The Writer’s Guide to Stab Wounds

Stab wounds can be quick and deadly, slow and painful, or messy and traumatic depending on location, depth, weapon type, and the world your story inhabits. However, a well-written stabbing scene isn’t just about blood – realistic portrayal involves anatomy, physics, psychology, and consequences.

This guide will help you realistically depict stab wounds, explaining how injury severity, weapon characteristics, survival odds, and long-term effects should shape the narrative. I’ll also cover the important distinction between a puncture wound and a stab wound.

What’s the Difference Between a Puncture and a Stab?

Puncture Wound

A puncture wound is caused by a narrow, pointed object penetrating the skin (e.g., needles, nails, spikes). Minimal external bleeding, but high risk of deep internal damage or infection because the wound seals over quickly. Often small in surface area but deep, with a higher chance of invisible internal injuries.

Stab Wound

A stab wound is a deeper-than-wide injury caused by a bladed weapon, like a knife, dagger, or sword. Significant external and internal damage, depending on blade size and force. Typically, longer entry wounds than punctures, and often involve cutting and penetrating.

Quick Tip: A knife thrust into the belly? Stab wound.Stepping on a rusty nail? Puncture wound.

Key Factors That Determine Stab Wound Severity

Location on the Body

Where the character is stabbed dramatically influences their survival odds and consequences.

Chest: May puncture lungs, heart, or major arteries. Low odds if heart/lung is hit without immediate aid.

Abdomen: Risk of damage to intestines, liver, kidneys. Moderate odds; depends on internal bleeding or infection.

Neck: Risk to jugular veins, carotid artery, windpipe. Very low survival without immediate help.

Back: Can damage lungs, kidneys, spine. Moderate to low odds depending on area hit.

Arm/Leg: May hit muscles, arteries (like brachial or femoral). High odds, unless a major artery is cut.

Shoulder: Often survivable but can involve nerve damage. High odds with proper care.

Depth of the Wound

Shallow stabs (skin and fatty tissue): Painful but survivable with basic treatment.

Medium depth (muscle layer): More serious, impairing movement and strength; risks bleeding and infection.

Deep stabs (organs, arteries, bones): Life-threatening. Risk of shock, massive internal bleeding, or organ failure.

Penetrating stabs (full thrusts): Especially dangerous if the weapon passes through to vital organs or major vessels.

Quick Tip: A deep abdominal stab can lead to sepsis if the character survives the initial injury.

Type of Weapon

Straight Blades (e.g., dagger, stiletto, sword point): Designed for deep, clean thrusts. May cause narrow but deadly wounds, ideal for reaching vital organs quickly.

Serrated Blades (e.g., survival knives, combat knives): Tear tissue when entering or being pulled out. Harder to close surgically, leading to longer healing times and worse scars. Extraction often causes more damage than the stab itself.

Small Blades (e.g., kitchen knives, daggers): Penetration depends on force applied and target’s clothing/armor. Less likely to reach deep organs without significant force.

Large Blades (e.g., swords, bayonets, long knives): Greater range and potential for massive trauma, often causing gaping wounds rather than clean holes.

Quick Tip: A rapier thrust might cause a deep, fatal organ puncture. A serrated combat knife slash might cause a horrific, bleeding flesh wound with lasting nerve damage.

Immediate Effects of a Stab Wound

Sharp, immediate pain at the site of injury.

Bleeding, profuse if arteries or veins are hit.

Shock, the body’s response to trauma, can set in within minutes.

Difficulty breathing (if lungs are involved).

Paralysis or weakness (if spinal cord or major nerves are damaged).

Internal bleeding which may not be immediately visible.

Collapse, especially with chest, neck, or major abdominal wounds.

Quick Tip: Pain isn’t always instant. Shock and adrenaline can delay the pain for several minutes.

Survival Odds and Long-Term Effects

Survival Odds

High for limb wounds (unless major arteries are severed).

Moderate for abdominal wounds if medical treatment is rapid.

Low for chest or neck wounds involving vital organs.

