Introduction to Worldbuilding

Posted on January 5, 2024 Leave a Comment

Fantasy literature transports readers to unimaginable realms, where they can escape reality and embark on epic quests, encounter mythical creatures, and explore magical lands. The key to the magic of these stories lies in creating fantasy worlds that are immersive, believable, and awe-inspiring. These realms become characters in their own right. The art of worldbuilding that captivates and inspires readers is what we’ll explore over this year. Worldbuilding is essential for crafting immersive stories, whether you’re an aspiring writer or a fan of fantasy.

To create a believable and engaging setting, you must start with a solid foundation. Here are some key considerations when crafting your world. I will be exploring all these topics in greater depth over the next year.

Creating a Believable Setting

Begin with the basics.

Geography and Topography – What is the lay of the land? Consider the physical features—mountains, rivers, forests, deserts—that make up your world. Are there vast underground caverns, lost cities, or labyrinthine catacombs? How do these elements affect the climate, ecosystems, and the civilizations that inhabit them?

Climate and Weather – Weather plays a crucial role in setting the tone of your world. Think about seasonal changes, unusual weather patterns, and their impact on agriculture, travel, and daily life. Weather patterns and seasonal changes influence the behavior of flora and fauna. These factors also affect how your world’s civilizations have developed.

Flora and Fauna – Populate your world with a diverse range of plants and creatures. Consider their adaptations to the environment and their role in your world’s ecosystem.

History and Lore

Every fantasy world has a history filled with legendary wars, iconic heroes, and world-altering events. Create a detailed history and lore for your world.

Historical Events and Conflicts – Think about pivotal moments in your world’s past. These events can shape your cultures and inform your characters and their motivations. They can also impact the political landscape.

Races and Species

Whether your world is populated by humans, mythical creatures, or a mix of both, give careful thought to its inhabitants.

Creating Diverse Races – Do you want different races and species with unique characteristics and histories in your world? Consider how these races interact and what conflicts or alliances may arise.

Cultural Diversity

In a well-rounded fantasy world, cultures add richness and depth to your setting.

Languages and Linguistics – Develop distinct languages for different cultures, with their own scripts and dialects. Language can be a powerful tool for worldbuilding.

Religions and Belief Systems – Explore the religions in your world. Are there pantheons of gods, monotheistic faiths, or animistic beliefs? How do these religions influence daily life and morality? If there are multiple religions in your world, how do the followers of different faiths interact with each other? Are they peaceful or antagonistic?

Political Systems and Factions – The political landscape of your world can be as intricate as its cultures. Are there kingdoms, empires, or city-states? Are there power struggles, alliances, or wars on the horizon? Political intrigue can be a rich source of conflict and plot.

Cultural Traditions and Rituals – What traditions and rituals exist in the cultures of your world? Explore how geography, climate, and history have affected culture. Cultural aspects encompass literature, gender roles, social institutions like marriage and education, superstitions, and more.

Economy and Trade: The Lifeblood of Your World

Economic systems play a vital role in shaping your world’s societies and conflicts.

Economic Systems – How do people earn a living? What is the currency, and how is wealth distributed? Resources are also critical factors to consider.

Trade Routes and Commerce – Think about the trade routes that crisscross your world. How do they influence cultural exchange and the flow of goods?

Technology and Advancements – Determine the level of technology in your world. Is it a medieval society with swords and horses, or is it a technologically advanced world with steam-powered contraptions? Technology influences every aspect of life, from transportation to communication.

The Magic of Magic Systems

Magic is often a central element of fantasy worlds, and its form is a vital thread in the fabric of your setting.

Magic Rules and Limitations – Establish clear rules for how magic operates in your world. Is it bound by specific laws? Are there limits to its power? Is it something that comes naturally or do people need to be taught and practice it to become skilled? Is magic taught in formal academies, through apprenticeship, or by personal trial and error? This not only adds depth but also provides opportunities for conflict and growth.

Types of Magic Users – Define the various magic users, from wizards and sorcerers to witches and warlocks. Explore their unique abilities and how they fit into the broader society. Are magic users powerful people in the government and society or are they feared and hunted?

