The Writer’s Guide to Broken Bones

Breaking a bone is one of the most common and impactful injuries in fiction. Whether it happens during a dramatic fight scene, a tragic accident, or an adventurous misstep, fractures offer an opportunity to showcase your character’s resilience, vulnerability, and recovery journey. To write these scenes realistically, it’s essential to understand the types of fractures, their symptoms, and the healing process.

Types of Bone Fractures

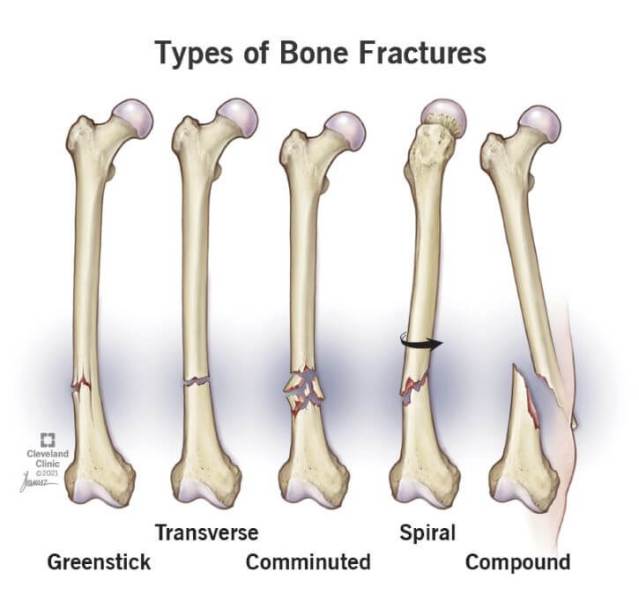

Not all broken bones are the same. Understanding the type of fracture can help you determine the severity of the injury and how it will affect your character.

Simple (Closed) Fracture

Definition: The bone breaks but does not pierce the skin.

Symptoms: Swelling, bruising, pain, and an inability to move the affected area.

Impact on Story: These fractures are less dramatic but still debilitating. They often require immobilization (e.g., a cast) and weeks to months of healing.

Compound (Open) Fracture

Definition: The bone breaks and pierces through the skin.

Symptoms: Severe pain, bleeding, visible bone, and risk of infection.

Impact on Story: Compound fractures are graphic and life-threatening. They introduce complications like blood loss, shock, and infection, adding tension and urgency to the narrative.

Hairline (Stress) Fracture

Definition: A thin crack in the bone, often caused by repetitive stress or overuse.

Symptoms: Mild pain that worsens with activity, swelling, and tenderness.

Impact on Story: These fractures are less dramatic but can force characters to slow down or rethink their actions.

Greenstick Fracture

Definition: Common in children, this is a partial fracture where the bone bends and cracks but doesn’t break completely.

Symptoms: Pain, swelling, and difficulty using the limb.

Impact on Story: This type of fracture might be more suitable for younger characters or those with unique physiology (e.g., in fantasy species).

Comminuted Fracture

Definition: The bone shatters into multiple pieces, often from high-impact trauma.

Symptoms: Severe pain, deformity, swelling, and immobility.

Impact on Story: This type of fracture is severe and may require surgery. It’s ideal for high-stakes moments like battle scenes or catastrophic accidents.

Spiral Fracture

Definition: A twisting motion causes the bone to fracture in a spiral pattern.

Symptoms: Pain, swelling, and visible deformity.

Impact on Story: These fractures might occur during combat or athletic activities, adding a layer of realism to dynamic action scenes.

Symptoms of a Broken Bone

When writing a scene where a character breaks a bone, it’s important to convey their immediate symptoms and reactions. These symptoms will vary based on the severity of the fracture.

Pain: Intense and localized, often worsening with movement or pressure.

Swelling and Bruising: The area around the break may become swollen, discolored, and tender.

Deformity: The affected limb or joint might appear misshapen or out of place.

