The Writer’s Guide to Psychological Trauma from Injuries

The broken bone, the blood, and the fever often take center stage when a character suffers a physical injury in a story. But many survivors of serious injuries will tell you that the psychological aftermath lasts far longer than the physical wounds.

For writers, portraying the emotional impacts, PTSD, and character reactions realistically not only adds depth but also honors the actual experiences of people who live with trauma. It turns injuries from onetime plot devices into ongoing character arcs.

What Is Psychological Trauma?

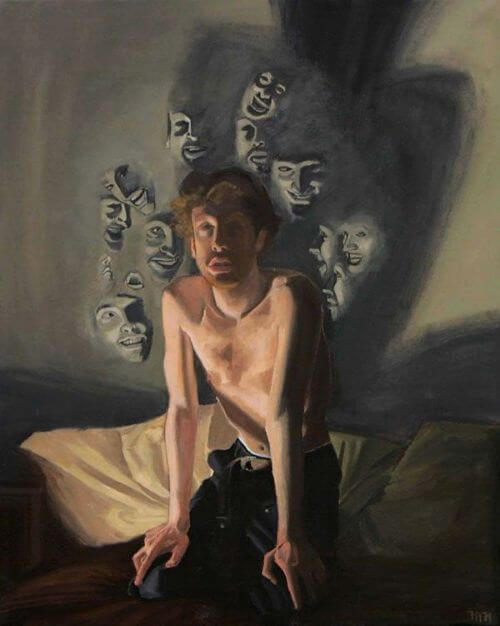

Psychological trauma is the emotional and mental response to an overwhelming event that threatens life, safety, or well-being. Injuries, especially violent or life-threatening ones, can trigger trauma responses long after the body heals.

Common forms in fiction include:

Acute Stress Reaction: Immediate panic, shock, or disassociation right after the injury.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): Long-term condition with flashbacks, nightmares, and hypervigilance.

Depression and Anxiety: Fear, guilt, or despair tied to loss of mobility, disfigurement, or sense of identity.

Emotional Affects of Injuries

Fear and Hypervigilance

Characters may avoid situations that remind them of their injury (a knight refusing to wear armor again, a driver terrified of cars after a crash).

Anger and Frustration

At themselves (“Why wasn’t I stronger?”) or others (“They left me behind”).

Frustration with long recovery periods or physical limitations.

Guilt and Survivor’s Guilt

Feeling unworthy for surviving when others did not.

Blaming themselves for the circumstances that caused the injury.

Shame and Identity Loss

Disfigurement or disability can create shame in societies that prize strength or beauty.

A soldier unable to fight, a dancer unable to perform, or a mage who loses their magic gestures may feel stripped of identity.

Numbness and Avoidance

Detachment from others, withdrawal from relationships, or using humor to mask deeper pain.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

PTSD can develop after violent injuries, near-death experiences, or medical trauma. Realistic symptoms include:

Intrusive Memories: Flashbacks, nightmares, or uncontrollable thoughts about the injury.

Avoidance: Staying away from reminders of the event (places, people, conversations).

Negative Thinking: Persistent guilt, self-blame, hopelessness.

Hyperarousal: Easily startled, irritable, trouble sleeping, feeling constantly “on edge.”

Important Note: PTSD is not the same for everyone. Some characters may become withdrawn; others may overcompensate by becoming reckless or aggressive.

Character Reactions to Trauma

Short-Term Reactions

Shock, denial, or disassociation.

Panic attacks or sudden bursts of tears or anger.

Long-Term Reactions

Struggles with recovery and adaptation.

Relationship strain (partners, friends, comrades not knowing how to help).

Unhealthy coping mechanisms (substance abuse, self-isolation, overwork).

Positive Adaptations

Some characters may channel trauma into growth, developing empathy, resilience, or a new purpose.

The Writer’s Toolkit

Don’t Rush Recovery: Trauma doesn’t vanish with one pep talk. Show gradual progress with setbacks.

Avoid Stereotypes: Not every injured soldier becomes angry, or every survivor becomes broken. Show unique reactions.

Show Daily Life Struggles: Fear of loud noises, difficulty sleeping, panic in crowds. These minor details make trauma feel real.

