The Writer’s Guide to Noble Titles

Posted on January 28, 2022 110 Comments

Today I will cover the titles and forms of address for members of the nobility. Collectively, the nobles of a country or kingdom are known as the peerage. There was a strict pecking order within the peerage during much of European history and it still exists in a form today in the United Kingdom and other European countries where the nobility is intact.

If you are interested in titles for royalty, I suggest you read my previous article, The Writer’s Guide to Royal Titles. Just as with that article, I will focus on medieval and Renaissance Europe.

Duke and Duchess

A duke was the highest-ranking member of the peerage, below only royalty. Several royal families have the traditional of giving princes the title of duke, including the UK, Belgium, Denmark, Spain, and Portugal. A duchess was the wife of a duke and could be of royal blood or not.

The proper form of address both in writing and verbally is “Your Grace,” although “My Lord Duke” can also be used. [1] “Your Grace” is used only with those of royal blood. [2] If a duke is greeting another duke in a formal setting, they would use “your Grace” if both are of royal blood or “my Lord Duke,” if they are not. In an informal setting, they would use “Duke (Name)” and if they are friends and in a private setting, they would likely use their first names.

The same rules apply for a duchess, although she would use the term “Duchess.”

A duke or duchess could also be referred to by the name of the territory they control, even if they are of royal blood. For example, Prince William and his wife, Catherine, are referred to as the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge.

Marquis and Marchioness

The rank of marquis and marchioness originated in France. It also refers to a noble who is given land on the border of a country, commonly called a march, and has a special duty to defend it against invasion. In the UK, the title is spelled marquess.

The formal form of address was “my Lord” or “your Lordship.” “Marquis (Name)” could be used in more informal settings.

A marchioness is the wife of a marquis. She would be referred to as “my Lady” or “your Ladyship” and informally as “Lady (Name).”

Just as with a duke and duchess, a marquis could be referred to by the name of the territory he controls. For example, John Stewart, the Marquis of Waterton would be called Lord Waterton but not Lord Stewart or Lord John. [3] His wife, Anne Stewart, the Marchioness of Waterton would be called Lady Waterton or Lady Anne but not Lady Stewart. A married woman was also never referred to by her maiden name.

Earl and Countess

Earl is an ancient title that likely originated from the Scandinavian title jarl and referred to a high-ranking chieftain who ruled in the king’s stead. [4] The wife of an earl is a countess.

All the same rules for a marquis and marchioness apply.

Viscount and Viscountess

Use of the title viscount and viscountess varies between different European counties. In some, it is an administrative or judicial title, while in others, such as the UK, it is a hereditary title.

All the same rules for a marquis and marchioness apply.

Baron and Baroness

Baron and baroness were titles that originated in France and were introduced to England after the Norman Conquest of 1066. They later spread to Scotland, Italy, and Scandinavia.

All the same rules for a marquis and marchioness apply.

Knight and Lady

A knight is a warrior given a title and lands by a monarch as a reward for military service. The title was commonly hereditary. [5] The wife of a knight was usually referred to as a lady. A knight could hold another higher title or not.

The common form of address was “sir” although he could also be referenced by name. For example, Sir Thomas Ward would be called Sir Thomas or Master Ward, but not Sir Ward. His wife, Margaret, would be called Lady Ward or Dame Margaret. [6]

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2022 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Montegue-Smith, Patrick, ed. (1984). Debrett's Correct Form. London: Futura Publications. p. 27. ISBN 0-7088-1500-6. [2] Secara, Maggie, A Compendium of Common Knowledge 1558-1603, Popinay Press, Los Angeles, CA, 1990-2008, ISBN 978-0-9818401-0-9, p. 25. [3] Secara, Maggie, A Compendium of Common Knowledge 1558-1603, Popinay Press, Los Angeles, CA, 1990-2008, ISBN 978-0-9818401-0-9, p. 26. [4] "Earl". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 24 March 2020. [5] Almarez, Felix D. (1999). Knight Without Armor: Carlos Eduardo Castañeda, 1896-1958. Texas A&M University Press. p. 202. ISBN 9781603447140. [6] Secara, Maggie, A Compendium of Common Knowledge 1558-1603, Popinay Press, Los Angeles, CA, 1990-2008, ISBN 978-0-9818401-0-9, p. 27-28.

Writer’s Deep Dive: Aiming a Bow

Posted on January 21, 2022 3 Comments

Bows show up a lot in books, from Robin Hood to Katniss Everdeen. Of course, one of the keys to being a good archer is hitting what you’re aiming at. Unfortunately, unless you have shot a traditional bow, most people do not know what that involves. Let’s dive in!

