

Wrists and Ankles – Common sites for sprains, fractures, and repetitive stress injuries.

Knees – Complex joints stabilized by ligaments like the ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) and PCL (posterior cruciate ligament). Injuries here are common in sports.

Common joint injuries include:

Sprains – Overstretching or tearing of ligaments, often caused by twisting or impact.

Dislocations – Dislocations occur when something forces the bones in a joint out of position, resulting in intense pain and a visible deformity.

Cartilage Damage – Cartilage cushions joints; damage can lead to chronic pain or arthritis.

Vital Organs – Protecting Life

Organ injuries are among the most serious because they often involve internal bleeding or life-threatening complications. Understanding where organs are located can help you write injuries with precision. Key organs and their vulnerabilities include:

Brain – Enclosed in the skull, it’s susceptible to concussions or swelling from trauma.

Heart and Lungs – Protected by the ribcage. Injuries can include punctures (e.g., from broken ribs) or cardiac arrest from blunt trauma.

Liver and Spleen – Found in the abdominal cavity. The high vascularity of the liver and spleen makes injuries in this area prone to significant internal bleeding.

Stomach and Intestines – Susceptible to punctures from weapons or accidents. Injuries can cause infection or sepsis if not treated promptly.

Kidneys – Located in the lower back. Blows to the area can cause blood in the urine (hematuria) and long-term damage.

When describing internal entries, have your characters look for signs like sharp pain, swelling, blood loss (external or internal), or systemic symptoms like dizziness, nausea, or loss of consciousness. Internal injuries often require immediate intervention, especially if organs are bleeding.

Nervous System – The Body’s Communication Network

The nervous system, comprising the brain, spinal cord, and nerves, controls all bodily functions. Damage to the nervous system can have long-term or permanent consequences. Common nerve injuries include:

Concussions – A type of traumatic brain injury caused by blows to the head. Symptoms include headaches, dizziness, memory loss, and confusion.

Spinal Cord Injuries – These can lead to paralysis (paraplegia or quadriplegia) depending on the level and severity of the damage.

Nerve Compression or Damage – Conditions like sciatica (pain radiating down the leg) or carpal tunnel syndrome (wrist pain from repetitive strain) can impair movement and cause chronic pain.

Blood and Circulatory System

Blood plays a vital role in injury descriptions, whether it’s external bleeding or internal hemorrhage. Understanding types of blood vessels helps with realistic depictions.

Arteries – Carry oxygenated blood from the heart. Arterial wounds bleed in spurts and are life-threatening.

Veins – Carry deoxygenated blood back to the heart. Venous bleeding is steady but less forceful.

Capillaries – Tiny vessels near the skin’s surface. Capillary bleeding is slow and often seen in abrasions or shallow cuts.

When writing injuries, think about:

Location – Where is the injury located? How does it affect movement or function?

Severity – Is it a minor injury (bruise, shallow cut) or severe (fracture, organ damage)?

Realistic Symptoms – Include pain, swelling, limited motion, or systemic symptoms like fever (from infection) or shock (from blood loss).

Consequences – How does the injury impact the character physically and emotionally? Does it slow them down, alter their plans, or create new conflicts?

Writing Non-Human Injuries

In fantasy and science fiction, characters often belong to unique races or species with anatomy and physiology that differ from humans. Understanding how to create and describe these differences can deepen your world-building and bring more authenticity to your story. When these non-human characters sustain injuries, their unique biology offers opportunities to explore creative healing processes, vulnerabilities, and strengths. Here’s how to approach the anatomy and physiology of non-human characters and how it can enhance your depiction of injuries.

Understanding the Purpose of Non-Human Anatomy

When designing a non-human species, consider their environment, lifestyle, and culture. Environment, lifestyle, and culture influence their anatomy and determine how they sustain or heal from injuries. Is the species aquatic, terrestrial, aerial, or a combination? You must consider anatomical features, such as fins, wings, or gills. Does the species have natural armor, regeneration abilities, or unique sensory organs? These could impact how injuries affect them. Are injuries seen as shameful, honorable, or irrelevant? This will influence how they react to injuries and seek treatment.

Key Elements to Define in Non-Human Anatomy

To effectively describe injuries for non-human characters, focus on:

Skin or External Covering – Scales, fur, feathers, exoskeletons, or skin-like membranes. Scaled species might suffer cracked or missing scales, leaving sensitive areas exposed. Characters with an exoskeleton could face problems like chitin fractures, which might require molting to heal fully. If feathers are singed, plucked, or damaged, it can affect a flying character’s ability to travel.

Bones and Structural Support – Bones, cartilage, or exoskeletons. Some species might have no internal skeleton, like jellyfish-inspired creatures. A species with hollow bones (like bird-like creatures) might be more prone to fractures but heal faster because of lighter weight. Exoskeletons could be resilient to minor impacts but vulnerable to crushing forces or penetration.

