The Writer’s Guide to Healing Herbs and Other Treatments

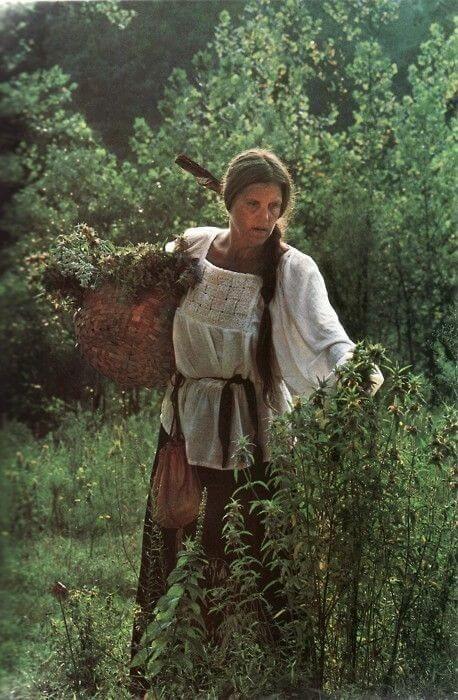

Before antiseptics, antibiotics, and modern surgery, healers relied on the natural world to treat wounds and illnesses. Herbs, roots, resins, and animal products formed the foundation of medicine from ancient Egypt through the 19th century, and they still appear in fantasy, historical, and even post-apocalyptic fiction. When written accurately, herbal medicine can lend authenticity to your world-building and depth to your characters, showing how they interact with the limits of their time.

Understanding Herbal Medicine

For most of history, medicine was based on observation and tradition, not scientific testing. Some remedies genuinely helped, others worked by coincidence or placebo, and some were outright harmful.

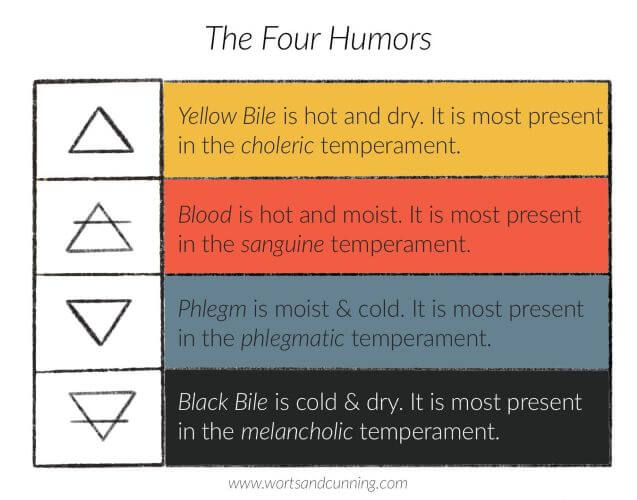

The ancient and medieval world believed in the theory of humors: that health depended on balancing four fluids: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. Illness came from imbalance, and treatments aimed to restore equilibrium through purging, bloodletting, or balancing “hot” and “cold” herbs.

While the humoral theory was incorrect, many of the herbs used in those treatments had real medicinal properties and modern medicine still uses compounds derived from them today.

Herbal Preparations

Writers often confuse teas with tinctures or poultices. Here’s a quick guide to keep your herbal realism on point.

Infusion (Tea)

Extraction using hot water.

Pour boiling water over herbs, steep, and strain.

Gentle internal treatments (digestion, relaxation).

Decoction

Stronger water-based extraction using boiling.

Boil roots, bark, or tough herbs 10–30 min.

Used for fever, pain, or energy restoration.

Tincture

Alcohol-based extract preserving active compounds.

Soak herbs in alcohol or vinegar for weeks.

Concentrated medicine, small doses for long-term use.

Poultice

Warm, moist mass of crushed herbs applied directly to skin.

Mash herbs and apply them to wounds or sprains.

Draws out infection, soothes inflammation.

Salve/Ointment

Oil- or fat-based preparation.