Long-Term Effects

Chronic Pain: Nerve damage may cause lifelong issues.

Reduced Mobility: Shoulder, knee, or abdominal stabs may limit physical abilities.

Infection: Pre-modern settings or dirty environments increase risk dramatically.

Scarring: Deep stab wounds almost always leave scars.

Psychological Trauma: Fear of crowds, knives, or touch may follow.

Plot Implications for Stab Wounds

Survival doesn’t mean unscathed.

Mobility may be limited—especially after chest, abdomen, or joint stabs.

Recovery can take weeks to months, even with modern medical care.

Risk of internal bleeding or infection can keep tension high even after the initial injury.

Emotional impact (e.g., PTSD, vengeance, guilt) can shape character arcs.

Quick Realism Tips for Writing Stab Wounds

Force matters: A shallow, half-hearted thrust won’t kill a healthy adult unless it hits a major artery or organ.

Withdrawal of the blade can cause more bleeding—especially with serrated edges.

Shock is silent: A character may slump, confused or pale, without screaming.

In real-world fatal attacks, multiple stab wounds are often necessary – not the single, perfect Hollywood kill.

Vital areas are small: Hitting the heart or aorta requires precision and luck.

Armor or thick clothing matters: Leather armor, chain-mail, or heavy coats can significantly reduce penetration.

Depicting Stab Wounds Across Genres

Stab wounds can feel very different depending on the genre you’re writing in. Whether it’s a modern mugging, a medieval duel, a magical battle, or a space-age assassination, the way you describe a stab wound and the consequences that follow should reflect your story’s setting, technology, and tone.

In this guide, I’ll break down how writers portray stab wounds differently across contemporary, historical, fantasy, and science fiction genres, and how time period and cultural inspirations influence the type of blades used.

Contemporary

In modern fiction, readers expect a realistic, medically accurate portrayal. Stab wounds are ugly, chaotic injuries, not clean surgical strikes.

Weapons Used

Common weapons include kitchen knives, hunting knives, folding knives, and sometimes improvised weapons (screwdrivers, scissors). Blades are shorter and easier to conceal.

Fight Dynamics

Stabbings are usually fast, messy, and fueled by fear, adrenaline, or rage. Characters may be stabbed multiple times. Single-stab kills are rare unless the heart, neck, or brain is struck precisely.

Medical Consequences

Survival depends on the location, depth, and speed of medical intervention. Psychological trauma (PTSD, hypervigilance) often follows surviving an assault. Even “minor” wounds can become deadly because of organ damage or infection.

Example: A mugging victim stabbed in the abdomen might collapse from internal bleeding minutes later, not instantly—and even if they survive, they might never feel completely safe again.

Historical

The type of blade and the nature of stab wounds depend heavily on the era, region, and social class depicted.

Blades by Era and Culture

Ancient (Greece, Rome) – Short swords like the gladius, xiphos – Designed for thrusting into vital areas during tight combat.

Medieval Europe – Daggers, arming swords, longswords – Daggers used in close quarters, swords often for slashing and thrusting.

Renaissance- Rapiers, main gauche (parrying dagger) – Emphasis on dueling, precision stabbing, targeting vitals.

Feudal Japan – Tanto, wakizashi, katana – Tanto used for stabbing, katana capable of thrusting and slashing.

Middle East/North Africa – Jambiya, khanjar (curved daggers) – Curved blades created deep, ripping wounds.

Depiction Differences

Medical Care Was Rudimentary: Stab wounds to the chest or abdomen were almost always fatal without magical or extraordinary intervention. Infection from dirty blades was common and deadly.

Armor Matters: Chain-mail could deflect or absorb thrusts, making stabbing difficult without aiming at gaps (like armpits, groin, or neck).

Honor Duels and Assassinations: Many historical societies viewed stabbing in duels as less honorable than slashing, but it was more effective. Silent assassinations with poisoned daggers or concealed blades were common.

Example: A knight wounded by a dagger thrust under his mail at the armpit would face death not just from the blade itself, but from fever and infection in the days following.

