The Writer’s Guide to the Long-term Effects of Injuries

When a character survives an injury in fiction, that’s often where the story ends. The hero limps off into the sunset or awakens in a hospital bed, battered but triumphant. Yet for real people, recovery doesn’t stop when the bleeding does. It continues for months or years afterward.

The long-term effects of injury – chronic pain, fatigue, mobility limitations, and psychological adjustment – offer rich opportunities for character depth, realism, and emotional stakes. Portraying them accurately can turn a one-dimensional hero into a living, breathing survivor.

What Happens After “Healing”?

Even when bones knit, tendons reattach, or skin scars over, the body doesn’t always return to what it was before. Pain, stiffness, and weakness can linger long after the visible wound is gone. The severity, type, and location of the injury determine what kind of long-term impact your character lives with.

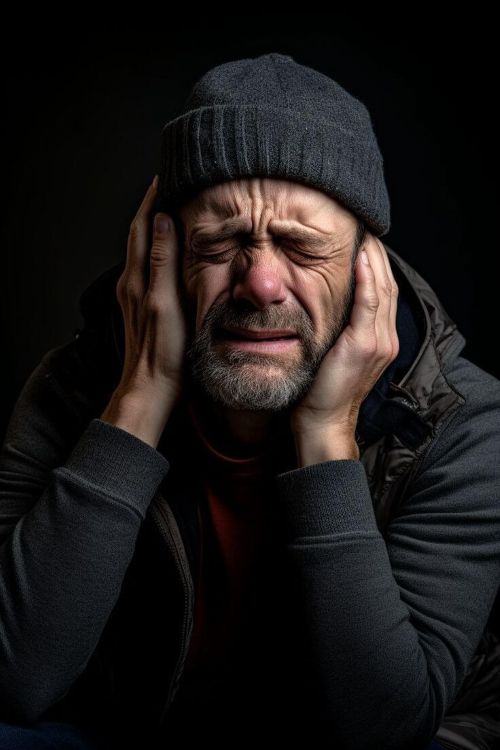

Chronic Pain: The Lingering Companion

Pain that persists for months or years after the initial injury has healed. It may stem from nerve damage, scar tissue, or chronic inflammation.

How It Feels

Constant dull ache or sharp shooting pain.

Weather sensitivity (worse in cold or damp conditions).

Random flare-ups that strike without warning.

Sleep disruption, irritability, and exhaustion.

Writing Tips

Chronic pain fluctuates. Some days are manageable, others unbearable.

Show adaptation: careful movements, altered gait, habitual stretching, grimaces.

Use internalization: pain erodes patience and focus, making simple tasks monumental.

Example: A retired knight massages his shoulder each morning before strapping on armor, knowing the old wound will ache by noon but doing it anyway because duty demands it.

Energy Levels and Fatigue

Healing consumes energy. Chronic pain, inflammation, or nerve damage can leave a body constantly exhausted. Pain meds, depression, or lack of restorative sleep compound it.

How It Appears

Struggling to concentrate.

Taking frequent breaks.

Sleeping long hours but never feeling rested.

Short temper or zoning out mid-conversation.

Writing Tips

Fatigue reshapes daily life: errands take twice as long, plans get canceled, and guilt sets in.

Show characters learning their limits: pacing themselves, conserving energy (“spoon theory” for chronic illness is a useful reference).

Example: A once tireless ranger now times every movement; scaling a small hill takes strategy, not strength. He saves energy for the moments that count.

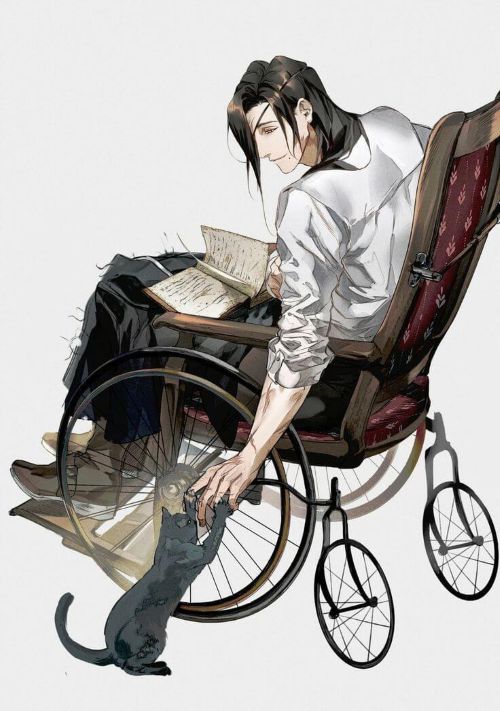

Mobility and Physical Adaptation

Varying Severity

Mild: Occasional stiffness or slight limp.