Infuse herbs in oil, mix with beeswax.

Protects wounds, moisturizes skin.

Liniment

Liquid rubbed into skin for sore muscles or joints.

Mix herbs with alcohol, vinegar, or oil base.

Pain relief, muscle stiffness.

Syrup

Sweet medicinal solution.

Combine herbal decoction with sugar or honey.

Masks bitter herbs; used for coughs or children.

Common Historical and Fantasy-Friendly Remedies

Honey

Use: Applied to wounds, burns, and infections.

Preparation: Used raw or mixed with herbs; sometimes spread on linen dressings.

Scientific Value: Honey is antibacterial and antifungal because of its acidity, hydrogen peroxide content, and ability to draw out moisture from bacteria.

Usefulness: Legitimate. Modern medicine still uses medical-grade honey (especially Manuka honey) for burn and wound treatment.

Garlic

Use: Antiseptic, used in poultices and tonics.

Preparation: Crushed and applied to wounds or eaten to “purify the blood.”

Scientific Value: Contains allicin, a real antibacterial compound.

Usefulness: Effective in mild antibacterial and antifungal applications; overuse may irritate skin or stomach.

Willow Bark

Use: Pain relief, fever reduction.

Preparation: Brewed as tea or chewed raw.

Scientific Value: Contains salicin, precursor to aspirin.

Usefulness: Highly effective, one of history’s most successful herbal remedies.

Aloe Vera

Use: Soothes burns, skin irritations, and wounds.

Preparation: Gel from the fresh plant applied topically.

Scientific Value: Proven to reduce inflammation and aid healing.

Usefulness: Safe and effective, still used today.

Lavender and Chamomile

Use: Calm nerves, promote sleep, and soothe pain.

Preparation: Infused in teas, oils, or poultices.

Scientific Value: Mild sedatives; lavender oil also has antibacterial effects.

Usefulness: Genuinely soothing; effective for mild anxiety or insomnia.

Comfrey (also known as “Knitbone”)

Use: To help broken bones, bruises, and wounds heal faster.

Preparation: Made into poultices or ointments.

Scientific Value: Contains allantoin, which encourages cell growth but also toxic alkaloids if ingested.

Usefulness: Safe for topical use on unbroken skin; effective for bruises and sprains but potentially harmful internally.

Yarrow

Use: Stops bleeding and reduces inflammation.

Preparation: Leaves crushed or made into poultices, tinctures, or teas.

Scientific Value: Antimicrobial and astringent properties verified.

Usefulness: Effective as a mild antiseptic; “soldier’s woundwort” in several cultures for good reason.

Elderflower and Echinacea

Use: Colds, fevers, and immune support.

Preparation: Brewed as teas or tinctures.

Scientific Value: Mild immune-modulating and anti-inflammatory effects.

Usefulness: Helpful for mild infections or inflammation, though not a cure-all.

Foxglove (Digitalis)

Use: Historically for heart ailments.

Preparation: Powdered or steeped leaves (dangerous without dose control).

Scientific Value: Contains digitalin, used in modern heart medicine.

Usefulness: Effective in minute doses, deadly in large ones. Excellent for dramatic fiction but risky.

The Usefulness (and Limits) of Herbal Medicine

What Worked

Many herbal treatments have measurable pharmacological effects: pain relief (willow), antibacterial action (honey, garlic), calming (lavender, chamomile), and skin healing (aloe).

They provided comfort and care when modern medicine didn’t exist.

What Didn’t

Humoral theory: The belief that balancing hot/cold, wet/dry humors could cure illness was false.

Lack of sterility: Contaminated bandages and tools often caused more harm than help.

Guesswork in dosing: Effective herbs (like foxglove or hemlock) could kill without precise measurement.

Superstition: Magical thinking sometimes replaced genuine care.

In fiction, a healer’s herbal craft can show intelligence, empathy, and cultural depth, even when she doesn’t understand the science behind her remedies. A few accurate herbs and preparations go a long way toward world-building realism.