The Basics

There are two schools of thought when it comes to shooting a bow and they are aiming versus instinct shooting. Aiming, as the name implies, involves carefully setting up your shot to hit your target. Instinct shoot involves drawing the bow and loosing it when you feel it is in the right spot to hit the target. Really, there is no right or wrong way if you hit where you want to.

However, we are going to be covering several aiming techniques today. Before I jump in, I want to stress the importance of good form. Your fictional archer needs to be pulling the bow to full draw back to their anchor point, a spot on their face or jaw that they always go to. This repetition makes you a much more consistent shooter. This is a good video to explain anchor points.

For all the following aiming methods, it is common to close the eye further away from the arrow and aim with the other. For example, if you are a righthanded shooter, like most archers are, you will be aiming with your right eye. Although there are plenty of archers who keep both eyes open.

If you are shooting at a close to mid-range target, say 10-30 yards (9-27 m), you will line up the tip of your arrow with the spot on the target that you want to hit. This is commonly called “point on” targeting.

If you are at a further distance, you will have to use a technique known as gap shooting. Say you want to hit the bullseye of a target. You would aim at a point above it to account for the amount the arrow will drop in flight. Gap shooting is also used to adjust from left to right to account for wind. For long distance shooting, say 60 yards (55 m), the arrow must be arched. The bow is raised and often the archer overdraws past their face and anchors on their chest.

Facewalking is when an archer changes their anchor point. For example, if they have been anchoring at the corner of their mouth but change to anchor on the back corner of their jaw for a longer shot.

Stringwalking is used by modern recurve shooters to change the trajectory of their shots. It’s rarely utilized by traditional archers because it’s hard on wooden bows. The archer changes the position of their fingers on the string to change their shot.

There is another method that I have not been able to find a name for. A bowstring with two colors is needed and the archer counts the number of twists, moving the arrow nock accordingly.

Whatever method your fictional archer uses, they will likely have to take several shots to dial in the distance, adjusting with each try.

The Write Angle

Writing about a character carefully lining up a shot can add drama and tension to your story. This is especially true if there are obstacles or difficult weather conditions. Now that you are familiar with the various aiming methods, you can describe your character choosing a technique based on the distance and wind conditions. Being able to describe your character’s aiming adds a level of realism to your novel.

The aiming technique also changes how an arrow will hit. If your archer is “point on,” the arrow will strike at a 90° angle. However, if the shot was arched to cover a longer distance, the arrow will be striking from above at terminal velocity.

It would be interesting to see a fictional archer use facewalking to achieve a particular shot. Or to use gap shooting and describe how they are aiming for a point above their target because of the distance or to one side to account for wind.

It would also be interesting to have your archer miss the first couple of shots and adjust to dial into the target.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2022 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

The Writer’s Guide to Royal Titles

Posted on January 14, 2022 7 Comments

Fantasy writers have a love affair with royalty, with kings, queens, and princes littered across the genre. Yet royals and nobles appear in other genres as well, such as science fiction. But unless you interact with a real royal court or a group playing one at your local Renaissance faire or SCA event, most writers struggle. This is especially true if your protagonist is a member of a royal family.

Today I will be covering titles and forms of address in a variety of situations. I will be pulling mostly from medieval and Renaissance European traditions. The rules change dramatically between countries and time periods and vary due to situations and personal preference If you are writing fantasy, they can be discarded completely in favor of your own inventions, if you so wish.

Situations and Personal Preference

The forms of address varied based on the situation and personal preference. For example, if a king was a pompous ass, he could demand his subjects and staff refer to him in the most formal manner all the time. A more laidback royal could request people to use her informal title or even her first name.

The forms of address would vary based on the situation. A formal audience would require different forms of address than a private meeting between people who grew up together or have a close personal relationship.

King

At the top of the great chain of being was the king. He ruled a country or kingdom, and no one was above him except God or maybe a pope.

The proper term of address both verbally and in writing is “Your Majesty” or “Your Grace.” After the initial greeting, he can be referred to less formally. During the Middle Ages, he would be called “sire” or “my king.” The modern equivalent is “sir.”

If a king is greeting another king in a formal setting, he would likely refer to him as “Your Majesty.” If he was being especially formal or buttering him up, he could refer to him as “Your Most Royal Majesty” and possibly continue with “king of (kingdom).” A king could also be called by the name of his kingdom. For example, the king of England could be asked “Will England send aid?”

In an informal setting, two kings would likely call each other “King (First Name).”

If they are close friends and in private, they would likely call each other by their first names. Unless they grew up together, the relationship would start out formal, gradually become more casual until one or both requested that the other call them by their first name.