Moderate: Requires cane, brace, or regular rest.

Severe: Wheelchair, prosthetic, or total loss of function.

Challenges

Navigating stairs, terrain, or uneven ground.

Carrying items while using mobility aids.

Pain or fatigue triggered by overexertion.

Emotional and Social Coping

Common Reactions

Frustration and grief over lost abilities.

Anxiety about dependence or burdening others.

Changes in self-image or identity.

Isolation if others underestimate or pity them.

Positive Coping

Finding new purpose or adapting old skills.

Humor as resilience.

Supportive relationships and community.

Unhealthy Coping

Overcompensation, denial, or self-neglect.

Substance abuse or isolation.

Internalized shame or bitterness.

Writing Tips

Recovery isn’t linear: your character might alternate between acceptance and despair.

Use relationships to reflect healing: friends who understand vs. those who don’t.

Avoid the “magical recovery” trope unless there’s a strong worldbuilding reason.

Research lived experiences. Look for blogs, interviews, or memoirs from people with similar injuries.

Focus on sensory detail. Pain isn’t generic. Describe its rhythm, texture, and emotional echo.

Don’t rush the timeline. Physical recovery can take years, and emotional recovery often longer.

Show adaptation over inspiration. Readers connect more deeply when resilience feels practical, not saintly.

Weave in humor and normalcy. Even in chronic pain, people laugh, love, and build lives.

Show realistic adjustments: sitting to work, altering fighting styles, building routines around accessibility.

Avoid framing disability as tragedy or inspiration alone. Show it as life, with humor, frustration, and adaptation.

Remember: mobility aids are tools of independence, not symbols of defeat.

Examples

A modern soldier with a spinal injury learns to navigate civilian life, finding new purpose training service dogs.

A medieval blacksmith with a crushed hand crafts one final masterpiece: a prosthetic tool that lets him forge again.

A space pilot with a nerve injury must rely on an AI co-pilot but struggles to trust the machine that replaced his instincts.

A fantasy archer loses mobility after a cursed wound; her solution is to bond with a magical hawk who becomes her eyes and hands in battle.

Depicting the Long-Term Effects of Injuries Across Genres

The aftermath of injury doesn’t end when the bleeding stops. Whether your story is set in a modern hospital, a medieval battlefield, or a starship far from home, the long-term effects (pain, fatigue, and adaptation) will shape both your characters and your world. How those effects are perceived, managed, and narrated depends heavily on genre and setting.

Contemporary Fiction

How They Occur

Car crashes, workplace accidents, sports injuries, chronic illnesses, and military wounds.

Injuries caused by trauma, violence, or medical complications (burns, amputations, spinal damage).

Depiction Notes

Modern readers expect realism: accurate recovery timelines, physical therapy, medical management, and social implications (insurance, accessibility, stigma).

Chronic pain and fatigue are invisible to outsiders. Characters may face disbelief or dismissal (“But you look fine”).

Mobility aids, prosthetics, and adaptive technology are normalized but can still carry emotional weight.

Social Dynamics

Support networks (family, partners, therapy, online communities) help recovery but can also create dependency conflicts.

Some characters hide their pain to maintain independence; others overcompensate through work or perfectionism.

Narrative Use

Focus on how the injury reshapes daily life and identity.

Depict moments of quiet endurance rather than melodrama: choosing an elevator over stairs, canceling plans on flare-up days, laughing through frustration.

Example: A marathon runner learning to live with a prosthetic leg discovers that recovery isn’t just physical, it’s learning to accept help and redefine what “strong” means.

Historical Fiction

How They Occur

War injuries (sword cuts, cannon blasts, burns).

Labor accidents, riding falls, childbirth injuries, infections, amputations.

Depiction Notes

Limited medical care means many injuries lead to permanent impairment.

Crude prosthetics, untreated nerve damage, and infection create lifelong complications.

Chronic pain and fatigue are common, though rarely diagnosed as such.

Social Dynamics

Disability is often tied to moral, spiritual, or class-based ideas:

A “crippled” soldier may be seen as brave yet pitiful.

A laborer unable to work becomes a financial burden.

A noblewoman’s limp might be hidden to preserve marriage prospects.

Religious or superstitious interpretations abound: pain as divine punishment, suffering as penance, or miraculous survival as proof of favor.

Narrative Use

Injuries can become metaphors for societal change: the broken knight who symbolizes the cost of endless war, the midwife who continues her work despite her own damage.