Remember: in many settings, belief in the treatment mattered as much as the treatment itself.

For Fantasy and Historical Fiction

Blend real herbs with invented ones to expand your world organically (“moonleaf” with antiseptic glow, “ironroot” for bone healing). Consider scarcity. Some herbs may grow only in specific regions, making them valuable plot elements.

In worlds with magic, healing herbs may amplify or stabilize spell work rather than replace it.

Example: A healer brews an infusion of yarrow and comfrey to treat a soldier’s wound, then adds a drop of phoenix ash to awaken the herbs’ dormant magic. The result heals flesh but scars the soul, an ancient trade-off forgotten by most.

For Science Fiction Writers

Herbal medicine might experience a renaissance on colony worlds where modern pharmaceuticals are scarce. Genetic engineering or biofabrication could resurrect extinct medicinal plants or create new hybrids. Alien botanicals may function unpredictably: a flower that heals humans but poisons androids, or vice versa. “Traditional medicine” might coexist with AI diagnostics, creating tension between human intuition and machine precision.

Healing Herbs and Medicine Through History

North and South America

Medical History

Indigenous nations across the Americas developed rich botanical systems long before European contact, each adapted to local ecosystems. Knowledge was empirical and spiritual: plants were seen as gifts with both physical and sacred power. After colonization, European and Native traditions blended into folk medicine and later informed modern pharmacology.

Notable Practices and People

Aztec Codex Badianus (1552): one of the earliest herbal manuscripts of the Americas.

Maya and Inca healers: used observation and ritual cleansing to restore balance.

Modern ethnobotany owes much to the documentation of Indigenous herbalists.

Characteristic Remedies

North America: Willow bark, echinacea, goldenseal, yarrow, sage, cedar smoke. Willow bark contains salicin (natural aspirin). Sage and cedar for purification and mild antisepsis.

Central America: Aloe vera, cacao, chili, agave sap, copal resin. Chili for circulation; cacao for heart health; copal burned in cleansing rituals.

South America: Cinchona bark, guarana, yerba mate, coca leaf, dragon’s blood resin (Croton lechleri) Cinchona contains quinine (anti-malaria); coca leaves as a mild stimulant; dragon’s blood aids wound healing.

Europe

Medical History

Rooted in Greek and Roman humoral medicine; later fused with monastic herbalism and Renaissance science. Medicine developed from Galen’s theory of humors to Paracelsus’s chemical model and eventually to anatomy and germ theory.

Notable Works and Figures

Hippocrates (5th c. BCE): Corpus Hippocraticum: “first do no harm.”

Galen (2nd c. CE): codified humoral theory.

Dioscorides (1st c. CE): De Materia Medica—Europe’s definitive herbal for 1,500 years.

Hildegard of Bingen (12th c.): monastic healer, integrated herbs with theology.

Paracelsus (16th c.): introduced chemical medicine.

Pasteur and Lister (19th c.): germ theory and antisepsis revolutionized care.

Characteristic Remedies

Classical: Willow, garlic, mint, thyme, opium poppy Foundations of Western pharmacology.

Medieval Monastic: Chamomile, lavender, rosemary, sage, valerian, honey. Cultivated in cloister gardens; used for digestion, sleep, and wound care.

Folk Europe: Comfrey, elderflower, foxglove, St John’s wort, yarrow. Many still used; foxglove/digitalis (heart drug).

Africa

Medical History

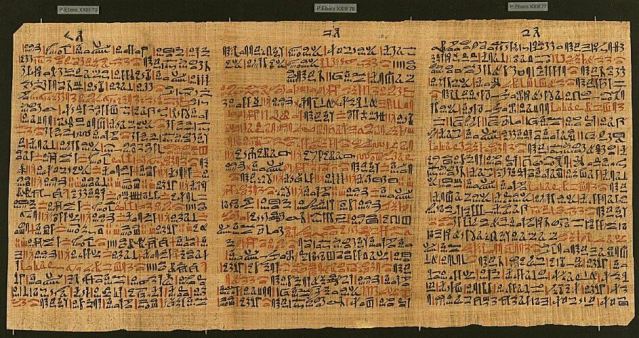

Healing intertwined with community ritual, divination, and empirical herbal knowledge. Egyptian medicine (3rd millennium BCE) left the earliest written surgical and pharmacological records. Sub-Saharan traditions emphasized holistic healing: spiritual, physical, and social balance.