Queen

The queen was commonly the wife of the king although she could also be a monarch in her own right.

The proper term of address verbally and in writing is “Your Majesty,” although the spouse of a king could also be referred to as “Your Highness” or “Your Grace.” After the initial greeting, she can be referred to as “madam” or “my queen.” If the queen is accompanying her husband, they can be collectively referred to as “Your Majesties.” If someone was being subtly disrespectful, they could refer to a queen ruling as a monarch as “Your Highness,” implying that she is not on the same level as a king.

A queen greeting a king or another queen ruling in her own right in a formal setting would likely use the term “Your Majesty.” A queen who is the spouse of a king would greet another spouse of a king as “Your Highness.”

In an informal setting, the same rules that apply to kings would be used here. The same for close friends in private.

Other Members of the Royal Family

Other members of the royal family include the sons and daughters of the monarch, their spouses, and their children.

The term of address verbally and in writing is “Your Royal Highness” or “Your Highness.” After the initial greeting, they can be referred to as “sir” or “madam.” Princes could also be called “my prince” or “my lord” and princesses as “my lady.”

A prince or princess greeting another prince or princess would likely refer to them as “Your Highness.”

In an informal setting, they would refer to them as “Prince (Name)” or “Princess (Name),” for example, “Greetings, Prince Derek.”

In private, two friends would use their first names.

Children were expected to refer to their parents formally, such as “my lord father” and “my lady mother.” They could also use “sir” or “madam.”

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2022 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Secara, Maggie, A Compendium of Common Knowledge 1558-1603, Popinay Press, Los Angeles, CA, 1990-2008, ISBN 978-0-9818401-0-9, p. 24-29. [2] Mortimer, Ian, The Time Traveler’s Guide to Medieval England: A Handbook for Visitors to the Fourteenth Century, Touchstone, New York, 2008, ISBN 978-1-4391-1289-2, p. 40-43. [3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forms_of_address_in_the_United_Kingdom

Writer’s Deep Dive: 18th Century Pockets

Posted on January 7, 2022 26 Comments

For the past 17 months I have been putting out Writer’s Guides in an attempt to provide writers with accurate information. However, I have received several requests to do a deeper dive into my topics. Starting this year, I will be putting out Writer’s Deep Dives every other week. However, I will continue to put out my Writer’s Guides twice a month and alternate between the two. If there is a topic that you want me to do a Deep Dive into, please reach out and let me know.

The presence and/or size of women’s pockets has been a topic of hot debate for a while. The last time women had pockets of decent size was the 18th century. Let’s dive in!

The Basics

Women’s pockets during the 18th century were a separate garment and not integral to their clothing. They tied with a ribbon around the waist and were accessed by slits in the sides of her skirts. There could be a single pocket bag or a pair of them.

They were large! I made a pair of 18th century-style pockets for my 1775 dress based on surviving examples. They are easily large enough to fit a modern smart phone plus my wallet, fan, mitts, and car keys. There are even larger examples out there. I like to call them the mom purse of 18th century pockets.

Pockets could be plain or made of fancy fabric. Quilted or pieced pockets were popular. I have a friend who used velvet as the lining for her pocket so she could also be certain when she was inside them.

Since pockets were worn every day and were hidden from view close to the body, they were a very personal item. Many women embroidered them with private designs, sometimes including the initials of lovers. Several reenactors have kept up this tradition and there are some hilarious designs out there. Here are two of my favorites.

The Write Angle

Since 18th century pockets are so big, there are some great opportunities as a writer to take advantage of them. Several items could be smuggled inside them, including maps, bottles of poison, or a knife. Since they were rarely suspected, a woman could smuggle all kinds of things in her large pockets.

One of the risks to this design was that the ribbon that secured the pocket(s) around the waist could break. In fact, there is an 18th century nursery rhyme about that. “Lucy Locket lost her pocket. Kitty Fisher found it. Not a penny was there in it, only a ribbon round it.” Loosing a pocket could be a fantastic way to start or advance the plot in a novel, especially if the pocket contains important documents or another vital item.

Also, if a woman had embroidered the name or initials of her secret or forbidden lover on her pockets, and they were discovered by her family or husband, this could be another great way to advance the plot. Personal embroidery of this type was common during the 18th century.

It can be easy to miss the pocket opening. My first time wearing pockets, I thought I had my hand inside it and let go of my phone, only to have it fall out the bottom of my skirt. A woman missing her pocket and dropping an important item out through her skirts could also be a great plot point.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2022 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

Book Update

Posted on December 29, 2021 1 Comment

I am excited to announce that the third and final round of self editing on my up-coming novel is complete! I have already sent the first two chapters to my beta readers and after the New Year will begin the search for a professional editor.