Use Relationships: Show how loved ones respond (supportive, dismissive, or overwhelmed) and how that shapes recovery.

Mix Visible and Invisible: A healed wound may leave no scar, but nightmares or flashbacks linger.

Example Scenarios

A firefighter who survived severe burns panics when near a stove flame, hiding his terror to maintain bravado.

A queen injured in an assassination attempt struggles to trust her own guards, leading to paranoia in court politics.

A soldier with a torn ligament hears a twig snap in the woods and reacts as if under attack, startling companions.

A space colonist wakes screaming from nightmares of a cryochamber malfunction, long after being rescued.

A (Very) Short History of Psychological Trauma

A sense of how people named and treated trauma over time will keep your story grounded.

Antiquity and Middle Ages

Ancient Near East and Greece/Rome: People viewed suffering after a catastrophe as divine punishment, imbalance of humors, or melancholy. Combat distress appears in texts (e.g., warriors with “panic,” sleeplessness). They did not cleanly separate the mind and body.

Classical medicine: The humoral model (black bile, yellow bile, blood, phlegm) explained mood and “nerves.” Treatments included diet, baths, music, philosophy.

Medieval Europe: People interpreted affliction as sin, demonic influence, or moral trial. Ritual, prayer, pilgrimage, and community care predominated. Somatic symptoms (fainting, tremors) were real but spiritualized.

Early Modern (16th–18th c.)

“Hysteria,” “vapors,” and “nervous disorders”: Doctors proliferated gendered diagnoses.

Battle and accident trauma: Recognized descriptively (nightmares, startle, palpitations), not categorized.

Treatments: rest cures, tonics, mesmerism, bleeding/purging (declining).

19th Century

Industrial/transport accidents: “Railway spine” (post-accident symptoms without obvious injury) put mechanical shock and mind–body debates into law courts.

Soldiers and colonials: “Irritable heart,” “neurasthenia,” and “shell shock” precursors in Boer and Crimean wars; moral judgments (cowardice vs. genuine illness) shaped care and stigma.

20th Century

World War I: Shell shock becomes a cultural flash point – tremors, mutism, nightmares. Responses ranged from rest to punishment to early talk therapies.

World War II and Korea: Combat fatigue/battle exhaustion; group psychiatry and forward treatment emphasized quick return to duty.

Vietnam era: Veteran activism + clinical research culminate in PTSD entering the DSM-III (1980). Trauma recognized beyond combat (disaster, assault, accidents).

Late 20th and 21st Century

Expanded lenses: Complex PTSD (chronic/interpersonal trauma), moral injury, vicarious trauma, TBI–PTSD overlap, somatic and exposure therapies, EMDR, pharmacology.

Global perspectives: Cultural syndromes and indigenous healing remind us that trauma narratives are culture bound (community ritual vs. individual diagnosis).

Contemporary discourse: Stigma declines but persists; social media, veteran advocacy, and survivor memoirs shape expectations of realism.

How Genre Shapes Depictions of Trauma from Injuries

Contemporary Fiction

Likely causes: vehicle accidents, assaults, fires, mass-casualty events, sports injuries, occupational disasters, combat and first-responder experiences, medical/ICU trauma.

Depictions

Language and care: Characters may use terms like PTSD, triggers, flashbacks, grounding techniques, therapy, meds. Show systems: ER to rehab, workplace leave, insurance barriers.

Symptoms with texture: sleep disturbance, hypervigilance, irritability, avoidance, guilt, somatic pain, panic, dissociation, intrusive memories – waxing/waning over time.

Social reality: Mixed reactions: supportive partners, minimizing bosses, online communities. Stigma and self-stigma matter.

Aftercare arc: Physical rehab intersects with therapy; relapse and plateaus are common. Recovery ≠ cure; functioning can improve while symptoms persist.

Writer Tips

Pace symptoms over weeks/months; let good days mislead characters.

Pair external stakes (trial, custody, job fitness test) with internal triggers.

Use sensory accuracy (smells, sounds, textures) to cue intrusions instead of labeling “he had a flashback.”

Historical Fiction

Likely causes: battlefield wounds, shipwrecks, plague/medical trauma, childbirth injuries, dueling, industrial accidents, riding and hunting mishaps.