Notable Works and Figures

Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE): lists 700+ remedies including honey, resin, and castor oil.

Imhotep (27th c. BCE): physician-architect later deified.

Modern ethnobotany: research in Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa continues to validate many ancient remedies.

Characteristic Remedies

Egypt / North Africa: Honey, frankincense, myrrh, castor oil, aloe vera. Antimicrobial resins and soothing oils.

West Africa: Neem, hibiscus, baobab fruit, bitter leaf, kola nut. Antimalarial and antioxidant properties.

East / South Africa: Rooibos, buchu, devil’s claw, African potato (Hypoxis). Anti-inflammatory and tonic uses; some proven pharmacologically.

Middle East

Medical History

Birthplace of Greco-Arab (Unani) medicine blending Greek, Persian, and Indian thought. Hospitals and medical schools flourished under the Abbasids; scholars preserved and expanded classical texts.

Notable Works and Figures

Avicenna (Ibn Sina, 980–1037): The Canon of Medicine, a standard text in Europe for 600 years.

Rhazes (Al-Razi): wrote on smallpox and measles; championed empirical observation.

Al-Zahrawi: surgical pioneer; developed cauterization tools.

Characteristic Remedies

Black seed (Nigella sativa): “Cure for everything but death,” mild antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory.

Dates, figs, honey, olive oil: Nutrient-dense foods as medicine.

Myrrh and frankincense: Disinfectant, wound dressing, incense for ritual purification.

Saffron, turmeric, cardamom, cinnamon: Digestive and mood-lifting properties; key in humoral balance.

Asia

Medical History

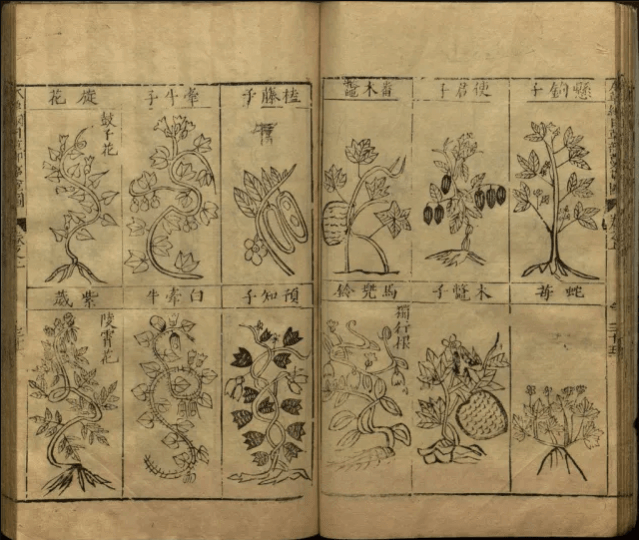

Asia developed multiple complex medical systems independently: Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), Ayurveda (India), kampo (Japan), Tibetan, Korean, and Southeast Asian blends.

All emphasize balance (yin/yang or doshas) and prevention through diet, herbs, and movement.

Notable Works and Figures

Shennong Bencao Jing (c. 200 CE, China): earliest systematic herbal.

Li Shizhen’s Bencao Gangmu (1596): 1,800 herbs classified.

Charaka Samhita and Sushruta Samhita (India): foundational Ayurvedic texts; Sushruta described surgical techniques including plastic surgery.

Characteristic Remedies

China: Ginseng, ginger, licorice root, goji berries, honeysuckle, rhubarb, mugwort (moxa). Tonics for energy, digestion, immunity.