Please stay tuned for more updates!

The Writer’s Guide to Castle Myths

Posted on December 17, 2021 6 Comments

Over the last five weeks, I’ve been providing information to give you a basic understanding of castles. Today, we are tackling the most common myths. Since castles are popular, they are depicted a lot in movies, TV shows, video games, and books. But there are several things that are often shown incorrectly.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Cold and Drafty

Castles are commonly depicted as being cold, drafty, and dark. This is often blamed on the fact they are constructed of cold stone with small windows. However, as I’ve already explained in my previous articles, castles weren’t always made of stone; many were made from timber or brick. For the sake of argument, I’m going to focus on stone castles.

In cold climates, stone can be cooling since it responds to the ambient air temperature. During the second half of the Middle Ages, the world experienced the Little Ice Age. The average temperatures dropped, and the ice pack grew. Most scientists agree that it extended from the 16th to the 19th century although others argue that it lasted from 1300 to 1850. [1] [2]

There were several ways, however, to ward off the chill in a stone castle. Thick tapestries of wool were hung on the walls to provide insulation. Rushes were used on the floors, although we don’t know if they were strewn loose or woven into mats. Canopies and curtains on beds helped to keep in the heat. Many rooms were kept small to hold in heat. Early castles had a large open hearth in the great hall and braziers in the other rooms. With the introduction of chimneys in the 12th century, fireplaces began replacing open hearths and braziers, becoming common by the 16th century. [3] [4] The people living in castles also dressed in layers to ward off the cold.

Photo source.

Grey and Colorless

When we look at existing castles today, they are grey and colorless. But they didn’t start off that way. As I covered in my previous article, there is good evidence that the exteriors of castles were covered by a layer of white plaster.

The interiors were not neglected either. Our medieval ancestors loved color. Walls that weren’t covered with insulating tapestries were often rendered with plaster and painted, as were ceilings. [5]

Use of Space

A lot of video games, especially, show castles with large rooms. Usually, there is due more to the game giving the player room to maneuver than to actual castle architecture. Excluding the Great Hall, most of the rooms in a castle were quite small. This was done to limit the waste of space and as I mentioned before, to keep rooms warm.

Stone Ceilings and Other Overuse of Stone

Another mistake that a lot of video games make, is showing that everything in a castle is made of stone. Floors and roofs were commonly made of timber beams and planks. It would be hard to make a floor out of stone (unless it was the ground floor) because the weight would require a tremendous amount of support. The exterior walls of a tower would be made of stone, but the internal floors would be timber. Ceilings or the tops of towers could be made of stone, but it would have to be buttressed to support the weight. Staircases could be made of stone or timber.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2021 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Mann, Michael (2003). "Little Ice Age" (PDF). In Michael C MacCracken; John S Perry (eds.). Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change, Volume 1, The Earth System: Physical and Chemical Dimensions of Global Environmental Change. John Wiley & Sons. Retrieved 17 November 2012. [2] Grove, J.M., Little Ice Ages: Ancient and Modern, Routledge, London (2 volumes) 2004. [3] James Burke, Connections (Little, Brown and Co.) 1978/1995, ISBN 0-316-11672-6, p. 159 [4] Sparrow, Walter Shaw. The English house: how to judge its periods and styles. London: Eveleigh Nash, 1908. 85-86. [5] https://www.quora.com/If-medieval-castles-were-whitewashed-especially-on-the-inside-what-designs-would-you-find-painted-on-the-walls