Depictions

Period language: “Nervous disorder,” “soldier’s heart,” “melancholia,” “shell shock” (WWI), “distemper,” “moral weakness,” “possession.” Avoid anachronistic clinical terms.

Worldview: Clergy, barber-surgeons, apothecaries; explanations via humors, miasma, morality, or providence. Responses: rest cure, laudanum, tonics, water cures, religious ritual, exile to convalescence.

Social stakes: Honor, suspicion of malingering, class/gender biases. A noble’s “delicacy” may be indulged; a peasant’s “laziness” punished.

Writer Tips

Translate modern symptoms into period descriptions: sleeplessness, startlement, “the shakes,” “visions,” “spirit gone dim.”

Let period treatments help/harm: laudanum soothed nightmares but risks dependence; “rest cure” isolates and worsens despair.

Use institutions (regimental doctors, asylums) and diaries/letters to externalize an inner state consistent with the era.

Fantasy

Likely causes: maiming in battle, magical burns/poisons, mind-affecting curses, necromancy, forced geasa, near-death rituals, collateral damage from spell craft.

Depictions

Metaphor with rules: Curses function like trauma: recurring “echoes,” phobic geographies, memory-snare enchantments. Healing magic can close wounds yet not resolve fear/avoidance, or it transfers burden (healer absorbs echoes).

Cultural frames: Clan songs, temple rites, ancestor guidance as communal processing. Stigma may be “spirit-touched,” “omened,” or “unlucky.”

Limits of magic: Restoration spells heal flesh but leave moral injury (guilt over collateral deaths) or magical scars that trigger visions.

Writer Tips

Give magic trade-offs: a memory-cleansing rite also erases joy; protective wards numb both fear and love.

Build practices that mirror therapy (dream-walking, confession to a god, sword-forms as grounding) while staying in-world.

Science Fiction

Likely causes: hull breaches, cryo malfunctions, exosuit crush injuries, radiation burns, drone warfare guilt, cybernetic failures, alien biothreats.

Depictions

Futures of care: AI therapists, VR exposure labs, neuromodulators, memory editing, group therapy on long-haul ships, med-pods that fix bodies faster than minds.

New dilemmas: Is a memory redaction healing or erasure of self? Do synthetic limbs alter body image and identity? What if a ship’s black box replays trauma on loop?

Alien/cybernetics: Non-human psychologies (hive grief, color-based emotions), firmware “panic storms,” or trauma propagating across neural links.

Writer Tips

Keep consequences human: tech reduces suffering and creates ethical costs (access, consent, side effects).

Use setting-specific triggers (pressure doors hissing, hard vacuum silence) and practical barriers (therapy rationed on frontier worlds).

Practical Craft Notes (All Genres)

Show don’t label: Use concrete details: the fork clatter that spikes a startle response; the stitched scar the character won’t touch; the river they circle twice to avoid the bridge.

Arc design: Recovery is nonlinear. Interleave progress with setbacks; let victories be small (sleeping through the night, crossing a market square).

Relationships as mirrors: A partner who overprotects, a commander who doubts fitness, a friend who jokes to defuse. These dynamics externalize inner conflict.

Different kinds of wounds: Distinguish PTSD (intrusions/avoidance/hyperarousal) from depression, complicated grief, moral injury, and TBI. They can overlap but aren’t identical.

Avoid two pitfalls: The “instant cure” (a single talk, a spell, a gadget). The “trauma = personality” flattening. Let humor, competence, and desire coexist with symptoms.

Treatments for Psychological Trauma

The way societies understood and treated psychological trauma has shifted dramatically across time. From spiritual rituals to modern therapy, these approaches reveal not only medical practice but also cultural attitudes about injury, resilience, and the mind.

Ancient World (Pre-500 AD)

Trauma was often explained as divine punishment, imbalance of humors, or possession by spirits. Emotional suffering after battle or injury was described but rarely separated from physical causes.

Treatments

Spiritual rituals: Prayers, offerings, purification rites.

Philosophy: Stoics and other schools emphasized self-control and rational mastery over emotions.

Natural remedies: Herbal sedatives (opium poppy, wine, valerian root).