India (Ayurveda): Turmeric, ashwagandha, holy basil (tulsi), neem, gotu kola, triphalā. Anti-inflammatory, adaptogenic, rejuvenating.

Japan / Korea: Green tea, shiitake, reishi, ginseng, shiso. Immune and metabolic support.

SE Asia: Lemongrass, galangal, tamarind, betel leaf. Digestive, antiseptic, and aromatic therapies.

Australia and New Zealand

Medical History

Aboriginal and Māori peoples cultivated deep botanical knowledge suited to extreme climates. Healing was inseparable from spirituality, illness arose from imbalance between person, land, and ancestor spirits. European colonization suppressed but did not erase these traditions.

Characteristic Remedies

Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia): Antiseptic for cuts, infections. Modern studies confirm antimicrobial oils.

Eucalyptus: Decongestant, antiseptic vapor. Now a base for cough lozenges and balms.

Kakadu plum: Extremely high vitamin C; immune support. Studied for antioxidant properties.

Manuka honey (NZ): Wound healing. Medical-grade form clinically proven antibacterial.

Emu oil: Anti-inflammatory rub. Still used for muscle and joint pain.

Modern Integration

Today Australian and New Zealand research merges traditional Aboriginal, Māori, and Western medicine, focusing on bio-active native plants and respectful collaboration with Indigenous knowledge holders.

For Writers

Choose herbs appropriate to climate and trade routes: Show how healers obtain them.

Let philosophy shape treatment: an Ayurvedic healer balances doshas, a Greek physician purges humors, an Indigenous shaman restores spiritual harmony.

Show mixtures of success and failure: realism often lies where belief outpaces science.

Use genuine substances (honey, willow, turmeric) to ground fantastical cures in believable tradition.

Depicting Healing Herbs and Natural Treatments Across Genres

Herbs, tonics, and natural remedies appear in nearly every genre: from medieval monasteries to futuristic bio-labs. But the way they’re understood, used, and valued depends entirely on the world around them. A 14th-century herbalist, a modern naturopath, and a starship botanist might all reach for the same plant but for completely different reasons.

Contemporary Fiction

Modern readers live in a world of science-based medicine but remain fascinated by holistic or “natural” care. Herbal treatments often appear alongside or in tension with modern pharmaceuticals.

How to Depict Herbs Today

Focus on integration rather than opposition: characters might use chamomile for sleep while on prescribed anxiety medication, or honey to soothe wounds alongside antibiotic cream.

Show awareness of dosage, regulation, and skepticism. Today’s readers expect realism and a distinction between proven benefits and folklore.

Herbalism can reveal personality and culture: a grandmother’s remedy connects generations, while a scientist protagonist tests traditional cures under a microscope.

Include modern preparations: capsules, teas, essential oils, or extracts rather than crude poultices.

Story Function

Reflects character values (naturalist vs. rationalist). Represents cultural identity or intergenerational wisdom. Serves as a metaphor for healing that’s emotional as well as physical.

Example: A medical student dismisses her grandmother’s traditional remedies until a honey-and-herb salve from her village outperforms a commercial antiseptic in a rural clinic.

Historical Fiction

Before germ theory, medicine was trial, error, and tradition. Herbs were the only accessible treatments, and healing was often a mixture of faith, superstition, and genuine skill.

How to Depict Herbs Historically

Use plants accurate for the region and era: monks in England grew sage and valerian; Arab physicians used black seed and saffron.

Tie remedies to the theory of humors or local belief systems: a “hot” herb to balance “cold phlegm,” or a ritual blessing before applying a poultice.

Show the risk of infection and contamination, even effective herbs were applied with unsterilized hands or reused cloth.

Characters might not know why something works, only that it does. This limited understanding can create tension between healer and patient.

Story Function

Highlights the limitations and ingenuity of the past. Reveals the character’s worldview (rational herbalist vs. superstitious villager). Provides atmosphere: jars of dried herbs, smoky apothecaries, fragrant oils, and candlelit infirmaries.