Immobility: Characters may find it difficult or impossible to move the injured part.

Audible Sounds: In some cases, the character (or those around them) might hear a crack or snap when the bone breaks.

Shock: Severe fractures, especially compound ones, can cause symptoms of shock, such as pale skin, rapid breathing, and confusion.

The Healing Process

Breaking a bone is just the beginning. The healing process provides opportunities for character development and introduces physical and emotional challenges.

Stage 1: Inflammation (0–7 Days)

What Happens: The body sends blood to the injury, forming a clot around the broken bone. Swelling, bruising, and pain are at their peak during this stage.

For Your Story: Show the character dealing with acute pain and limited mobility. They may need help with basic tasks, highlighting their vulnerability.

Stage 2: Bone Repair (1–6 Weeks)

What Happens: A soft callus forms around the break, eventually hardening into new bone. Swelling subsides, and the character may regain limited use of the limb.

For Your Story: Depict moments of frustration or minor victories as the character adjusts to their limitations. Perhaps they begin physical therapy or attempt to push themselves too hard, risking reinjury.

Stage 3: Bone Remodeling (6 Weeks–Months)

What Happens: The body reshapes and strengthens the new bone, but full recovery can take months or even years.

For Your Story: Show long-term effects, such as lingering pain, stiffness, or even permanent changes (e.g., a limp or reduced strength). These aftereffects can add depth and realism to your character.

Adding Depth to the Healing Journey

While the healing process can slow the pacing of your story, it’s also an opportunity for character growth. Here are ways to keep the narrative engaging during recovery:

Emotional Struggles

Characters may feel frustration, helplessness, or anger about their injury. For a warrior, the inability to fight could lead to feelings of worthlessness, while an adventurer might worry about letting down their companions.

Example: “He clenched his fists as he stared at the crutches propped against the wall. The fight was still raging outside, and here he was, useless and sidelined. The frustration burned hotter than the pain in his leg.”

Interpersonal Conflict

Recovery often forces characters to rely on others, which can lead to tension or deepen relationships. A fiercely independent character might struggle to accept help, or a caregiver might grow resentful of the extra burden.

Example: “She hated asking for help, but the splint on her arm left her no choice. ‘Can you tie this?’ she muttered, holding out the bandage. The look on his face made it clear he wouldn’t let her forget this.”

Setbacks and Triumphs

Introduce small victories and setbacks to keep the recovery process dynamic. A character might celebrate taking their first step unaided, only to fall and reinjure themselves.

Example: “The first step was agony, but she refused to stop. Her muscles screamed, her vision blurred with tears, but when she finally stood on her own, she couldn’t help but grin.”

Long-Term Consequences

Broken bones can leave lasting effects that shape your character beyond the initial injury. Consider including:

Scarring: A compound fracture might leave visible scars.

Mobility Issues: Severe fractures could cause a limp, reduced strength, or limited range of motion.

Psychological Impact: The memory of the injury might make the character cautious, fearful, or hesitant in future situations.

Chronic Pain: Some fractures, especially if poorly treated, can lead to lifelong pain or discomfort.

Example: “Even months later, his leg ached when the weather turned cold. It was a subtle reminder of the battle he barely survived—a reminder he didn’t need but couldn’t escape.”

Treatments for Broken Bones Across Time

How characters treat broken bones depends on the resources, knowledge, and cultural practices of their time. Advancements in science and technology have driven the evolution of broken bone treatment, from rudimentary splints in ancient history to futuristic bone regrowth technologies. Each era brings unique challenges and opportunities for storytelling, from the desperation of pre-modern remedies to the ethical quandaries of futuristic medicine. This section explores treatments for fractures in the ancient world, medieval world, modern contemporary medicine, and potential future innovations.

Ancient World Treatments

In ancient times, treatments for broken bones relied heavily on observation, intuition, and natural remedies. While often crude by today’s standards, some methods were surprisingly effective.