Community healing: Storytelling, music, and ritual feasts could restore social cohesion after collective trauma.

Limitations

No formal psychological care; trauma was endured or spiritualized. Those who failed to recover could be stigmatized as weak, cursed, or sinful.

Middle Ages (500-1500 AD)

Trauma symptoms (tremors, visions, muteness) were often seen as signs of sin, demonic influence, or madness.

Battlefield trauma was recognized but poorly addressed; “cowardice” was a common judgment.

Treatments

Religious intervention: Exorcism, confession, pilgrimage, relics.

Herbal remedies: Chamomile, lavender, St. John’s wort to “calm the spirit.”

Community support: Monasteries and religious orders sometimes sheltered the mentally unwell.

Isolation: Many trauma survivors were confined to “mad houses” or abandoned.

Limitations

Trauma was moralized or demonized; sympathetic care was rare and inconsistent.

18th and 19th Centuries

The rise of medicine reframed trauma as “nervous disorders,” “neurasthenia,” or “railway spine” (after train accidents).

Soldiers’ trauma was labeled “soldier’s heart” or “irritable heart.”

Treatments

Rest cures: Enforced bed rest, limited stimulation, isolation (popular for “nervous” women, often harmful).

Tonics and sedatives: Laudanum (opium), bromides, alcohol.

Asylums: Sometimes benevolent, often overcrowded and brutal.

Hydrotherapy: Baths, cold plunges, or showers believed to restore balance.

Talk therapy beginnings: Freud and others linked trauma to repression and memory.

Limitations

Treatments often reinforced stigma. Soldiers might be punished or forced back to battle. Women were especially pathologized.

Modern and Contemporary Medicine

Trauma is recognized as psychological and physiological: changes in the brain, nervous system, and stress response. PTSD became a formal diagnosis in the 1980s.

Treatments

Therapy: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), EMDR, exposure therapy, trauma-focused counseling.

Medication: SSRIs, anti-anxiety drugs, sleep aids.

Rehabilitation: Pairing psychological care with physical rehab after injuries.

Peer support: Veteran groups, trauma survivor communities.

Holistic approaches: Mindfulness, yoga, art therapy, animal-assisted therapy.

Challenges

Access, cost, stigma, and treatment-resistant cases.

Fantasy

Magical Healing

Memory-erasing spells: effective but may erase identity or love as well as pain.

Spirit-cleansing rituals: priests or shamans “draw out” nightmares or curses.

Dream-walking: healers enter a patient’s dreamscape to confront trauma directly.

Alchemical Remedies

Potions or charms that calm the mind, but risk dependency or side effects (hallucinations, magical corruption).

Cultural Practices

Warrior societies may use ritual storytelling, symbolic duels, or bonding ceremonies to reintegrate traumatized members.

Traumatized characters might be revered as “spirit-touched” or shunned as cursed.

Writer’s Tool: Decide whether magic masks trauma (suppresses symptoms) or truly heals it and what that costs.

Science Fiction

Treatments

Neurotechnology: Neural implants that dampen hyperarousal or delete traumatic memories. Risk erasing trauma erases identity, moral lessons, or relationships formed through suffering.

Virtual Reality Therapy: Controlled exposure in VR recreates traumatic events safely.

Nanomedicine: Nanobots recalibrate neurotransmitters, repairing “trauma pathways.”

AI Counselors: Virtual therapists available instantly, raising questions of empathy vs. programming.

Alien Treatments: Non-human species may “share” trauma communally, purge it through symbiosis, or view trauma as an honorable scar of memory.

Narrative Hook: Futuristic treatments create ethical dilemmas. Should trauma be cured instantly if it means losing part of yourself?

Plot and Character Ideas

The Sound of Glass

Genre: Drama

Plot Idea: After surviving a devastating car crash, a young teacher develops panic attacks whenever she hears breaking glass.

Character Angle: She hides her symptoms from colleagues to avoid pity, but her silence begins to isolate her.

Twist(s): A student accidentally shatters a beaker in class, triggering a flashback that exposes her secret and forces her to seek help.

The Firehouse Silence

Genre: Contemporary Thriller

Plot Idea: A firefighter who survived a warehouse collapse struggles with survivor’s guilt after fellow crew members died.