Example: A 14th-century midwife uses rosemary, yarrow, and honey to save a noblewoman’s childbed fever, earning praise until the local priest accuses her of witchcraft for meddling in “God’s will.”

Fantasy

Fantasy gives writers the freedom to blend real-world herbalism with the supernatural. Herbs may carry magical properties, spiritual resonance, or hidden costs.

How to Depict Herbs in Fantasy

Ground the magic in reality: base your fictional herbs on real ones, e.g., comfrey-inspired bonebind, willow-like painleaf, or glowing moonwort that heals but drains stamina.

Make herbal knowledge cultural and practical: a dwarven miner might use lichen for lung protection; elves might brew luminous teas to restore mana.

Use herbs as magical catalysts or stabilizers, required ingredients for healing spells or potions.

Establish rules and scarcity: not every herb grows everywhere, and improper mixing could poison rather than heal.

Story Function

Enhances world-building: flora becomes part of culture, economy, and warfare. Tests the limits of magic. Does it replace herbs or rely on them? Symbolizes harmony with nature or the loss of it.

Example: A healer’s apprentice learns that her mentor’s potent healing salve works only when mixed with her own blood, revealing the herb’s magic binds to life essence, not its leaves.

Science Fiction

Science fiction reimagines herbs through biology, chemistry, and technology. Natural compounds can become advanced pharmaceuticals, or alien flora can reshape our concept of medicine altogether.

How to Depict Herbs in Sci-Fi

Future pharmacology: herbal compounds rediscovered as sources for lab-synthesized drugs.

Genetic engineering: plants modified to grow faster, produce targeted antibiotics, or adapt to new worlds.

Alien ecosystems: vegetation that heals one species but harms another; symbiotic organisms that act as living medicine.

Cultural contrast: a frontier colony depends on herbal treatments after supply-chain collapse, rediscovering ancient remedies.

Story Function

Raises ethical questions: who owns the genetic rights to a miracle plant? Explores survival and adaptation: when high-tech fails, nature endures.

Merges spirituality and science: botanists treating alien plants as both sacred and scientific wonders.

Example: On a terraformed planet, colonists cultivate a native moss that speeds up cellular repair. Decades later, they learn the moss heals by integrating its DNA into theirs, turning them slowly into hybrids.

Plot and Character Ideas

The Last Apothecary’s Daughter

Genre: Historical Fiction (17th Century)

Plot Idea: After her father’s death, a young apothecary’s daughter continues his herbal practice in secret during England’s witch trial hysteria. When a noblewoman’s son falls ill, she must risk exposure to save him.

Character Angle: Intelligent but fearful, she struggles to separate her father’s science from her society’s superstition.

Twist(s): The physician who accused her of witchcraft to eliminate competition intentionally caused the boy’s illness.

Bitterroot Remedy

Genre: Contemporary Drama

Plot Idea: A burned-out pharmacist in Montana rediscovers her passion for healing after meeting a Native herbalist who teaches her traditional plant medicine.

Character Angle: Rational to a fault, she’s skeptical of anything not backed by lab data, but chronic pain forces her to try what science can’t explain.

Twist(s): Her pharmacy chain tries to buy and patent the herbalist’s recipes, and she must choose between career and conscience.

The Poisoner’s Apprentice

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A young healer is apprenticed to a royal herbalist whose remedies are also deadly poisons depending on dosage. When the king is poisoned, suspicion falls on her.

Character Angle: Naïve but quick-witted, she must navigate palace intrigue armed only with her master’s coded herbal journals.

Twist(s): The poison that killed the king is her own creation, altered in secret by someone she trusted.

Garden of the Moon Priestess

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: In a world where plants glow with lunar energy, a priestess who tends the sacred gardens must save her people when the moon’s light fades.

Character Angle: Her faith is shaken as every cure she brews fails until she realizes the plants’ power responds not to prayer but emotion.

Twist(s): The withering garden reflects her own grief; healing the plants requires confronting the loss she’s denied.