Fantasy

Many fantasy worlds borrow heavily from medieval, renaissance, or ancient cultures to shape their weaponry.

Weapons Used

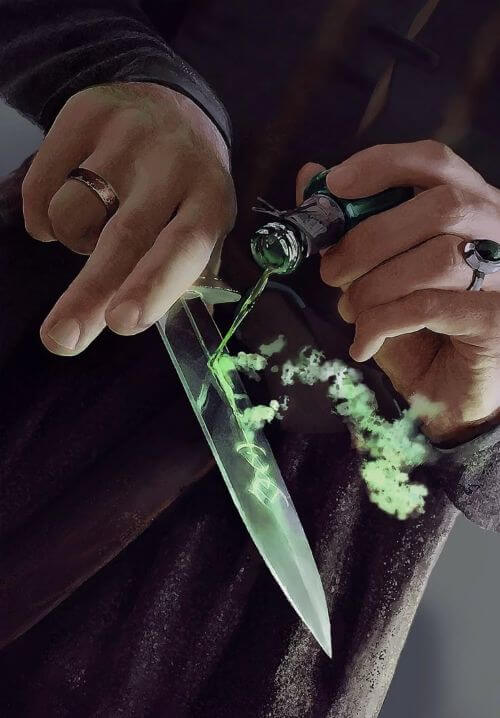

Daggers and short swords for assassins and rogues. Longswords, spears, and polearms for soldiers. Fantasy-specific blades like enchanted daggers, cursed swords, or living weapons.

Stabbing in Fantasy Battles

In formation battles (phalanx, shield wall), short stabbing weapons dominate—easier to use in tight spaces. Assassins and thieves in fantasy worlds often rely on stabbing unseen targets quickly and quietly.

Magical Considerations

A magical blade might prevent healing, cause additional magical damage (e.g., ice forming around the wound), or resist removal. Healing magic could close a stab wound externally but cannot fix internal organ damage unless very powerful. Armor enchantments might nullify or redirect a stab altogether.

Fantasy Genre Tips

Make wounds costly: Even in a world with magic, survival shouldn’t feel cheap or easy. Historical realism like armor vulnerabilities or battlefield tactics can ground even fantastical settings.

Example: A rogue wields an enchanted stiletto that prevents magical healing for 24 hours, causing a poisoned wound to fester unless the victim finds a rare cure.

Science Fiction

Even in worlds with blasters and plasma rifles, knives and swords often survive—because they are silent, efficient, and hard to defend against at close range.

Weapons Used

Monomolecular blades: Cut through most materials at the atomic level.

Vibroknives: Ultrasonic vibrating knives that inflict horrific wounds with minimal force.

Energy swords: Plasma or laser-based melee weapons that cauterize while cutting.

Stabbing Effects in Sci-Fi

Wounds may seal immediately (if cauterized) but cause severe internal organ trauma. Nano-augmented bodies may resist or adapt to stabbing injuries differently. Armor or synthetic clothing could deflect normal blades, requiring specialized weapons.

Medical Advances

Nanobots, regen-chambers, or biotech enhancements might heal wounds rapidly, but at a cost (e.g., reduced lifespan, increased mutation risks).

Example: A mercenary assassin uses a monomolecular dagger to sever a political target’s cybernetic spine – lethal, silent, and leaving barely a scratch visible on the surface.

Genre, historical context, and setting should heavily influence how you portray stab wounds in your story.

In a modern thriller, expect messy street fights and EMT rescues.

In a medieval war epic, armor and battlefield medicine (or lack thereof) dictate survival.

In fantasy, blending real-world weaponry and magical consequences enriches the world.

In science fiction, technology evolves the blade and how characters survive it.

Always ask:

What kind of blade would exist in this world?

How would armor, medicine, or magic change survival odds?

What emotional and physical scars would the wound leave behind?

Stab wounds can be the beginning of a story, the climax of a betrayal, or the mark of a character’s resilience.

Write them not just as injuries—but as turning points.