Emphasize adaptation within limitation: crafting new tools, relying on community, or finding purpose beyond physical labor.

Example: A wounded Napoleonic soldier returns home with a mangled arm. His struggle isn’t just physical, it’s surviving in a society that venerates heroes but forgets the maimed.

Fantasy

How They Occur

Battle wounds, magical injuries, curses, transformations, or long-term consequences of healing gone wrong.

Depiction Notes

Fantasy allows exploration of how magic intersects with recovery:

Healing spells may close wounds but leave nerve pain, stiffness, or magical “scars.”

Potions may suppress pain at the cost of addiction or side effects.

Divine healing could cure the body but not the mind, leaving lingering trauma.

The world’s culture shapes response: a limping warrior might be pitied in one kingdom and revered as blessed in another.

Social Dynamics

Magical prosthetics, enchanted braces, or sentient limbs could change what “disability” means.

Chronic pain might manifest as literal energy drain: fatigue that seeps magic or disrupts spellwork.

Supernatural coping mechanisms could mirror real-world ones: meditation becomes mana-balancing, herbal teas become enchanted tonics.

Narrative Use

Explore themes of power and loss: how a hero copes when magic can’t fix everything.

Healing magic’s limitations make the world feel grounded and morally complex.

Injuries can shape character development, turning warriors into teachers, or mages into philosophers.

Example: A battle mage, permanently weakened by a cursed burn, learns to wield quiet magic of restoration instead of destruction, becoming the mentor the next generation needs.

Science Fiction

How They Occur

Industrial accidents in colonies, space combat injuries, radiation exposure, neural or cybernetic trauma.

Depiction Notes

Medical technology can mitigate, but not erase, long-term effects:

Cybernetic prosthetics restore mobility but alter body image and identity.

Neural implants reduce pain but risk personality shifts or malfunction.

Cryogenic repair saves lives at the cost of lingering fatigue or sensory distortion.

Pain management might involve AI-monitored medication or nanobots that adjust neurotransmitters.

Social Dynamics

Disabilities might carry new social meanings: enhanced vs. unmodified, biological vs. mechanical.

Societies with instant healing tech may view unhealed characters as choosing to live with imperfection, a potential source of stigma or rebellion.

Narrative Use

Explore ethical questions: what happens when pain and weakness can be engineered out of existence?

Injury and augmentation can blur identity. What’s left of the “original” person when half the body is replaced?

Use the futuristic setting to parallel modern issues like accessibility, bodily autonomy, and chronic illness.

Example: A starship engineer with neural implants that suppress pain starts experiencing phantom sensations: memories of pain encoded in the circuitry itself.

Treatments for Long-Term Effects of Injuries Through History and Across Genres

How people treat long-term injuries reveals just as much about a society as how they fight their wars or heal their wounds. From herbal salves and superstition to physical therapy and neural implants, every era and world deals with chronic pain, fatigue, and mobility in its own way. But for your characters, the truest test isn’t whether their pain is cured, it’s how they live with what remains. Chronic injury and long-term effects remind readers that survival is never free; it’s an act of ongoing adaptation and strength.

Ancient Times

The concept of healing was deeply tied to religion and balance. Chronic pain and disability were often seen as divine punishment, fate, or imbalance of the body’s natural forces. Ancient physicians and healers understood that some injuries never truly healed and their remedies aimed to soothe, not cure.

Treatments

Herbal medicine: Willow bark (natural aspirin), opium poppy, and myrrh were used to dull pain.

Heat and massage: Egyptians and Greeks used hot stones, oils, and stretching for stiffness.

Hydrotherapy: Baths in sacred springs or mineral pools were believed to restore strength.

Religious and ritual healing: Offerings to Asclepius, prayers, charms, and amulets for divine intervention.

Narrative Insight

In an ancient setting, long-term pain might be viewed as a sacred mark (proof of surviving the gods’ test) or as a curse that isolates the character. Survival is a balance between endurance and faith.

The Middle Ages

Physical ailments were often seen as spiritual tests or punishments. Medicine relied on the theory of humors: balancing blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Chronic conditions were rarely differentiated from acute illness. If an injury didn’t heal, it was accepted as permanent.

Treatments

Poultices and salves: Honey, vinegar, and herbal pastes to ease inflammation.

Bloodletting and leeches: Used to “rebalance” the body.

Faith-based healing: Pilgrimages to shrines of saints, holy water, relics, and prayer circles.

Primitive mobility aids: Crude crutches, carved wooden canes, or slings.

Community care: Monasteries often provided long-term shelter and basic care for the disabled.

