The Writer’s Guide to Bows: Part 3

Posted on October 30, 2020 1 Comment

Poundage, Range, Rate of Fire & Training

In the third part of my five-part series on bows, I will be covering some more bits of critical information if you are writing an archer, especially if you’re doing a battle scene.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Poundage

Probably one of the biggest differences between historical bows and modern bows is poundage. By poundage, I mean the amount of weight the bow is exerting on the string when it is at full draw. The standard modern draw length is 28 inches (71 cm).

The draw weights of most modern longbows and recurves are in the 25-60 pound (11-27 kg) range. In 1971, the wreck of King Henry VIII of England’s flag ship, the Mary Rose, was discovered. The ship sank during the battle of Solent on July 19th, 1545. In the hold were 170 English longbows, almost 4,000 arrows and various other archery artifacts. The draw weights ranged from 100-185 pounds (45-84 kg)! [1] It took a lot of strength to pull one of these bows. Another indicator of the immense weight of medieval bows are the deformities seen in the skeletons of longbow archers from the period. They have enlarged left arms and most have osteophytes (bony projections along the joint margins) on the left wrist and shoulder and right fingers. [2]

Writer’s Tip: It would be wonderful to see a depiction of a real war bow. Unfortunately, books, movies and television tend to portray the bow as a weak person’s weapon.

Range

King Henry VIII set a minimum practice range for adults in 1542 of 220 yards (201 m). The longest recorded longbow shot was 345 yards (315 m) in the 16th century at Finsbury Fields in London. In 2012, Joe Gibbs, a well-known English longbowman, shot a 2.25-ounce (64 g) livery arrow 292 yards (267 m) using a yew bow with a 170 pound (77 kg) draw weight. [3] If you want to see Joe Gibbs in action with his 160-pound longbow, I suggest this video from Tod’s Workshop.

Rate of Fire

I can say from experience that a competent longbow archer can shoot at a rate of up to twelve arrows per minute with relatively good accuracy. The heavier the poundage of the bow, the less that rate is sustainable, however. An author in Tudor England expected a longbowman to be able to fire eight shots in the same amount of time a musket shot five. [4] However, the rate of fire could also be limited by the number of arrows available. It would not do to run out of arrows before the end of a battle!

Training

The English archers became renowned for their skills, due in large part to compulsory practice. A law passed in 1252 required all Englishmen aged 15 to 60 to own a bow and arrows. Another law passed in 1363 required them to practice archery for two hours every Sunday. [5] This law is still on the books so if you are a man living in England over the age of 14 legally you should be at the archery range every Sunday.

Despite the simplicity of shooting a bow, it takes time and consistent practice to become good. Being proficient at archery was also patriotic because it meant a man could help defend the kingdom if it went to war not to mention being able to supplement your diet with fresh game.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2020 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] https://archeryhistorian.com/the-mary-rose-longbows/ [2] Dr. A.J. Stirland. Raising the Dead: the Skeleton Crew of Henry VIII's Great Ship the Mary Rose. (Chichester 2002) As cited in Strickland & Hardy 2005, p. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_longbow [3] Loades 2013, p. 65. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_longbow#Range [4] A right exelent and pleasaunt dialogue, betwene Mercury and an English souldier contayning his supplication to Mars: bevvtified with sundry worthy histories, rare inuentions, and politike deuises. wrytten by B. Rich: gen. 1574. Published 1574 by J. Day. These bookes are to be sold [by H. Disle] at the corner shop, at the South west doore of Paules church in London. https://bowvsmusket.com/2015/07/14/barnabe-rich-a-right-exelent-and-pleasaunt-dialouge-1574/ accessed 21 April 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_longbow#Shooting_rate [5] http://www.lordsandladies.org/the-butts.htm

The Writer’s Guide to Bows: Part 2

Posted on October 23, 2020 1 Comment

Stringing & Shooting

Today is my second part in my five-part series on bows. I will be covering more of the basics of shooting so that you are better equipped to write about them in your fiction.

If you have the chance, I highly encourage you to try archery out for yourself. Experience is really the best teacher and there will be a lot of first-hand detail that you can pour into your writing. If you are specifically looking for information to write medievalesque fantasy or historical fiction, I suggest you stay away from modern compound bows. The experience of shooting one is substantially different from shooting a traditional longbow or recurve.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Stringing a Bow

Before you can shoot a bow, it must be strung. Bows should always be unstrung when not in use. If they are left strung, they will lose their power as the wood permanently takes on the bend. The power of the bow comes from a bent bow trying to be straight or mostly straight.