Cultural Influence – Consider how different cultures within your world approach and interact with magic. Is it revered, feared, or a closely guarded secret? How do these beliefs shape the world’s politics and religions?

Hidden Realms – Are there hidden realms in your world accessed through portals, magical gateways, or ancient artifacts? These can be realms of wonder, danger, or both.

The Art of Visualizing: Creating Maps and Geography

Maps and visual aids are invaluable for both writers and readers. They provide a tangible sense of your world’s geography and help orient the reader.

Sketching Maps – Create maps of your world, whether it’s a single continent or an entire cosmos. Maps help you keep track of locations and distances, ensuring consistency throughout your narrative.

Visual Aids – Consider using visual aids like sketches, diagrams, or 3D models to help readers picture key places, objects, and creatures.

Building Worlds for Different Fantasy Subgenres

Different subgenres of fantasy require unique worldbuilding approaches.

Worldbuilding for High Fantasy – Embrace the epic and the mythical. High fantasy often features sweeping landscapes, legendary artifacts, and world-altering events.

Worldbuilding for Urban Fantasy – Blend the magical with the mundane. Urban fantasy typically places fantastical elements in a contemporary urban setting.

Worldbuilding for Steampunk – Give your world a Steampunk touch by incorporating Victorian aesthetics, steam-powered machinery, and an industrial revolution atmosphere.

Characters in Your World: Integration and Impact

Characters are the lens through which readers explore your world. The world shapes their backgrounds and experiences they inhabit.

Character Integration – Ensure that you seamlessly integrated your characters into the world. The culture, politics, and history of the world they live in should influence their personal stories.

Reader Engagement – Engage your readers by immersing them in your world. Use descriptive language and character experiences to make the setting come alive.

Fantasy worldbuilding takes time, creativity, and careful consideration. Each facet of your world, from its geography and cultures to its magic systems and mythical creatures, contributes to the spectacle of your story. Remember that your goal is to transport your readers to a realm of wonder and adventure, where the boundaries of reality fade away, and the possibilities are limited only by your imagination. Happy worldbuilding!

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2024 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

The Writer’s Guide to Entering & Exiting a Harbor

Posted on December 22, 2023 Leave a Comment

Sailing ships entering and exiting harbors relied on a combination of wind power, currents, and manual labor. The techniques and procedures varied depending on the size of the ship, prevailing wind and tide conditions, and the design of the harbor. Here is a general overview of how sailing ships entered and exited harbors.

As always, magic is the exception to the rule. Because magic.

Entering Harbor

The crew of the ship would use maps, instruments (like sextants), and landmarks to find their way to the harbor.

As the ship approached the harbor entrance, the crew would reduce sail by furling or lowering some sails. This reduced the ship’s speed and made it more maneuverable.

The anchor would be ready to drop in case of emergencies or if the ship needed to come to a stop quickly.

Many times, local pilots familiar with the harbor would come on board to guide the ship safely through the narrow and often treacherous entrance. Pilots had specialized knowledge of the harbor’s currents, tides, and hazards.

Depending on the wind direction and the layout of the harbor, the crew would use various techniques to maneuver the ship. These might include tacking (changing the direction of the ship by turning it into and across the wind) or wearing ship (changing direction by turning away from the wind). In the time before motorized vessels, sailors would use row boats to pull ships into harbor. Later, they would fill this role with tugboats. Another method they used was to let out the anchor, load it onto a rowboat, and drop it further out in the direction they wished to go. They would then weigh anchor, pulling the ship towards it. Sailors commonly took advantage of the incoming tides to push their ships into the harbor.

The ship’s crew and harbor authorities would communicate using signal flags, semaphore, or other means to coordinate the ship’s entry.

Once safely inside the harbor, the ship would drop anchor and secure it to the seabed to prevent drifting. They often did this with manual capstans or windlasses. They would also secure the ship to the dock using ropes that were tied to cleats on the dock and sturdy points on the ship. Typically, sailors used three lines: a bowline, a stern line, and a spring line. These lines were tight enough to prevent the boat from drifting too far, but slack enough to allow it to move with the tide and wind.

Exiting Harbor

To leave the harbor, the ship’s crew would “weigh anchor,” which meant raising the anchor from the seabed. This required the use of capstans or windlasses powered by the crew’s muscle.