Narrative Insight

Pain and impairment might earn pity or suspicion of witchcraft or demonic influence. A maimed knight might retire to a monastery; a peasant might be left to beg. Writers can show resilience in characters who find new identity or purpose in a world with little sympathy.

18th and 19th Centuries

The Enlightenment introduced anatomy, surgery, and early rehabilitation. The Industrial Revolution increased accidents, creating awareness of “invalids” and long-term recovery. Medical science began to recognize pain management, though addiction and poor sanitation were rampant.

Treatments

Opioids and laudanum: Common painkillers prescribed freely, often leading to dependence.

Physical therapy: Began emerging in the late 19th century, often used for soldiers and accident victims.

Hydrotherapy and mineral spas: Popular “cures” for stiffness and exhaustion.

Prosthetics: Wooden limbs, iron braces, and early mechanical aids became more sophisticated after each war.

Rest cures: Long periods of enforced bed rest (especially for women), often worsening muscle loss and depression.

Narrative Insight

This era offers stark contrasts: mechanical innovation meets medical ignorance. A war veteran may have a crude prosthetic but no understanding of chronic pain; a Victorian lady may be sedated rather than treated. There’s rich opportunity to show how survival collides with social expectation.

Modern and Contemporary Medicine

The 20th and 21st centuries reframed chronic conditions as manageable rather than shameful. Medical care now recognizes the link between physical injury, chronic pain, and mental health.

Treatments

Pain management: Opioids (carefully monitored), NSAIDs, nerve blocks, acupuncture, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS).

Physical and occupational therapy: Strengthening, balance training, ergonomic tools.

Surgery: Joint replacements, nerve grafts, and advanced prosthetics.

Mental health support: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), mindfulness, trauma counseling.

Assistive technology: Wheelchairs, braces, adaptive software, prosthetic limbs with neural feedback.

Lifestyle management: Pacing, exercise, sleep regulation, and community support.

Narrative Insight

Modern characters can realistically live full, complex lives with chronic conditions, balancing independence and adaptation. The tension lies not in survival, but in perseverance, identity, and relationships.

Fantasy

Healing may be magical, alchemical, or divine but that doesn’t mean it’s perfect. A world’s magic system dictates whether long-term pain exists and if it does, why.

Treatments

Magical Healing: Instant regeneration spells might close wounds but leave “soul scars” or magical exhaustion. Healing potions suppress symptoms temporarily, with addiction or diminished effect over time.

Divine Intervention: Miracles granted only to the worthy or the wealthy create class tension and moral dilemmas.

Herbal Alchemy: Complex brews for pain relief, energy restoration, or muscle repair; side effects might include hallucinations or reduced magic power.

Runic or Elemental Therapy: Element-based treatments: heat from fire mages for stiffness, water mages restoring circulation, air mages easing breath and fatigue.

Narrative Insight

Fantasy allows exploration of cost and consequence: what if a hero refuses magical healing to retain humility? What if divine healers charge a soul debt for restoring mobility? Chronic pain in a magical world can serve as metaphor for inner scars and the limits of even great power.

Science Fiction

Future medicine may blur the line between human and machine. With gene editing, nanotechnology, and neural engineering, long-term effects might be treatable but at an ethical price.

Treatments

Cybernetic Prosthetics: Integrate with the nervous system for natural control but risk phantom feedback or identity crises.

Nanobot Repair Systems: Constantly monitor and mend tissue damage but require maintenance or AI oversight.

Neural Recalibration: Devices that regulate pain perception or energy but risk emotional blunting.

Cryogenic or Stem-Cell Regeneration: Regrows tissue but drains metabolic energy or ages other organs.

AI-Driven Rehabilitation: Personalized therapy delivered by synthetic caretakers, efficient but emotionally hollow.

Plot and Character Ideas

The Weight of Rain

Genre: Contemporary Drama

Plot Idea: A construction worker develops chronic back pain after an on-site accident and struggles to adjust to life behind a desk. His identity as a provider and “hands-on man” begins to crumble.

Character Angle: Stoic and practical, he hides his pain from his family, creating emotional distance just when they need him most.

Twist(s): When his teenage son joins the same company, the father must confront his pride and finally speak about what living in constant pain has cost him.

A Song for the Winter Sea

Genre: Historical Fiction (19th Century Whaling Era)

Plot Idea: A harpooner who loses his leg to a whale attack joins a ship as a sea shanty singer, using music to mask his pain and regain belonging among the crew.

Character Angle: His voice steadies the men at sea, but every storm reminds him of the scream he never uttered.

Twist(s): When a mutiny brews, his songs, once morale boosters, become coded messages to save loyal men from slaughter.