Splinting and Immobilization: Ancient civilizations like the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans recognized the importance of immobilizing broken bones. They used materials like wood, reeds, or cloth to create splints. The Edwin Smith Papyrus (circa 1600 BCE) from Egypt contains descriptions of fracture treatments, including setting bones and immobilizing them with bandages.

Traction Techniques: Ancient Indian and Chinese medical texts describe basic traction methods to realign bones. These often involved pulling the limb to straighten it before splinting.

Herbal Remedies: Herbs were applied to reduce swelling and pain. People used willow bark, a natural source of salicylic acid (a precursor to aspirin), for pain relief.

Challenges in Treatment: Without understanding of infection, compound fractures were particularly deadly. Infections from open wounds often resulted in amputation or death. Healing relied on rest and natural recovery, which could lead to improperly healed bones and long-term deformities.

In Your Writing: Depict the resourcefulness of ancient healers by emphasizing natural materials and creative problem-solving. Highlight the risks of infection and limited understanding of anatomy to add tension to injury recovery.

Example: “The healer laid out strips of softened bark and bound the boy’s arm tightly to a wooden splint. ‘Don’t move it,’ she warned. ‘The bone will only heal if it stays straight.’”

Medieval Treatments

Though a lack of understanding of germ theory and internal anatomy limited advances, the medieval period saw progress in bone treatment.

Setting Bones: Medieval healers (often monks or barbers) used manual techniques to realign bones. Healers sometimes employed traction to straighten fractures before immobilization. Wooden or leather splints were common. Bandages soaked in natural adhesives like egg whites or flour might secure splints.

Medicinal Poultices: Poultices made from herbs like comfrey (known as “knitbone”) were applied to promote healing. Honey and wine, known for their antibacterial properties, were sometimes used to clean wounds.

Amputation for Severe Cases: Compound fractures often led to infection, requiring amputation to prevent gangrene. Surgeons performed amputations without anesthesia, using basic tools like saws or knives.

Faith-Based Healing: Medicine and religion were often interwoven in the medieval world. Prayers, blessings, and holy relics were part of the healing process.

In Your Writing: Medieval treatments can add gritty realism to your story. Highlight the pain of setting bones without anesthesia or the desperation of using untested remedies. Show the interplay between faith and medicine to deepen the cultural context.

Example: “The blacksmith’s arm was bound tightly with strips of linen, a salve of comfrey and honey slathered over the break. He gritted his teeth as the barber-surgeon tugged the limb straight, muttering a prayer to St. Roch for mercy.”

Contemporary Medicine

Modern medicine provides advanced techniques for treating broken bones, drastically improving outcomes and reducing recovery times.

Diagnosis: X-rays or CT scans are used to confirm the type and severity of the fracture.

Immobilization: Plaster or fiberglass casts are used to immobilize bones and ensure proper alignment during healing. Doctors often use temporary immobilization devices for less severe fractures.

Surgical Intervention: Severe fractures may require surgical repair. Sometimes, metal hardware is used to stabilize the bone. Devices outside the body hold the bone in place for complex fractures.

Pain Management: Doctors prescribe medications such as acetaminophen or prescription opioids to manage pain.

Physical Therapy: Once the bone heals, patients undergo therapy to rebuild strength, mobility, and function.

In Your Writing: Modern treatments can convey the efficiency and precision of contemporary medicine. Highlight the detailed diagnostic process, the relief of effective pain management, or the frustration of physical therapy to add realism.

Example: “The X-ray showed a clean break along the radius. The doctor explained the surgery: a small titanium plate to hold the bone together, followed by six weeks in a cast. Relief flooded through her—at least it wasn’t permanent.”

Future Treatments

In speculative settings like science fiction, the possibilities for treating broken bones expand dramatically. Advances in biotechnology and materials science could revolutionize fracture care.