There are a couple ways of stringing a bow. One is putting one tip against the inside of your foot and pulling up while you slide the string into the notch with your other hand. Another method is to step through the bow, bending one limb forward while you slide the string up with your other hand. There are modern bow-stringers but I have yet to see evidence of anything like them being used in history.

How to Shoot a Bow

Most archers are righthanded so the following description is for righthanded shooting. Shooting lefthanded is simply the reverse of this description.

Before shooting, it’s important to make sure none of your clothing will interfere with drawing or releasing the string. Loose, long, or billowy sleeves can get caught up in the string as you’re firing, dissipating all the energy of the shot and causing the arrow to not leave the string or not go far. Sleeves were usually tucked or tied back unless they were slim and fitted. It was common to use an archer’s glove that covers your forearm, protecting from the string if it hits. Finger tabs or gloves were also frequently worn on the right hand to protect the fingers from the abrasion of pulling back and releasing the string repeatedly.

To start, hold the bow by the grip with your left hand, letting it cradle firmly into the webbing between your thumb and index finger. You don’t want to grip the bow but hold it lightly. If the bow has an arrow shelf make sure there is a bit of distance between it and your hand or the feathers on the arrow could slice your hand as its being shot. If the bow does not have a shelf and you’re shooting off your hand, it’s usually a good idea to wear a glove.

Next the arrow is put onto the bow or nocked. The arrow is always on the inside of the bow. The easiest way I’ve found to do this is by canting the bow slightly to the right, gripping the arrow by the end or nock, resting the front part of the arrow against the arrow rest, pulling back the end and nocking it to the string. Modern plastic nocks will snap on to the string, preventing the arrow from coming off. Traditional arrows had a small groove cut in the end of the arrow that would fit over the string but not necessary “snap” on, meaning the archer would usually have to grip it between their fingers. If the bowstring has a bead, the arrow is nocked right below it.

Most arrows have three feathers or fletching. One is usually a different color from the others and is known as the index or cock feather. When nocking, you want to make sure the index feather is facing you. If it’s facing the opposite direction, it will drag against the bow when the arrow is shot, effecting the flight.

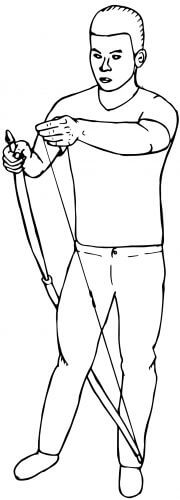

You put three fingers on the string, the index finger above the arrow and the other two below it, known as a Mediterranean draw. However, you don’t grip the string but let it rest lightly against the inside of your first knuckle. As I’ve told a number of my archery students, it’s like plucking a harp string. Some archers do prefer to shoot with three fingers below. There is some evidence that European medieval archers shooting heavy war bows would “lock” their fingers down with their thumb. Some cultures in Asia used a thumb draw instead of their fingers and some Middle Eastern, Eastern European, and Native American cultures use a pinch draw, squeezing the end of the arrow between the index finger and thumb. [1]

Once your fingers are on the string, you sight down the arrow to aim, lining up the arrowhead with your target. Sometimes you must aim higher than your target to account for the distance and drop of the arrow. Then you pull back to your anchor point. It is essential to keep your elbow up to use all your back muscles. Then steady your body as much as possible, do any last minute aiming and relax your fingers to release.

If you are shooting at a distant target, especially if your bow is a lighter poundage, then you will have to raise the bow, usually to a 90º angle. For longer shots, it is common to overdraw, pulling back to touch the chest instead of the face or passed the ear. You must be careful that the tip of your arrow doesn’t get pulled back past the bow.

Here is a helpful video showing how a traditional longbow is shot.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2020 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bow_draw

The Writer’s Guide to Bows: Part 1

Posted on October 16, 2020 4 Comments

Terms & Types

The bow has almost as much mythology surrounding it as the sword. There are several high profile literary and cinematic archers including Katniss Everdeen from “The Hunger Games,” Legolas from “The Lord of the Rings,” and Hawkeye from the Marvel Universe. This, of course, is not getting into the many retellings and remakes of the legend of Robin Hood.

Since the bow is more common in our modern world than the sword and people are more likely to have contact with them, there does seem to be fewer archery misconceptions. However, the biggest thing to remember when writing archery, especially in a medieval or medieval fantasy setting, is that modern archery can vary dramatically from historical and traditional archery.