The Fever Tree

Genre: Historical Adventure (19th Century Africa)

Plot Idea: A British botanist searching for the legendary “fever tree” (source of quinine) partners with a local healer who already knows its secret but not the greed it will unleash.

Character Angle: Idealistic about discovery, he learns the cost of “progress” when his research threatened to exploit the very people he depends on.

Twist(s): The fever tree exists, but it’s symbiotic with a fungus that dies in captivity, dooming any attempt to mass-produce it.

The Herbalist of Ironvale

Genre: Steampunk Fantasy

Plot Idea: In a smog-choked industrial city, a self-taught herbalist treats miners poisoned by factory runoff until a powerful guild accuses her of sabotaging progress.

Character Angle: Tough and resourceful, she’s haunted by a past as a factory nurse who ignored early victims.

Twist(s): The city’s pollution is creating new, mutagenic herbs underground, plants that could both cure and kill.

Code Green

Genre: Science Fiction / Eco-Thriller

Plot Idea: On a dying Earth, a bioengineer discovers an ancient plant in the Amazon that can cleanse air toxins, but its pollen may be dangerously addictive.

Character Angle: Struggling between ecological salvation and ethical restraint, she hides her research from corporate backers hungry for control.

Twist(s): The plant is sentient and begins communicating through dreams, urging her to destroy all human industry.

The Apothecary’s Ledger

Genre: Historical Mystery (18th Century)

Plot Idea: A London apothecary’s detailed patient ledger becomes the key to solving a string of suspicious deaths among society’s elite.

Character Angle: A widowed bookseller inherits the ledger and is drawn into the web of secrets it records.

Twist(s): The apothecary was blackmailing patients with knowledge of their ailments, and the killer is one of his “cures.”

Wild Honey

Genre: Contemporary Romance / Healing Drama

Plot Idea: A war veteran with PTSD returns home to run his late grandfather’s bee farm. A local herbalist helps him rediscover purpose as they create healing salves from honey and wild herbs.

Character Angle: Quiet and guilt-ridden, he struggles to believe he deserves peace.

Twist(s): The honey from one hive contains a rare antibacterial compound that could revolutionize medicine, but selling it would destroy the land that healed him.

The Saffron Conspiracy

Genre: Political Thriller

Plot Idea: In the near future, a spice genetically engineered to cure heart disease becomes the world’s most valuable resource. A botanist-turned-smuggler tries to keep it from being monopolized by pharmaceutical giants.

Character Angle: Formerly idealistic, she’s haunted by her role in creating the monopoly she now fights against.

Twist(s): The “saffron cure” only works if grown in native soil, making the poorest farmers the key to the planet’s survival.

The Healer of Red River

Genre: Historical Western

Plot Idea: A former Civil War nurse opens a frontier clinic, using Native and folk remedies to treat settlers and Indigenous patients alike, drawing suspicion from both communities.

Character Angle: Pragmatic yet empathetic, she values results over politics, walking a moral tightrope.

Twist(s): Her secret ingredient – black willow – becomes the first formulation of aspirin, years before it’s patented.

Seeds of the Stars

Genre: Science Fiction

Plot Idea: A deep-space botanist aboard a generational ship tends a collection of ancient Earth plants. When a mysterious plague infects the crew, she discovers the cure hidden in her forgotten garden.

Character Angle: Isolated and dismissed as obsolete, she finds renewed purpose as humanity’s last healer.

Twist(s): The cure isn’t a plant, it’s a symbiotic spore that will alter human DNA forever, making them part-plant to survive alien worlds.

Healing herbs have always balanced hope and harm, bridging faith, nature, and early science. Whether your healer is a medieval apothecary, a fantasy herbalist, or a space botanist, grounding their knowledge in real principles like antiseptic honey or willow bark pain relief adds authenticity.

Remember: not every cure needs to work perfectly. Sometimes, the struggle to heal with limited tools makes a character and a story feel most human.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.