Bone-Repairing Nanobots: Microscopic robots could enter the bloodstream, repairing fractures at the cellular level by binding bone tissue or even rebuilding it from scratch.

3D-Printed Implants: Surgeons could print custom bone grafts or implants on-demand, designed to fit perfectly into the fracture site and stimulate rapid healing.

Stem Cell Therapy: Doctors might inject stem cells to accelerate bone regeneration and repair.

Synthetic Biologics: Artificial compounds could mimic natural bone growth, reducing healing times to days instead of months.

Exoskeletal Support: Advanced braces or exoskeletons could provide mobility while stabilizing fractures, allowing characters to remain active during recovery.

Instantaneous Healing Devices: In extreme futuristic settings, devices like “bone-knitting lasers” or sprays that harden fractures instantly could eliminate the need for prolonged recovery.

In Your Writing: Futuristic treatments offer exciting possibilities for creative storytelling. Highlight the ethical dilemmas, technological failures, or cultural differences surrounding these innovations. Consider the implications of instant recovery—does it remove the emotional weight of injury, or does it come at a cost?

Example: “The med-bot hovered over his shattered femur, deploying a swarm of nanobots. Within moments, the pain ebbed as the fracture knitted itself together. ‘You’ll be running again in 12 hours,’ the technician said. ‘Just don’t think about the price tag.’”

Plot and Character Ideas

Broken bones can serve as more than just physical injuries; they can act as catalysts for character development, interpersonal conflict, and plot twists. Below are plot and character ideas that center on fractures, including examples for science fiction and fantasy settings with characters of varied physiologies.

The Unhealing Break

Plot Idea: A character suffers a bone fracture that refuses to heal because of a magical curse, alien infection, or technological malfunction. The injury worsens over time, causing pain and limiting their abilities, forcing them to search for a cure while under constant physical duress.

Character Angle: A proud warrior struggles with the shame of being unable to fight while also confronting their mortality.

Fantasy Twist: A cursed weapon inflicted the fracture, and the bones grow jagged or warp over time unless the curse is lifted.

Science Fiction Twist: The character has synthetic bone implants that are malfunctioning, and their body is rejecting the augmentation.

The Bone Collector

Plot Idea: A healer or scientist seeks rare materials to repair or regrow shattered bones. These materials come from dangerous creatures or forbidden locations, setting the stage for an adventurous quest.

Character Angle: A scholar or medic, usually non-combative, must take up arms or rely on a team to gather what’s needed. Their quest reveals a hidden resilience or bravery.

Fantasy Twist: The bone materials come from mythical beasts like dragons or giants, requiring the character to outwit or slay the creatures.

Science Fiction Twist: The materials are rare alien minerals or nanobot technologies found only on a hostile planet or deep in space.

A Fragile Hero

Plot Idea: A hero with a condition that causes fragile bones (e.g., osteogenesis imperfecta or brittle bones syndrome) faces incredible odds. Despite their physical limitations, they use ingenuity, strategy, and determination to overcome challenges.

Character Angle: The character’s struggle with their condition gives their arc emotional weight and depth, showing that heroism isn’t defined by physical strength alone.

Fantasy Twist: A spell or magical artifact keeps their fragile bones intact, but it comes with a cost—such as draining their life force or emotional energy.

Science Fiction Twist: They fight using powered exoskeletons or synthetic enhancements, but the failure of these aids leaves them dangerously exposed.

The Price of Healing

Plot Idea: After breaking a bone at a pivotal moment, someone offers the character a miraculous but morally questionable healing method. The decision to accept it has profound consequences for themselves and others.

Character Angle: The character must weigh their personal survival against ethical dilemmas, such as exploiting a sentient creature or stealing resources from those in greater need.

Fantasy Twist: The healing requires the life force or bones of another creature, creating a moral conflict about sacrifice and necessity.

Science Fiction Twist: The character must implant alien DNA or rely on experimental nanotechnology that alters their physiology, potentially making them less human.