Most of the information I am presenting comes from practical experience. I have been shooting since 2001 and exclusively use an English longbow and wooden arrows that I make myself.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Writer’s Tip: Since archers usually need to be at a distance from the front line and preferably on higher ground, this could be a great chance for your character to provide an overview of a battle

Terminology

Archery has its own set of terms which can cause a lot of confusion for those unfamiliar with them. Below is a list of basic archery terms.

Limb – The upper and lower arms of the bow. At the end of each limb is the notch for the string. [1]

Grip – The section of the bow where the archer holds it. It’s usually located in the middle between the limbs.

Arrow shelf or arrow rest – A cutaway portion above the grip where the arrow rests. Not all bows have them in which case the arrow rests on the top of the hand gripping the bow.

Nocking point – The spot on the string where the arrow is nocked. Sometimes it is marked by a small metal bead that the arrow is nocked below.

Drawing – The act of pulling back the string of a bow.

Full draw – When the string of the bow is fully pulled back. The modern standard draw length is 28 inches (71 cm).

Serving – A section of the bowstring that is wrapped in thread. It makes that section more durable and able to withstand the wear from nocking and drawing.

Anchor – Once an archer has pulled back to full draw, they normally steady or anchor their hand against their face before releasing. This gives a chance to steady and aim.

Anchor point – A spot on the face that an archer touches when they are anchoring. Anchoring at the same point helps increase accuracy. In the “Hunger Games” movies, Katniss always anchors under her jaw.

Loose – To fire the bow. The archer relaxes their fingers, allowing the bowstring to propel the arrow forward.

Flight – A group of arrows in the air.

Volley – A flight of arrows shot at the same time by a group of archers.

Overdraw – When an archer pulls the string back further than it should be. Usually this means the head of the arrow is pulled back past the bow and the archer’s hand gripping the bow. If the arrow is loosed, it could be shot into the bow or the archer’s hand.

End or butt – A target or a backstop to which a target is affixed.

Quiver – A carrying bag for arrows worn either on the back with a shoulder strap or on the hip, suspended from the belt.

Types of Bows

The two types of bows used during the Middle Ages in Europe were the longbow and the recurve.

The longbow is so named because it is commonly five to six feet (1.5-1.8 m) tall or roughly the height of the archer. When strung it looks D-shaped. The earliest example of a longbow was discovered in the Ötztal Alps in Austria in 1991 with the remains of a natural mummy who was named Ötzi. His body was dated to around 3,300 BC. The bow was made of yew and was 72 inches (1.82 m) long. The longbow was used effectively by the Welsh in their wars against the English. After the English defeated them, they incorporated the longbow into their army, using them in large numbers during the Hundred Years’ War against the French. The longbow played an important part in notable victories such as the battles of Crécy (1346), Poitiers (1356), and Agincourt (1415). [2]

The recurve bow also earned its name from its shape. The middle portion still has a D-shape but the ends of the limbs curve back (recurve) toward the front. It can also be much shorter than a longbow without sacrificing power, making it ideal for mounted archery. This type of bow can generate more energy than a longbow of the same length. Recurves were mainly used throughout the Middle East, portions of Eastern Europe such as Greece and Turkey, North Africa, Asia, and North America. [3]

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2020 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] https://www.tutorialspoint.com/archery/archery_terms.htm [2] "The Efficacy of the Medieval Longbow: A Reply to Kelly DeVries," Archived 2016-01-23 at the Wayback Machine War in History 5, no. 2 (1998): 233-42; idem, "The Battle of Agincourt", The Hundred Years War (Part II): Different Vistas, ed. L. J. Andrew Villalon and Donald J. Kagay (Leiden: Brill, 2008): 37–132. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Longbow [3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Recurve_bow

The Writer’s Guide to Brigandine Armor

Posted on October 9, 2020 8 Comments

This week is my fourth and final installment in my series on common medieval armor.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Writer’s Tip: Even though brigandine armor was common in medieval Europe it is rarely depicted in literary. Including “brig” into your book would be an interesting way to stand out in the plate armor crowd.