Musculature – Flexible, dense, or specialized for unique abilities like flying or enhanced strength. Winged characters might suffer ligament tears or muscle damage, grounding them until healed. A species with prehensile tails might strain or break tail muscles, impairing balance or combat ability.

Organs – Multiple hearts, redundant lungs, or specialized organs for magic or energy production. Redundant organs (e.g., two hearts) might make the species more resilient to certain injuries. Unique organs (e.g., an energy core) could create dramatic injury consequences if damaged, such as magic disruptions or power loss.

Nervous System – Centralized like humans or distributed like octopuses.A distributed nervous system could make it harder to “kill” the character, but injuries to specific areas might cause partial paralysis or movement issues.Non-human sensory organs, such as antennae or echolocation, may impair the character if damaged.

Circulatory System – Single heart, multiple hearts, or an entirely unique system like hemolymph (as in insects).Hemolymph leaks in a creature with an open circulatory system might be less dramatic than arterial bleeding, but could still be fatal.Blood color (e.g., green or blue) could visually differentiate injuries.

Regeneration Abilities – Partial (like lizards regrowing tails) or complete (like sci-fi species with rapid healing). Regeneration might not work on vital organs, or it might drain the character’s energy, requiring rest or food to recover fully. Injuries might heal in strange or imperfect ways, such as mismatched scales or malformed limbs.

Describing Injuries in Non-Human Characters

When injuries occur, take advantage of the unique anatomy you’ve created to craft compelling, vivid descriptions. Here are a few ideas based on different aspects of non-human physiology:

Unique Wound Appearance – A character with a metallic exoskeleton might have dents or cracks instead of cuts. A creature with translucent skin could display internal bleeding visibly.

Exotic Fluids – Blood or equivalent fluids might differ in color, consistency, or even smell. For example, a character’s injuries could ooze glowing green plasma rather than red blood.

Unusual Pain Responses – Some species might not feel pain as humans do, experiencing sensations like heat, pressure, or an electrical pulse instead.

Regeneration and Healing – Highlight the visible stages of regrowth or recovery. For example, a lizard-like species might regenerate a tail slowly, starting with a small nub that grows larger over weeks.

Unique Consequences – Damage to magical or energy-based organs might cause loss of powers, difficulty maintaining their natural form, or the inability to control their environment.

Treating Injuries in Non-Human Characters

The culture, technology, and biology of your world reflect how injuries are treated.

Magical Healing in Fantasy – Magical creatures may respond differently to healing spells, potions, or rituals. Healing might restore the physical body but cannot regenerate magical energy or soul-related damage. Magical healing could have side effects, like leaving scars that glow, drawing life force from others, or permanently altering the character’s abilities.

Advanced Technology in Science Fiction – Nanotechnology might repair wounds at a cellular level, but damage to advanced alien physiology might require custom medical solutions. Alien characters might have biotechnology integrated into their bodies, requiring repairs that combine organic and mechanical processes. If the species is cybernetic, repairs might involve software updates or mechanical replacements rather than traditional healing.

Traditional Remedies – Non-human societies might use unique herbs, salves, or even symbiotic organisms to heal wounds. For example, a character could apply a medicinal slime or allow small creatures to clean and close their wounds. Cultural beliefs could influence treatment—perhaps some species see scars as honorable and avoid “perfect” healing methods.

Enhancing Storytelling Through Non-Human Injuries

By leaning into the unique traits of your fantasy or sci-fi races, injuries become more than obstacles; they become storytelling opportunities.

Highlight Vulnerabilities – An impervious species might have one critical weakness that raises the stakes.

Create Cultural Significance – Scars, missing limbs, or other injury signs might symbolize honor, shame, or coming of age.

Develop New Plot Points – A character might seek rare healing herbs, advanced technology, or a magical ritual to recover, creating new story arcs.

Realistically Portraying Injuries Without Slowing the Story

Realistically depicting injuries can add depth and tension to your narrative, but it’s easy to get bogged down in excessive details or disrupt the pacing. Striking the right balance between authenticity and storytelling ensures your readers stay engaged while still believing in the consequences of your character’s injuries. Here are some practical tips to achieve that balance.

Focus on the Impact, Not the Medical Details

While accuracy is important, your readers don’t need a detailed medical report. Instead, focus on how the injury affects the character’s actions, decisions, and relationships. For example, instead of explaining every step of treating a broken leg, highlight how the character struggles with mobility or feels vulnerable in a dangerous situation.

Show how the injury limits the character’s abilities or adds tension to their journey. Describe physical sensations (pain, stiffness, fatigue) or how it complicates interactions with others. Avoid long medical jargon or unnecessary descriptions of procedures unless they’re critical to the plot or character development.

Instead of: “The medic adjusted the tibial fracture, splinted the leg, and applied antiseptic before wrapping the wound.”

Try: “Every step sent a jolt of pain through her leg, forcing her to lean heavily on her companion. She hated feeling like dead weight, but the alternative was collapsing in the dirt.”