Once they had secured the anchor, the crew would set the sails. The configuration of sails depended on the wind direction and the ship’s desired course.

The ship’s crew would plan their route out of the harbor, considering the wind and tide conditions. They would aim to avoid obstacles and other vessels.

Like entering the harbor, the crew would use various sailing maneuvers to navigate through the harbor entrance. The crew had to balance the speed and direction of the ship with care to avoid collisions and ensure a safe exit. Sailors used the same methods applied to bring a ship into harbor in reverse to exit the harbor.

Sometimes, a harbor pilot might continue to guide the ship out of the harbor to ensure a safe departure.

Once the ship had safely navigated the harbor entrance, it would set its course for its intended destination, adjust its sails as necessary, and resume its journey under wind power.

These procedures required skilled seamanship, teamwork, and a deep understanding of the local conditions. Bad weather, strong currents, or crowded harbors can make entering and exiting difficult.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2023 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

Writer’s Deep Dive: Sextant

Posted on December 8, 2023 Leave a Comment

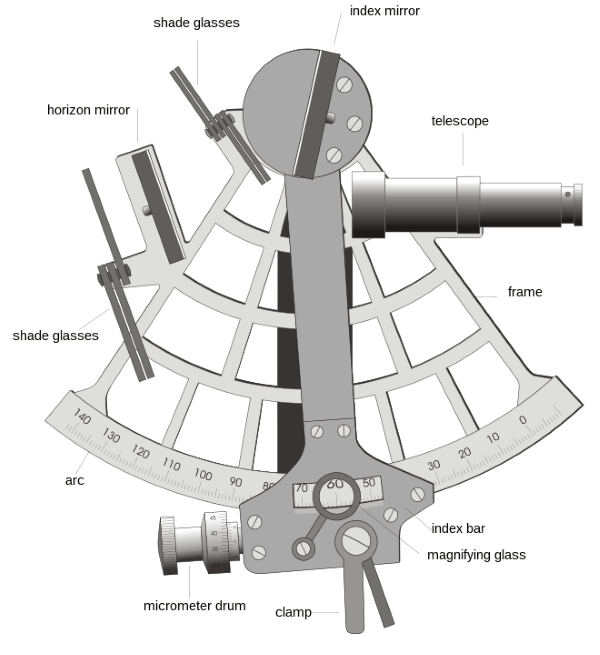

The sextant is one of the most easily recognizable and yet least understood navigational instruments. Today I will explain how to take a reading with the sextant and the function of all its pieces.

Now, let’s dive in!

The Basics

The basic principles of the sextant were found in the unpublished writings of Isaac Newton but were first implemented around 1731 by John Hadley and Thomas Godfrey.

The sextant measures the angular distance between two visible objects. Often one of those objects is the horizon, and the other is the sun or the north star. However, the sextant can also measure the distance between two objects, such as the moon and another celestial body, such as a star or planet. This can determine Greenwich mean time and thus longitude. You can calculate the latitude by noting the time of a sighting and measuring the angle. The distance of a landmark can be determined by sighting the height of it. When held horizontally, a sextant can measure angles between objects on a chart. Unlike older tools, you can use the sextant during the day or at night. Because a sextant measures relative angle, it does not need to be completely steady, meaning that you can use it on a moving ship.

The frame of a sextant is marked with angles. You move the index bar to take a reading on those angles. Traditional sextants have half horizon mirrors, so one mirror shows the horizon and the other shows the celestial body being cited. Both objects appear bright and clear, meaning that you can use the sextant at night and in haze. Most sextants have shade glasses to protect the user’s eyes from looking directly at the sun.

Sighting, shooting, or taking a sight is how people refer to taking a reading with a sextant. First, point the sextant at the horizon. Then rotate the index bar until the celestial body being cited appears in the second half of the mirror. Then, line up the bottom of the celestial object with the horizon, release the clamp, and swing the sextant side to side to verify alignment. The user can then read the angle that is shown by the arrow on the index bar.