Character Angle: He throws himself into reckless rescues to prove his worth, endangering his team.

Twist(s): His reckless bravery isn’t courage, it’s an unconscious death wish, and a rookie must stop him before tragedy repeats.

The Soldier’s Tremors

Genre: Napoleonic War Drama

Plot Idea: A veteran returns from Waterloo, plagued by nightmares and trembling fits described as “soldier’s heart.”

Character Angle: His family views him as broken; he wrestles with honor versus shame in a society that has no name for trauma.

Twist(s): His episodes reveal details of the battle others have missed, making him both unreliable and uniquely valuable as a witness.

The Asylum Letter

Genre: 19th-Century Gothic

Plot Idea: A woman institutionalized for “nervous disorder” after a carriage accident secretly writes letters detailing her vivid nightmares and hallucinations.

Character Angle: Powerless in the asylum, her writing becomes both rebellion and survival.

Twist(s): Her letters are smuggled out and inspire public debate that could change asylum practices.

The Mage’s Echo

Genre: Epic Fantasy

Plot Idea: A battle-mage barely survives a magical explosion but is haunted by “echoes” of fire and screams that return whenever he channels magic.

Character Angle: Once proud of his power, he now fears using it, leaving his companions vulnerable.

Twist(s): The echoes aren’t hallucinations, they are trapped souls, crying to be freed.

The Scarred Queen

Genre: Political Fantasy

Plot Idea: An assassination attempt leaves a young queen both scarred and terrified of court gatherings.

Character Angle: Her paranoia alienates allies and feeds rumors of weakness.

Twist(s): Her fear saves her. When she refuses to attend a feast, her absence thwarts another assassination plot.

The Broken Blade

Genre: Dark Fantasy

Plot Idea: A warrior who lost comrades in a failed siege cannot bear the sound of clashing steel, breaking down in battle.

Character Angle: He drinks to numb himself but secretly longs for redemption.

Twist(s): The enemy exploits his trauma, using war drums tuned to trigger his panic.

Cryo Dreams

Genre: Space Survival

Plot Idea: A colonist pulled from malfunctioning cryosleep experiences vivid hallucinations of suffocation and freezing.

Character Angle: Struggling to adapt on the new planet, she doubts whether her visions are trauma or a warning from the ship’s damaged AI.

Twist(s): The “hallucinations” turn out to be fragments of other colonists’ minds, bleeding into hers.

Neural Ghosts

Genre: Cyberpunk Noir

Plot Idea: A mercenary with a cybernetic arm is haunted by phantom pain and flashbacks of the ambush that cost him his limb.

Character Angle: He numbs himself with neuro-stims, jeopardizing missions.

Twist(s): His trauma isn’t just in his head. The cybernetic implant is replaying stored sensory data from the ambush.

The Void Between

Genre: Space Opera

Plot Idea: A starship pilot survives a hull breach but becomes hypervigilant, panicking whenever he hears the hiss of airlocks.

Character Angle: Once fearless, he now hesitates in combat, endangering his crew.

Twist(s): His paranoia proves right: the ship’s seals really are being sabotaged.

Ashes of the Stage

Genre: Contemporary/Fantasy Blend

Plot Idea: A stage performer injured in a pyrotechnics accident develops PTSD around fire, complicated when he discovers he has latent fire magic.

Character Angle: Torn between fear and destiny, he must master the very element that terrifies him.

Twist(s): His magic is tied to his trauma. He can only control it when facing his worst memories.

The Healer’s Burden

Genre: Fantasy/Sci-Fi Hybrid

Plot Idea: A battlefield medic develops psychological trauma from watching too many patients die despite advanced healing tools.

Character Angle: Known as compassionate and tireless, she secretly considers abandoning her duty.

Twist(s): Her trauma is weaponized. An enemy uses illusions of her past patients to paralyze her in combat.

Psychological trauma reminds readers that injuries don’t end with the scar. The emotional weight of fear, anger, guilt, or PTSD can be more transformative than the physical injury itself. When written with care and accuracy, trauma becomes a tool for character growth, conflict, and empathy, one that grounds even the most fantastical stories in deeply human truth.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.