Use Injury as a Tool for Tension and Growth

Injuries are more than physical setbacks—they’re opportunities to reveal vulnerabilities, build relationships, and push your characters to adapt. Use injuries to show how a character copes under pressure, leans on others, or grows.

Let the injury affect the character’s decisions and create new challenges. Use the downtime for introspection, emotional development, or important conversations. Don’t treat injuries as a minor inconvenience or remove their impact too quickly. The consequences of injuries should last long enough to feel meaningful.

Example: “He winced as he tightened the makeshift bandage around his arm. Every movement made the gash throb, but there was no time to stop. If he didn’t keep moving, they’d find him—bleeding or not.”

Highlight the Character’s Experience Over the Mechanics

Readers care more about what your character is feeling than the technical details of their injury. Focus on sensory descriptions (pain, fatigue, frustration) and emotional reactions to make the injury resonate.

Use the character’s perspective to describe the injury. How does the pain affect their thoughts? Do they feel fear, anger, or determination? How does the injury challenge their personality or values? Avoid clinical, detached descriptions that feel more like a textbook than storytelling.

Instead of: “The arrow pierced through his shoulder, hitting the rotator cuff and causing a deep, clean wound.”

Try: “A searing pain shot through his shoulder as the arrow struck, his arm falling limp at his side. He bit down hard to keep from screaming, each breath sharper than the last.”

Show Realistic, Progressive Recovery

Recovery from injuries doesn’t happen overnight, but you can still portray it without slowing the story. Show the recovery in stages, using brief moments to illustrate improvement or setbacks rather than dragging out the process.

Use time skips, montages, or concise scenes to show progress. Highlight milestones like regaining mobility or overcoming pain. Avoid making recovery feel instant or, conversely, spending multiple chapters on repetitive descriptions of healing.

Example: “Weeks later, she still limped when she walked, but the sharp pain had dulled to an ache. She gritted her teeth and pressed on—the wound had taken enough of her time already.”

Use Injuries to Deepen Conflict

An injury can create both internal and external conflict. Internally, the character might struggle with frustration, vulnerability, or self-doubt. Externally, it might force them to rely on others, delay their plans, or leave them exposed to enemies.

Let the injury add stakes to the story. Maybe the injury prevents the character from fighting back during a key confrontation, or their recovery slows the group’s progress, creating tension with allies. Avoid resolving injuries without meaningful consequences. Let the injury serve a purpose in the plot or character arc.

Example: “His shoulder throbbed with every swing of the sword, but stopping wasn’t an option. He had to push through—if he failed now, the injury wouldn’t matter. They’d all be dead.”

Keep the Pacing in Mind

Injury scenes should enhance the story, not halt it. Focus on the most critical details and move quickly to what happens next. Injuries are tools to heighten tension and drama, but they shouldn’t overshadow the main plot.

Incorporate injuries into the flow of the story. Use concise, impactful descriptions that show the stakes and consequences without lingering too long. Avoid overly detailed, drawn-out scenes unless the injury itself is the focal point of the chapter.

Instead of: “She fell to the ground, her leg at an awkward angle. She screamed as she clutched her knee, the pain shooting up her thigh like fire. She tried to move, but every attempt sent waves of agony through her body.”

Try: “She hit the ground hard, her knee twisting painfully beneath her. She bit back a scream, the fiery pain making it clear—she wasn’t getting back up anytime soon.”

Integrate Injuries into the Plot Seamlessly

Rather than treating injuries as separate events, weave them into the story’s natural progression. Show how the character’s physical limitations shape their goals, relationships, and decisions without derailing the main plot.

Use the injury as a subplot that intersects with the main story. Maybe the character’s injury delays their ability to rescue someone, forcing them to rely on others or find alternative solutions. Avoid letting the injury feel isolated from the larger narrative.

Example: “The gash on her side burned with every step, but she forced herself to keep moving. If she didn’t make it to the village by nightfall, she’d have bigger problems than an infected wound.”

Let the Character’s Personality Shine Through

Injuries are opportunities to reveal character traits. How a character reacts to pain, frustration, or helplessness can say a lot about who they are. A stoic warrior might grit their teeth and press on, while an impatient character might lash out at their allies.

Show how the injury affects the character emotionally and mentally. Use it to deepen their personality and relationships. Avoid making all characters react to injuries in the same way. Tailor the response to fit their personality and circumstances.

Example: “She hated asking for help, but as she tried and failed to lift her arm, she swallowed her pride and called for her friend. ‘Don’t say a word,’ she muttered as they helped her up.”

Understanding basic anatomy doesn’t just make your injury scenes more believable—it makes them more engaging. By focusing on how injuries affect the body, you can craft realistic, impactful moments that resonate with readers and deepen their connection to your characters. Take the time to research or world-build, incorporate anatomical accuracy, and you’ll create stories that feel grounded, visceral, and authentic.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.