The readings for a sextant are sometimes subject to index errors. This is due to slight misalignments with the mirrors. You can adjust calculations to ensure the accuracy of the reading. Adjustments for height above the water, light bending, and shift in position of the celestial body are usually necessary. Changes in temperature can warp the ark of the sextant, creating inaccuracies. Mariners originally made most sextants of brass because it expands less than other materials although it was heavier.

Users can determine their location on earth by using trigonometric calculations and nautical almanac data after correcting their reading.

The Write Angle

There are many ways that you can use a sextant in your stories. Below are just a few.

Navigational Tool – The sextant was an essential navigation tool in history. It was useful for people who explored uncharted territories like sailors, pilots, and explorers without GPS.

Historical Setting – If sextants were commonly used in the specific historical period in which your story is set, it can serve as a hallmark for the era and illustrate the challenges of navigation in the past.

Survival Story – If your character is in a survival situation, such as after a shipwreck, a sextant can be a lifeline for them to find their way to safety. If they struggle with using the instrument accurately, it can add a layer of tension and hope. If there is more than one survivor, they can disagree about how to use a sextant and whether each other’s readings are accurate.

Character – Showing a character that is competent at using a sextant or struggling can add depth and reveal some of their skills and back story. If your character is based on a historical figure such as a famous explorer or scientist, their use of the sextant can add depth and authenticity to your story.

Mystery – Maybe your character stumbles upon an old sextant with cryptic markings or coordinates that are the beginning of an adventure.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

May you always find the right words.

Copyright © 2023 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

The Writer’s Guide to Maritime Navigation

Posted on November 24, 2023 Leave a Comment

Over the last couple of weeks, I have covered different ships and a large span of maritime history. However, all these ships mean nothing if you do not know how to get where you are going. Today I will cover maritime navigation. I will mainly focus on navigation before satellite and radio.

As always, magic is the exception to the rule. Because magic.

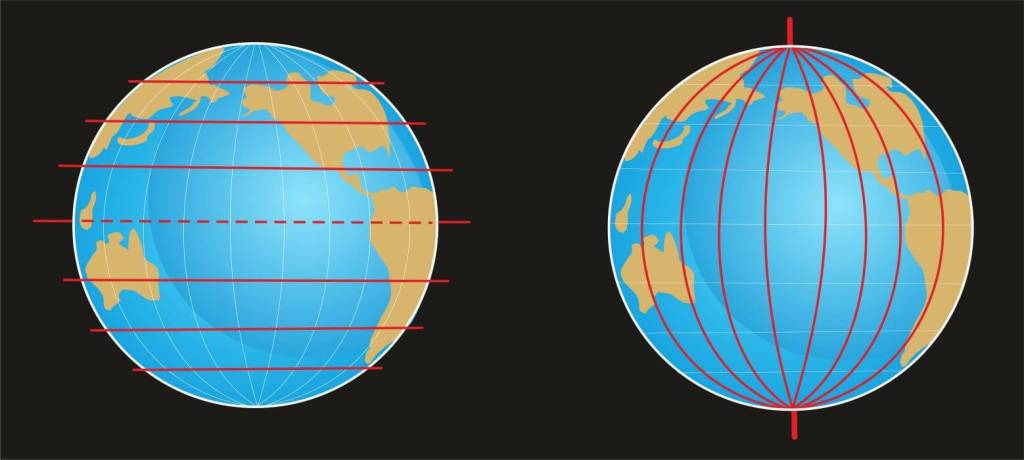

Latitude and Longitude

Latitude is the distance north to south around the globe and is depicted as horizontal lines on maps of the Earth. It is usually expressed in degrees with the equator being 0 degrees. Mariners calculated latitude in the northern hemisphere by sighting the sun, moon, or north star with a sextant.

Longitude, the vertical lines on your map, dictate east-to-west distances from the prime meridian or Greenwich meridian. Longitude is also expressed in degrees ranging from 0 to 180 degrees east to west. Longitude is much harder to calculate than latitude because you must know the exact time that you are from Greenwich mean time. This requires hyper accurate timepieces which were not available until the late 18th century and not affordable until the 19th century.

Coastal Navigation

Our earliest seafaring ancestors followed the coast. With the shoreline in sight, it was harder to get lost than venturing out into open waters.