Treating Stab Wounds Across History (and Beyond)

Stab wounds have been a common battlefield and street injury for thousands of years, but how they’re treated depends on the era, location, and technology available. Across history, the treatment of stabbing injuries often meant a slow, painful, and uncertain recovery if survival was even possible. Meanwhile, fantasy and science fiction worlds open the door to magical or technological advances that dramatically reshape how a stab wound affects a story.

Whether it’s a Roman soldier packed with honey-soaked bandages, a modern-day survivor in an ER, a magical knight seeking a healing shrine, or a cyborg stitched back together by nanobots, a stab wound can define a moment of vulnerability, resilience, and transformation.

Make your characters bleed and heal in ways that deepen their journey. Because sometimes, surviving the wound is only the beginning of the story.

This guide walks you through typical treatments for stab wounds from ancient times through the Middle Ages to modern medicine and imagines how futuristic and fantasy worlds might handle these injuries.

Ancient World: Prayer, Poultices, and Hope

Typical Treatments

Basic Wound Cleaning: Wounds were often rinsed with wine, vinegar, or honey, substances believed to prevent infection (honey was actually effective).

Binding and Compression: Wounds were wrapped tightly with linen or wool strips soaked in oils or herbal mixtures.

Crude Surgery: Physicians might probe wounds with fingers or rudimentary tools to remove debris or clots. Stab wounds to the abdomen were often left open to drain. Sewing internal wounds was rare and largely unsuccessful.

Herbal Medicines: Plants like myrrh, garlic, and comfrey were used for pain relief and infection control.

Cauterization: Some wounds were burned shut with hot irons if bleeding couldn’t be stopped.

Spiritual Healing: Prayers and rituals were performed alongside physical treatments, especially in cultures that associate wounds with divine punishment.

Challenges

High infection rates.

Little understanding of internal injuries.

Pain management was extremely limited.

Example: An ancient warrior stabbed in battle might survive the initial wound but die days later of fever and sepsis despite the best treatment.

Medieval Times: Bloodletting, Amputation, and Battlefield Surgery

Typical Treatments

Immediate Field Dressing: Bleeding was stopped using cloths soaked in wine, vinegar, or even pitch (tar).

Bloodletting and “Balancing Humors”: Doctors often believed that purging “bad blood” could help to heal, sometimes making injuries worse.

Suturing: In some cases, larger wounds were stitched closed with linen thread and bone or bronze needles.

Poultices and Herbal Salves: Wounds might be packed with honey, crushed herbs (like yarrow), or moss to fight infection.

Amputation (in Severe Cases): If the wound became infected or gangrenous, amputation without anesthesia was a brutal but sometimes life-saving option.

Religious Interventions: People often saw healing prayers, relics, and pilgrimages as vital complements to physical treatment.

Challenges

Surgery was often deadlier than the wound.

No real antibiotics.

No understanding of sterility (surgeons reused bloody tools and did not wash hands).

Example: After a dagger wound during a medieval brawl, a knight might undergo a crude surgery by candlelight—with only mead for pain relief—then survive or die based on luck, not skill.

Contemporary Medicine: Trauma Care and Surgical Precision

Typical Treatments

Emergency Response: Pressure is immediately applied to stop bleeding. EMTs stabilize the patient for rapid transport to a hospital.

Hospital Treatment: Imaging (X-rays, CT scans) to assess internal damage. Surgical repair of blood vessels, organs, or muscle tissue. Sutures and stapling to close external and internal wounds.

Blood Transfusions: Rapid replacement of lost blood to prevent shock.

Antibiotics and Sterile Techniques: Preventing infection is a critical part of modern care.

Rehabilitation: After survival, patients often need physical therapy to regain strength and mobility.

Survival Rates

High for limb wounds and non-vital torso injuries with fast treatment.

Moderate to Low for deep chest, neck, or abdominal injuries without immediate surgery.

Example: A character stabbed in a mugging in a modern city might survive if someone applies pressure and calls 911 immediately, but they’ll still need surgery and weeks of recovery.

Science Fiction Treatments: Healing in the Future

Potential Treatments

Nanotechnology: Swarm bots enter the wound, seal blood vessels, rebuild tissue, and remove foreign bodies at the molecular level.