The Writer’s Guide to Siege Engines

Posted on December 10, 2021 7 Comments

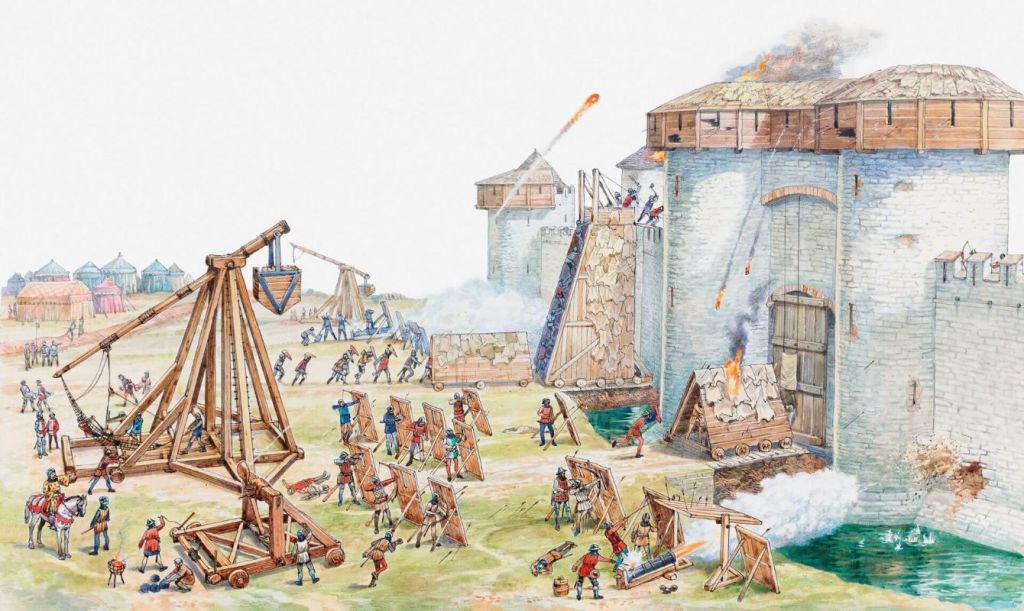

Besieging a castle or a city inherently has a great amount of built-in tension that a writer can use to fantastic effect. If you want to read besieging a castle, I recommend my last article, The Writer’s Guide to Besieging a Castle. Today, we are focusing on siege engines, a general term that includes catapults, trebuchets, and battering rams. My focus will be medieval Europe since I have limited knowledge of siege engines outside of this location and period.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Siege Tower

The earliest type of siege engine is the siege tower, also known as a belfry. [1] This might seem strange at first because it is a passive piece of equipment. However, siege towers were highly effective against walls and other fortifications. They were enclosed towers on wheels that were maneuvered into place against a wall. Then a gangplank was lowered, bridging the way to the top of the wall, and allowing soldiers to rush across. They could also have archers on the top. The benefit of siege towers was that it protected the soldiers inside from arrows and other projectiles and were sometimes covered in fresh animal hides to prevent it from being set on fire. [1] It allowed many of them to gain the battlements at one time.

The oldest siege towers were used in the 9th century by the Neo-Assyrian Empire. The Romans used them to great effect, such as at the siege of Masada in 73-74 CE. [2] The Greeks and ancient Chinese also used them.

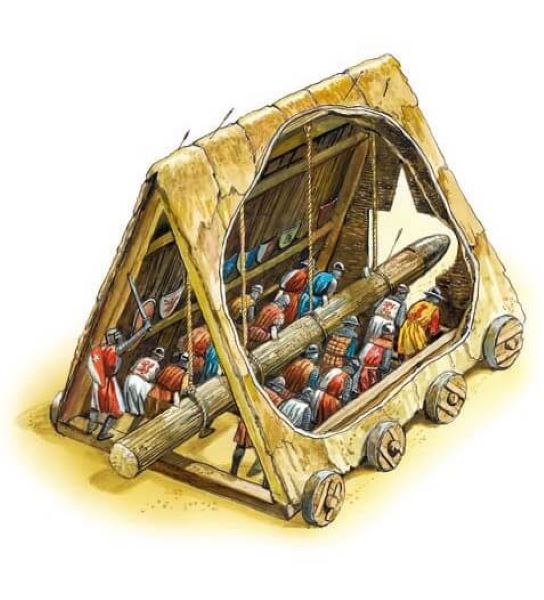

Battering Ram

The battering ram is well known in history and fiction. It comes in several forms, the simplest being a large tree trunk or log cleaned of branches that is carried by a group of people and slammed against a gate or other barrier (think “Beauty and Beast”). Later, the battering ram would be suspended from a wheeled frame by ropes or chains. It would be pulled back then allowed to swing forward. Eventually, a roof was added to the frame to protect the wielders from arrows, rocks, or whatever other nasty surprises a besieged fortress could muster.

There is some evidence that battering rams date back to Bronze Age Egypt. [3] Many cultures used them throughout history including the Carthaginians, Assyrians, ancient Greeks including Alexander the Great, the Romans, and most countries in Europe during the Middle Ages.

Photo source.

Photo source.