A Fracture in Time

Plot Idea: A character breaks a bone while exploring a magical or technological anomaly, such as a time rift or a cursed artifact. The fracture becomes a clue to unraveling the mystery—perhaps it heals unnaturally fast, grows abnormally, or carries an imprint of the anomaly’s energy.

Character Angle: The injury forces the character to reconsider their role in the unfolding events, transitioning from a passive observer to an active participant.

Fantasy Twist: The fracture glows faintly and causes visions of the past or future, making it both a burden and a source of insight.

Science Fiction Twist: The bone regenerates alien tissue or absorbs technological data, creating opportunities—and dangers—for the character.

The Broken Leader

Plot Idea: A leader breaks a bone at a critical moment, leaving them unable to physically guide their group. They must lead through wisdom and strategy rather than action, relying on others to execute their plans.

Character Angle: The injury forces the leader to face insecurities about their worth beyond physical prowess and strengthens their bond with their team.

Fantasy Twist: The leader’s broken bone is a sign of a prophecy, interpreted as either a good or bad omen by their followers.

Science Fiction Twist: The fracture disables the neural implants they rely on to communicate or control their crew, leaving them vulnerable.

Alien or Mythical Physiology Challenges

Plot Idea: A character with a non-human physiology suffers a unique fracture that requires entirely unconventional treatment. The injury could have cascading effects on their biology, affecting their behavior, abilities, or survival.

Character Angle: The character’s injury challenges others to understand and accept their differences, fostering empathy or conflict within the group.

Fantasy Twist: A centaur breaks a leg, which is both life-threatening and emotionally devastating, as it renders them unable to run—a core part of their identity.

Science Fiction Twist: A crystalline alien species cracks a vital “bone,” threatened their structural integrity. Their teammates struggle to repair them using unfamiliar technology.

The Healing Trial

Plot Idea: To recover from a broken bone, the character must undergo a grueling trial or test. The process is physical, emotional, or even spiritual, forcing them to confront their fears, limits, or inner demons.

Character Angle: The injury becomes symbolic of the character’s internal struggles, and their healing journey mirrors their growth.

Fantasy Twist: The trial involves seeking a legendary healer or magical spring, but only the worthy can access its power.

Science Fiction Twist: The character must trust an advanced AI or alien entity to guide their recovery, grappling with the fear of losing their autonomy.

The Warrior’s Scar

Plot Idea: A character’s broken bone heals poorly, leaving them with a permanent scar or limp that affects their fighting ability. They must adapt to their new limitations and find new ways to be effective.

Character Angle: The character struggles with feelings of inadequacy, eventually discovering strength in their adaptability and experience.

Fantasy Twist: A magical artifact offers to restore their strength, but it comes with a heavy price, such as binding them to an ancient spirit.

Science Fiction Twist: They change their body with biomechanical implants, but the enhancements come with unexpected side effects, like emotional detachment or societal rejection.

The Stolen Bone

Plot Idea: In a world where bones hold magical or technological power, thieves steal or harvest a character’s broken bone for nefarious purposes. The character must retrieve it or deal with the loss.

Character Angle: The character wrestles with anger, betrayal, or loss of identity tied to their stolen bone, while proving they can overcome adversity without it.

Fantasy Twist: A villain uses the stolen bone to cast a powerful curse or summon a creature, and the character feels a lingering connection to the magic.

Science Fiction Twist: The stolen bone contains vital genetic or technological information, making the character a target for factions that want to control or destroy it.

Writing about broken bones offers a wealth of storytelling opportunities, from dramatic injury scenes to rich character arcs during recovery. By understanding the types of fractures, symptoms, and healing processes, you can create compelling, realistic portrayals that keep readers engaged. Remember, it’s not just about the injury—it’s about how it challenges and changes your characters, both physically and emotionally. With careful attention to detail and a focus on the human (or non-human) experience, you can make even the smallest fracture a pivotal moment in your story.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.