Regeneration Chambers: Stabbed characters are placed in bio-regenerative tanks that speed up natural healing – days of recovery in minutes.

Medical AI: Autonomous robots might diagnose and repair injuries faster and more accurately than human doctors.

Smart Bandages: Bandages embedded with biotech sensors and antibiotic dispensers manage wounds automatically and adjust pressure as needed.

Synthetic Clotting Agents: Injectable “liquid skin” or foam expands to fill and seal wounds internally.

Narrative Tensions Despite Technology

Healing may be expensive, unavailable to the poor, or restricted by politics.

Over-reliance on biotech might cause mutations, scarring, or psychological effects.

Medical treatment might be available—but only after the character survives long enough to reach it.

Example: A wounded bounty hunter staggers into a medbay. Nanofoam floods the stab wound, halting bleeding and regrowing torn muscle, but the memory of the attack stays with them.

Fantasy Treatments: Magic, Alchemy, and Healing Hands

Potential Treatments

Healing Magic: Spells might close the external wound instantly but cannot repair internal bleeding unless cast at a high level. Healing magic could require rare materials, such as phoenix feathers, holy water, or dragonroot.

Alchemical Salves: Potions and poultices that speed clotting or promote cellular regeneration but with side effects like fever, delirium, or magical scarring.

Clerical/Divine Healing: Priests and healers might invoke gods or spirits to heal wounds, but the patient must pay a spiritual price or perform a vow afterward.

Traditional Medicine: In low-magic settings, fantasy characters rely on herbal compresses, surgical stitching, cautery, and luck, much like historical counterparts.

Fantasy Complications

Cursed blades may leave wounds that refuse to heal.

Healing magic could fail if the wound was caused by dark magic or enchanted weapons.

Exotic anatomy (elves, dwarves, dragonkin) might require specialized healing knowledge.

Example: A ranger stumbles into a druid’s grove, stabbed by a cursed dagger. Ordinary healing spells cannot close the wound, forcing a desperate quest for an ancient elixir before infection or dark magic claims them.

Plot and Character Ideas

Stab wounds aren’t just dramatic, they’re deeply personal. Unlike gunshots, stabbings are usually close, violent, and intimate, meaning they often carry powerful emotional and psychological consequences for both attacker and victim. Whether it’s an act of betrayal, survival, or revenge, stab wounds can serve as pivotal plot points and character-defining moments.

Here’s a collection of plot and character ideas that use stab wounds as key drivers of story and character development.

The Survivor’s Guilt

Genre: Contemporary, Thriller

Plot Idea: A character survives a stabbing that kills a friend, family member, or teammate who tried to defend them.

Character Angle: They wrestle with survivor’s guilt, feeling they weren’t worth saving. They seek revenge against the attacker, despite being physically and emotionally scarred. They avoid relationships, convinced they are cursed and dangerous to others.

Twist: The deceased friend left a hidden message before dying, one the survivor only uncovers after grappling with their grief.

The Hidden Betrayal

Genre: Historical, Fantasy

Plot Idea: A character is stabbed by someone they trusted (a sibling, a friend, a fellow knight) during a political conspiracy or power struggle.

Character Angle: They must pretend not to know the truth to protect themselves and plot their revenge. The stab wound never properly heals, becoming a constant reminder of the betrayal. Trust becomes nearly impossible and future alliances are fraught with danger.

Example: A wounded prince wears his scar proudly, even as he plots the downfall of the courtier who tried to kill him.

The Stab That Wasn’t Supposed to Kill

Genre: Crime Drama, Urban Fantasy

Plot Idea: A young, inexperienced criminal stabs someone in a robbery gone wrong, only to discover the victim was critical to a bigger conspiracy.

Character Angle: They must decide whether to run, confess, or investigate the fallout. Their guilt and fear change them permanently, creating a redemptive arc or a descent into hardened criminality. They form an unlikely bond with someone tied to the victim (a sibling, a partner, an enemy).