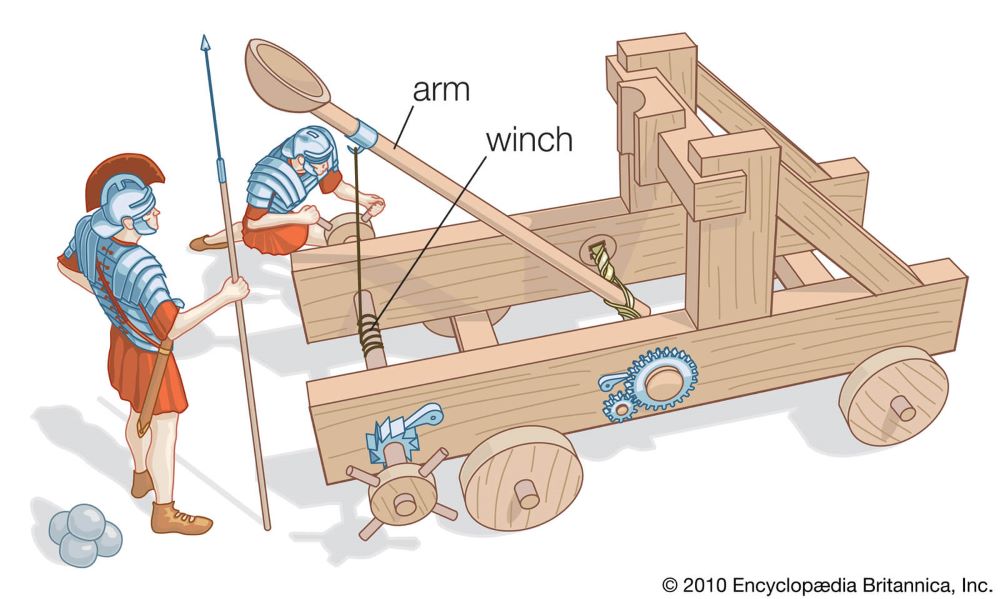

Catapult

The catapult is the first missile thrower on our list. It consists of an arm ending in a bucket, into which the missile is placed. A bundle of twisted ropes, sinew or other materials was at the base of the arm. As the arm was pulled back, it twisted this bundle further, leading to a build up of torque and energy since the twisted ropes were trying to straighten. When the arm is released, the ropes fling it forward at speed, propelling the missile in the bucket. However, this type of torsion system can only produce a certain amount of throwing power. It wasn’t enough to be effective against stone walls and was mainly used against personnel.

The earliest catapults are from 4th century China, but they were also used by the ancient Greeks and Romans. [4]

Ballista

The ballista is basically a giant crossbow and operates on the same principle. Tension is created by pulling back on the string, usually with a winch and rachet system, and flexing the bow arms. When the string is released, the missile is propelled forward. Usually, either giant crossbow bolts or stones were used. As a result of the bigger size, everything about a ballista was scaled up from its smaller cousin. Generally, it was used as an anti-personnel weapon.

The earliest ballistae were developed by the ancient Greeks although the Romans used it as inspiration for the smaller scorpion.

Trebuchet

The trebuchet was the pinnacle of siege engine technology and could dish out an incredible amount of energy and destruction. It wouldn’t be until the advent of artillery that it’s destructive power would be surpassed. The trebuchet has a long throwing arm with a sling attached to it. The throwing power was achieved either with a counterweight or traction. A counterweight trebuchet has a large bucket on the opposite end of the throwing arm that is weighed down, commonly with rocks. The arm was pulled down, either with brute form or a winch. When it was released, the counterweight dropped, swinging the arm, and attached sling up. The traction trebuchet relied on a large group of people hauling together on ropes to provide the energy to swing the arm. Please be aware that “counterweight trebuchet” and “traction trebuchet” are modern terms and we have no evidence they were used in history. [5]

Trebuchets were also incredibly versatile, and we have records of them being used to attack and defend fortifications as well as on ships. It was the first siege engine that could successfully take down castle walls. They could also fire a variety of missiles including stones or even bombs of lime and sulfur such as were fired during the Battle of Caishi in 1161. [6]

The traction trebuchet is thought to have originated in China as early as the 4th century. [7] However, it’s believed that the biggest trebuchet in history was Warwolf, which was built on the order of King Edward I of England to fight the Scots. It could reportedly throw rocks weighing up to 298 pounds (135 kg) a distance of 660 feet (200 m). [8]

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2021 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Castle: Stephen Biesty's Cross-Sections. Dorling Kindersley Pub (T); 1st American edition (September 1994). Siege towers were invented in 300 BC. ISBN 978-1-56458-467-0. [2] Duncan B. Campbell, "Capturing a desert fortress: Flavius Silva and the siege of Masada", Ancient Warfare Vol. IV, no. 2 (Spring 2010), pp. 28–35. The dating is explained on pp. 29 and 32. [3] "Siege warfare in ancient Egypt". Tour Egypt. Retrieved 23 May 2020. ...we find a pair of Middle Kingdom soldiers advancing towards a fortress under the protection of a mobile roofed structure. They carry a long pole that was perhaps an early battering ram. [4] Chevedden, Paul E.; et al. (July 1995). "The Trebuchet". Scientific American: 66–71. Original version. [5] Purton, Peter (2009), A History of the Early Medieval Siege c.450-1200, The Boydell Press [6] Needham, Joseph (1987). Science and Civilisation in China: Military technology: The Gunpowder Epic, Volume 5, Part 7. Cambridge University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3. [7] Chevedden, Paul E.; et al. (July 1995). "The Trebuchet". Scientific American: 66–71. Original version. [8] "The largest trebuchet ever built: Warwolf in the Siege of Stirling Castle / thefactsource.com". Retrieved 2020-03-25.