The Iron Dancer

Genre: Contemporary Romance

Plot Idea: A ballerina suffers a devastating ankle injury that ends her performance career. Forced into teaching, she must rediscover joy through others’ movement.

Character Angle: Obsessed with perfection, she measures her worth by grace until a student with cerebral palsy challenges her definition of beauty and movement.

Twist(s): The student’s unconventional dance wins international acclaim under her choreography, not her spotlight.

The Knight of the Broken Step

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A legendary knight survives a dragon’s flame but is left with a burned and weakened leg. Dismissed from service, he becomes a mentor to squires training for a war he can no longer fight.

Character Angle: He hides behind bitterness until his students face the same dragon and need his tactical mind, not his sword arm.

Twist(s): The dragon remembers him and spares the squires in recognition, turning his defeat into redemption.

Glass Nerves

Genre: Science Fiction / Cyberpunk

Plot Idea: A pilot fitted with cybernetic limbs after a crash begins experiencing phantom sensations – pain, cold, even “touch” – from the old flesh that’s gone.

Character Angle: Torn between gratitude for survival and horror at losing bodily autonomy, they begin to suspect the prosthetics’ neural interface records emotions.

Twist(s): The sensations aren’t memories, they’re feedback from someone else who used the same parts before.

The Seamstress of Ashfield Hall

Genre: Gothic Historical

Plot Idea: A governess badly burned in a house fire hides her scars beneath lace and high collars. As she teaches her employer’s daughter, whispers claim she was the fire’s cause.

Character Angle: Her physical pain mirrors her shame; she becomes obsessed with protecting the child to prove her worth.

Twist(s): The girl’s father was responsible for the blaze and has been using her disfigurement as his alibi.

Emberlight

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A fire mage loses control of his magic, permanently scorching his hands. Unable to cast safely, he apprentices under a healer who teaches him to channel warmth into restoration rather than destruction.

Character Angle: Once proud and feared, he wrestles with humility and fear of relapse.

Twist(s): His pain isn’t just physical. The burn itself stores unstable magic that could reignite under emotional stress.

The Cartographer’s Hand

Genre: Steampunk Adventure

Plot Idea: A famous mapmaker loses his dominant hand in an airship accident. Desperate to keep his reputation, he builds an intricate mechanical replacement.

Character Angle: His obsession with precision becomes literal. He cannot accept imperfection, even in his human heart.

Twist(s): The maps he draws with the mechanical hand reveal secret routes unseen by the human eye, possibly a connection between machine and otherworldly forces.

Beneath the White Noise

Genre: Contemporary Psychological Thriller

Plot Idea: After surviving an explosion, a journalist suffers from tinnitus and partial hearing loss. The constant ringing drives her to obsession as she investigates the incident.

Character Angle: Isolated from sound and sanity, she begins to hear patterns in the ringing, messages no one else can.

Twist(s): The sound is real: hidden transmissions from those responsible for the explosion.

The Weightless Soldier

Genre: Science Fiction / Military

Plot Idea: A paratrooper injured in atmospheric combat loses bone density due to zero-gravity recovery. Despite cybernetic reinforcement, he’s forbidden from re-deployment.

Character Angle: Built for battle but exiled to logistics, he must redefine purpose in a military that reveres strength.

Twist(s): When sabotage threatens his ship, his light frame, once a weakness, lets him navigate spaces others can’t, saving the crew.

The Singer and the Scar

Genre: Historical Fiction (WWI)

Plot Idea: A wartime nurse who inhaled mustard gas loses her voice but becomes a composer, transforming her pain into music that captures the soul of a generation.

Character Angle: Once the life of the ward, she now communicates through melody instead of words.

Twist(s): Her symphony, meant as requiem, becomes a national anthem for peace, forever linking her name to both suffering and healing.

The Long March Home

Genre: Epic Fantasy

Plot Idea: A warrior queen survives a devastating arrow wound that leaves her unable to ride or fight. As her realm faces rebellion, she must lead from her sickbed through diplomacy, intelligence, and moral authority.

Character Angle: Used to command through fear, she now learns to wield compassion and trust.

Twist(s): The arrowhead was cursed. It slowly turns to iron within her body. When the curse reaches her heart, she uses its final pulse to forge a binding treaty.

Long-term injuries test endurance in every sense: physical, mental, and emotional. When written with nuance, they become more than a limitation; they are a living part of who your character is.

By showing chronic pain, fatigue, and adaptation honestly, you remind readers that healing isn’t about returning to who we were, it’s about learning to live fully in who we’ve become.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.