Twist: The “victim” survives—but now wants revenge or blackmail instead of justice.

The Impossible Healer

Genre: Science Fiction, High Fantasy

Plot Idea: In a world where healing technology or magic is common, a character is stabbed by a weapon that prevents healing leaving them to slowly bleed out unless they find a rare, forbidden cure.

Character Angle: They must hide their injury while seeking a cure before time runs out. Every action becomes more desperate as their strength, sanity, or control slip away. They grow to understand the wider implications of the forbidden magic or tech that wounded them.

Example: A cybernetic knight stabbed by a monomolecular blade loses control of their body, turning them into a weapon against their own allies unless the wound is treated in time.

The Scar That Hides a Secret

Genre: Mystery, Urban Fantasy, Historical Fiction

Plot Idea: A character bears a stab wound scar from an attack they don’t remember. When the scar reacts (burns, aches, or glows), it triggers a mystery tied to their forgotten past.

Character Angle: They must investigate who they really are and why they were targeted. The scar acts as a map, a curse, or a key. Others recognize the scar, some as a sign of loyalty, others as a target.

Twist: The character was supposed to die in the original attack but was saved by an unknown benefactor with their own hidden motives.

The Trial by Blade

Genre: Fantasy, Historical Adventure

Plot Idea: A warrior culture has a tradition: young fighters must survive a ritual stabbing (non-lethal but painful) to prove their bravery or loyalty.

Character Angle: A character questions the tradition after being gravely injured or watching a friend die during the trial. They must decide whether to challenge the system or uphold it to earn their place. Their refusal (or survival) changes the culture’s future or sparks a rebellion.

Example: A princess disguises herself as a commoner to pass the trial, but the wound she receives threatens to expose her identity.

The Silent Assassin

Genre: Espionage, Science Fiction, Fantasy

Plot Idea: A professional assassin uses stabbing instead of guns because it’s silent and personal. Their latest assignment, however, goes wrong when the target survives.

Character Angle: The one who got away now hunts the assassin, forcing them to question their loyalty to their employers. They must choose whether to finish the job or switch sides. Memories of past kills resurface, tying them emotionally to their current prey.

Twist: The target and assassin were childhood friends or former comrades before fate set them against each other.

The Misjudged Hero

Genre: War Story, Post-Apocalyptic, Science Fiction

Plot Idea: People celebrate a wounded character as a hero for surviving a famous stabbing, but they fled, froze, or were accidentally stabbed.

Character Angle: They struggle under the weight of unearned glory. Someone from their past knows the truth and threatens to expose them. They must truly earn their title when a new threat arises.

Example: A soldier who accidentally survived a stabbing during a doomed battle must now lead survivors through an even deadlier conflict.

The Healing That Shouldn’t Have Worked

Genre: Dark Fantasy, Supernatural Horror

Plot Idea: After a mortal stabbing, a character is saved by mysterious magic or an ancient ritual but the healing changes them into something inhuman.

Character Angle: They struggle with physical mutations or uncontrollable powers born from the unnatural healing. They search for a cure while hiding the growing darkness inside. Their former allies either hunt them or use them as a weapon.

Twist: The only way to fully recover is to stab someone else in the same way, passing the curse onward.

The Family Blade

Genre: Fantasy, Historical Fiction

Plot Idea: A character inherits a sacred or legendary dagger only to be stabbed with it during a betrayal within their own family.

Character Angle: They must decide whether to forgive, avenge, or exile the betrayer. The blade’s lore and powers are connected to blood spilled within the family. Using the blade now comes at a terrible personal cost.

Example: The wound connects them to the spirits of past ancestors, some offering guidance, others demanding vengeance.

Stab wounds offer raw, visceral drama but they demand realistic handling to truly resonate. By considering anatomy, weapon physics, injury severity, and emotional aftermath, you’ll craft scenes that feel authentic and memorable. Stab wounds, not just injuries; they are story catalysts that can forge, fracture, or redefine a character’s destiny.

Remember: A knife changes a fight. A wound changes a life. Use stab wounds not just to injure your characters but to redefine them.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.