The Writer’s Guide to Besieging a Castle

Posted on December 3, 2021 51 Comments

Even though castles could be easily avoided by an invading force, it was often a bad idea. Attacks could be launched from them, with the soldiers retreating to their safety. During much of medieval Europe, if you wanted to take territory you had to deal with the castle of its king or lord. This usually involved a siege. Sieges are popular in books, movies, TV shows, and video games since they are full of drama and tension. Examples include the sieges of Winterfell and King’s Landing in “Game of Thrones,” the siege of Adamant in the game Dragon Age: Inquisition and the siege of Silasta in Sam Hawke’s “City of Lies.”

Today I will be covering the tactics used during a siege. Next week’s article will cover siege engines.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Fire

Since early castles were made of wood, setting fire to them was an effective means of neutralizing them. Unfortunately, we don’t have a lot of documentation of this method. The most prominent example is a section of the Bayeaux Tapestry in which two men with torches are attempting to set fire to Chateau de Dinan. [1] However, from the artwork of the period, it appears that most timber castles were not bare wood but had a layer of plaster applied to them.

Assault

The most direct route of taking a castle was to assault the gates and/or walls. This is where siege engines were used. Some, such as the siege tower, were designed to get soldiers onto the tops of the walls. From there, they could fight down to the gates and open them for the rest of the army. Others, such as battering rams, catapults, and trebuchets were designed to go through a castle’s defenses.

A direct assault was usually the quickest way of taking a castle or for that matter, a fortified city or town. [3] But it was also the riskiest and the most likely to result in high casualties. Because of the defensive features of castles, a small garrison could hold out for a long time. For example, in 1403, thirty-seven archers defended Caernarfon Castle against two assaults by allies of Owain Glyndŵr. [2]

Sapping or Mining

Sapping involved tunneling under the walls. People who performed these tasks were known as sappers. Either the miners would tunnel under the walls completely, coming up instead them, or they would collapse the walls. To do that, a void would be dug underneath them, stabilized by props and/or beams. Once complete, the beams would be removed, collapsing the void and the walls above it. [5] The easiest way to remove the supports was to set a fire in the void. There were some accounts that pigs were also trapped in the void before it was set on fire. It was thought that the pig fat helped the fire to burn hotter and faster.

If the defenders realized a tunnel was being dug, they could dig one of their own and try to intercept the sappers. Sapping was so feared that some castles surrendered as soon as they learned the sappers were at work, such as the castle of Margat in 1285. [6]

Once gunpowder became available, explosive charges were used to collapse the walls and gates. One example is the Siege of Godesberg in 1583. [4] A literary example is the battle of Helm’s Deep in “The Two Towers.”

Writer’s Tip: Sappers are rarely used in novels. I would love to see a siege in a book that was ended using sappers.

Starving Out

The safest way to take a castle or fortified city or town, was to cut them off from being resupplied and starve them out. However, this was the most time-consuming method. There are accounts of besieged castles lasting weeks, months, and in a few cases, years, if they were well supplied. Some besieging armies tried to speed up the process by using siege engines to fling corpses over the walls, hoping they would spread disease.

The danger to the besieging force was that they were stuck in one place for an extended length of time, leaving them vulnerable to attack by another enemy force.

Betrayal

Betrayal rarely makes the list of besieging methods, but it ended several sieges during the Middle Ages. A person inside the castle would open the gates to the attackers. They could either be someone who had been convinced to betray the castle or a member of the enemy force that infiltrated it.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2021 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Allen Brown, Reginald (1976) [1954]. Allen Brown's English Castles. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-069-8. [2] Friar, Stephen (2003). The Sutton Companion to Castles. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-3994-2. [3] Friar, Stephen (2003). The Sutton Companion to Castles. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-3994-2. [4] (in German) Ernst Weyden. Godesberg, das Siebengebirge, und ihre Umgebung. Bonn: T. Habicht Verlag, 1864, p. 43. [5] Friar, Stephen (2003). The Sutton Companion to Castles. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-3994-2. [6] Allen Brown, Reginald (1976) [1954]. Allen Brown's English Castles. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-069-8.