Dead Reckoning

Early mariners navigated by using landmarks, memory, observation, and information passed down by others. A variation of this type of navigation is known as dead reckoning. A ship captain would point his vessel in the direction that he wished to go and try to hold a straight line. He would estimate his location given the speed of the ship. This is not the best navigation method because any steering error can take the vessel wildly off course.

Celestial Navigation

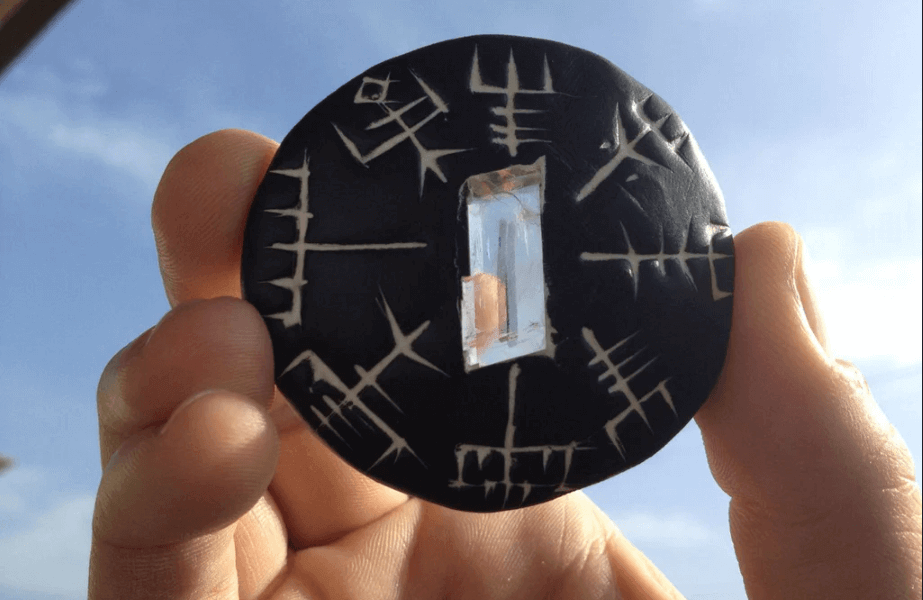

Celestial navigation is based on the observation of the sun, moon, and stars. Sailors would use the sun to set an east or west heading. The North Star was used heavily by early mariners at night. Ancient Vikings are rumored to use a special type of crystal known as a sunstone to locate the sun even on a cloudy day and then utilize a primitive compass known as a sunboard to set their heading. If you are interested in learning more there was a fantastic episode of Expedition Unknown that covers this topic.

Astrolabe

An astrolabe is an instrument that serves as a star chart and a physical model of visible heavenly bodies. It is usually a metal disc with a pattern of wire cut outs and perforations that allow the user to accurately calculate astronomical positions. It can measure the altitude above the horizon of a celestial body and can identify stars or planets to determine latitude. Although it is less reliable in rough seas. The astrolabe was used widely during the Islamic Golden Age.

Compasses

The compass uses a magnetized needle to determine magnetic north. They also show angles in degrees with N corresponding to 0 degrees. This allows the compass to show bearings in degrees. The Han Chinese developed the first compass using lodestones. [1] The earliest representation of a compass used aboard ship was from an illustration dating to 1403.

Sextant

The sextant is an instrument that measures the altitude of an object. The sextant measures the angle and time, which can calculate the latitude. I will go into further detail in my next blog post.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

May you always find the right words.

Copyright © 2023 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Lowrie, William (2007). Fundamentals of Geophysics. London: Cambridge University Press. pp. 281. ISBN 978-0-521-67596-3. Early in the Han Dynasty, between 300–200 BC, the Chinese fashioned a rudimentary compass out of lodestone ... the compass may have been used in the search for gems and the selection of sites for houses ... their directive power led to the use of compasses for navigation

Writer’s Deep Dive: Frigates

Posted on November 10, 2023 Leave a Comment

Unlike most of the other ships I have covered, the frigate was a warship first and foremost.

Now, let’s dive in!