The Writer’s Guide to Castle Construction

Posted on November 19, 2021 2 Comments

If you’ve read my previous posts, The Writer’s Guide to Castles and The Writer’s Guide to Castle Defenses, you have probably realized that there were many types of castles throughout European history. As a result, the cost and time involved in castle construction varied widely.

If you are planning to have a castle under construction in your novel, I recommend you first decide on the type of castle, the location, and the budget of the builder.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Materials

Wood and earth were the cheapest materials for building castles. They were also plentiful and easy to transport. Most people did not need specialized training to work with them, meaning that a lord could call up his unskilled vassals and serfs to build his castle.

Stone was more expensive and harder to transport. It was also not as available as timber and earth. The blocks had to be cut out from a quarry then moved to the site. Some castles, such as Chinon, Château de Coucy, and Château Gaillard were constructed from stone quarried on the site. [1]

As a result of the high cost and difficulty of using stone, many castles throughout medieval Europe were made of a hybrid of the two. [2] It was also common for a country to have a mixture of timber, stone, and hybrid castles.

Another building material that is often forgotten is brick. [3] A brick castle is almost as strong as a stone one and there are castles that appeared to have been deliberately made of brick even when stone was available, such as Tattershall Castle in Lincolnshire, England.

It appears that both timber and stone (and possibly brick) castles were coated with a layer of plaster. This coating would protect them from the weather and make it difficult for attackers to know what they are up against. If you want to learn more, I recommend this video by Shadiversity.

Cost

Most of the surviving records of the cost of building castles are for royal castles, which were quite a bit more expensive than a country lord’s castle. [4] However, we do have some figures. For example, a small tower at Peveril Castle in Derbyshire, England would have cost around $137 USD. Château Gaillard in France, which was built between 1196 and 1198, cost between $20,600 and $27,500 USD. Much of the money went to paying for labor, especially skilled craftsmen, and materials. Master James of Saint George, who oversaw the construction of Beaumaris in Wales, explained it this way:

“In case you should wonder where so much money could go in a week, we would have you know that we have needed – and shall continue to need 400 masons, both cutters and layers, together with 2,000 less-skilled workmen, 100 carts, 60 wagons, and 30 boats bringing stone and sea coal; 200 quarrymen; 30 smiths; and carpenters for putting in the joists and floor boards and other necessary jobs. All this takes no account of the garrison … nor of purchases of material. Of which there will have to be a great quantity … The men’s pay has been and still is very much in arrears, and we are having the greatest difficulty in keeping them because they have simply nothing to live on.” [5]

Time

The early castles could be constructed in a relatively short amount of time. It’s estimated an average-sized motte would have taken fifty people about 40 days to construct. However, it was common for stone castles to take a decade or more to complete. For example, Tattershall Castle took 20 years (1430 and 1450) and Beaumaris Castle was constructed between 1295 and 1330, 35 years. [6]

Construction Techniques

Timber and earth castles required only simple tools and techniques to build. However, more advanced techniques were needed as castles became more complex and stones was increasingly used. Scaffolding was employed and improved from it’s use by the Greeks and Romans. [7] The treadwheel crane was vital for raising and lowering large loads. I recommend this video of a reproduction treadwheel crane lifting a car.

Upkeep

Castles were not only expensive to build but also to maintain. Since the timber used in their construction was unseasoned, it often needed to be replaced. To give you an idea of the cost, Exeter and Gloucester Castles recorded repair cost of $27 and $68 USD annually in the 12th century. [8]

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2021 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Erlande-Brandenburg, Alain (1995). The Cathedral Builders of the Middle Ages. Découvertes Gallimard ("New Horizons") series. London, UK: Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-500-30052-7.

[2] Higham, Robert; Barker, Philip (1992). Timber Castles. London, UK: B.T. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-2189-4.

[3] Cathcart King, David James (1988). The Castle in England and Wales: An interpretative history. London, UK: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-918400-08-2.

[4] McNeill, Tom (1992). English Heritage Book of Castles. London, UK: English Heritage [via] B.T. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-7025-9.

[5] McNeill, Tom (1992). English Heritage Book of Castles. London, UK: English Heritage [via] B.T. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-7025-9.

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beaumaris_Castle

[7] Erlande-Brandenburg, Alain (1995). The Cathedral Builders of the Middle Ages. Découvertes Gallimard ("New Horizons") series. London, UK: Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-500-30052-7.

[8] McNeill, Tom (1992). English Heritage Book of Castles. London, UK: English Heritage [via] B.T. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-7025-9.