The frigate was a full-rigged ship, built for speed and maneuverability, making it ideal for scouting, escorting, and patrolling. They could carry six months’ worth of stores, giving them a very long range. During a sea battle, commanders would station them away from the action with a clear line of sight to the flagship, repeating its signals. [1]

Throughout their history, frigates were a desirable post in the Navy. They often saw action, which meant a greater chance for glory, promotion, and prize money. Also, governments kept them in service during peacetime because they were more economical than larger ships. Frigates are popular among authors because of their relative freedom compared to ships-of-the-line. Examples include C.S. Forester’s Horatio Hornblower series and the movie Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World.

Early History

The frigate is descended from lighter galley-type warships developed in the Mediterranean in the 15th century. These ships used oars and sails and were primarily built for speed and maneuverability. [2] During the Eighty Years War, Protestant rebels from the southern Netherlands used frigates to attack the shipping of the Dutch and their allies. They chose the frigate because of its speed and maneuverability.

The Dutch Republic was the first navy to build larger ocean-going frigates. In their struggle against the Spanish, speed and a shallow draft for the waters around the Netherlands was critical. The first of these larger frigates were built around 1600 in Holland. The Dutch almost completely stopped using heavy ships and adopted lighter frigates by the end of the Eighty Years’ War. After the Battle of the Downs in 1639, frigates became the preferred choice for navies after seeing the Dutch’s success. Most of the ships built by the Commonwealth of England in the 1650s were frigates. As frigates became bigger, more decks were added. This style was known as a great frigate and could carry up to 60 guns. The long hull design led to the rise in broadside tactics and naval warfare.

The Classic Frigate

The classic or true frigate came into its own during the Napoleonic wars. During the War of Austrian Succession (1740-1748), the British Navy took some French frigates and liked them so much that they created their own. One of these was the French built Médée of 1740. The first British frigates had 28 guns, including an upper deck battery. The classic frigate was square-rigged and only had one gun deck. This design meant that even in rough seas, a true frigate could bring all her guns to bear against two deckers that often could not open their lower deck gun ports. The first British frigates had 28 guns, including an upper deck battery of 24 nine-pounder guns. Later designs had 32 or 36 guns, including an upper deck battery of 26 12-pounder guns.

The Heavy Frigate

In 1778, the British admiralty introduced a heavy frigate with a main battery of 28 18-pounder guns. The British made this move because the French and the Spanish had built up their navies. The French followed suit in 1781 with an 18-pounder frigate. By the Napoleonic Wars, the 18-pounder frigate was the standard. The British produced two versions: a 38 gun and a smaller 36 gun frigate.

The Super Heavy Frigate

In 1782, the Swedish Navy introduced the first super heavy frigates that had 24 pounder long guns. In the 1790s, the French built several super heavy frigates and modified a few older ships into heavy frigates. The British followed suit and modified three of their smaller 64 gun battleships into super heavy frigates including the HMS Indefatigable. In 1797 the new United States had three super heavy frigates including the USS Constitution. [3] After losses in the War of 1812, the Royal Navy ordered British frigates to never engage American frigates at any less than a 2 to 1 advantage. The builders constructed the Constitution and her sister ships, President and United States, using live oak which made their hulls resistant to cannon shot. [4] This is the reason the USS Constitution is known as Old Ironsides.

Modern Frigates

With the adoption of steam power in the 19th century, multiple navies experimented with paddle frigates. The first ironclads were classified as frigates because of the number of guns they carried. Starting in the mid-1840s there were screw frigates, first built of wood and later of iron that continued to perform the traditional role of the frigate into the late 19th century. The term frigate stayed in use until the 1880s, when iron hulled warships began being designated as battleships or armored cruisers. The term frigate was readopted during World War II by the British Navy to describe an anti-submarine escort vessel that was larger than a corvette but smaller than a destroyer. Modern frigates are included in multiple navies around the world, including the United States, Canada, and the UK.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

May you always find the right words.

Copyright © 2023 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17. p. 469. [2] Henderson, James: Frigates Sloops & Brigs. Pen & Sword Books, London, 2005. ISBN 1-84415-301-0. [3] USS Constitution launched in 1797.HMS Victory is the oldest commissioned (put on active duty) vessel since 1778 by 21 years, but she has been in dry dock since 1922. [4] Archibald, Roger. 1997. Six ships that shook the world. American Heritage of Invention & Technology 13, (2): 24.