Introduction

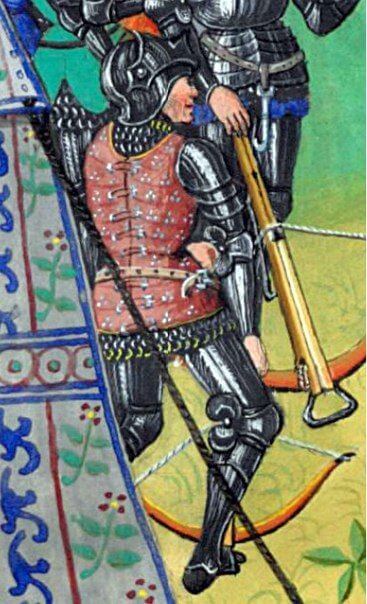

Brigandine is a type of torso armor composed of small rectangular metal plates or bands riveted to an outer layer of heavy cloth, canvas, or leather. It usually has an inner lining. It is generally sleeveless although there is medieval artwork showing brigandine with pauldrons (shoulder armor) and vambraces (forearm armor).

This type of armor is a more refined version of the earlier coat of plates which was worn from the 12th to the 14th century. It followed the same construction of metal pieces riveted between two layers of cloth, canvas, or leather but the plates were much larger. Brigandine came into use during the 14th century and was popular and widely used throughout the 15th and 16th centuries. [1]

Photograph by Gaius Cornelius at the Royal Armoury, Leeds. Photo source.

How It Was Worn

Brigandine was normally worn over a gambeson and hauberk (mail shirt) although it could also be worn with a gambeson with mail voiders. Starting in the mid-15th century the gambeson was replaced with the arming doublet. There are several medieval depictions of brigandine paired with plate limb armor.

It was common across all social classes. Yeomen wore it because it was effective and affordable. Noblemen wore it because they could choose a fancy fabric for the outside. Brigandine was also popular because it did not require a squire to put it on since it normally buckled in the front and because the individual plates allowed for greater movement than plate armor. It was worn by many of the archers during the Hundred Year’s War and they had to have the range of motion to draw a bow.

I have worn brigandine and had no problem shooting a longbow or running in it. I suggest watching Shadiversity’s video here for more information.

Weight

An example of 16th century Italian brigandine in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art tips the scales at 23.4 pounds (10.6 kg). [2] My guess is that this number is probably a good indication of the average weight. [3]

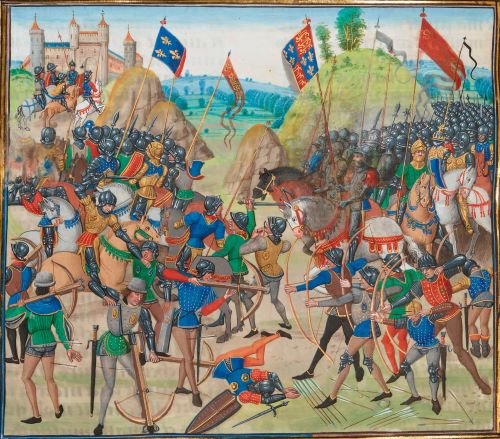

Cost

According to the British historian David Nicolle in his book “French Armies of the Hundred Years War,” a young nobleman would have to spend 125 to 250 livres to fully equipment himself in the best gear. That sum represented eight to sixteen months of wages for an ordinary man-at-arms. He then goes on to say “Salets were valued at between 3 and 4 livres tournois, a jacque, corset or brigandine at 11 livres.” [4] This means a brigandine would cost an ordinary man-at-arms less than a month’s wages. That explains why we see it depicted so commonly in contemporary artwork, like this 15th century painting of the Battle of Agincourt in which all the archers are wearing brigandine beneath their tabards.

Effectiveness and Vulnerabilities

Brigandine armor was effective against most types of attacks although not as protective as plate. Since it is made up of individual plates instead of a solid piece of metal, a person attacking someone wearing brigandine had a higher chance (although probably still not that good) of penetrating between the plates. Also, the plates would flex under a crushing blow although not as much as mail.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2020 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brigandine [2] https://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/71388.html [3] https://www.philamuseum.org/collections/permanent/71388.html [4] https://armstreet.com/news/the-cost-of-plate-armor-in-modern-money

The Writer’s Guide to Plate Armor

Posted on October 2, 2020 99 Comments

This week is the third part in my series about common types of medieval armor. As in my previous posts, I will be pointing out misconceptions.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Introduction

Plate is probably the most iconic type of armor from medieval Europe, conjuring up images of the “knight in shining armor” from fairy tales. Full plate armor had its golden age from the late 15th to the early 16th century. There were multiple styles of plate armor that varied across time and regions and it was not uncommon for soldiers to wear partial suits either to limit the weight or because they could not afford all the pieces.

An early transitional style of armor known as a coat of plate was worn from the 12th to the 14th century and was a rudimentary breastplate made of large metal plates riveted to the inside of a cloth or leather garment and worn over mail. [2] The development of flintlock muskets in the 17th century, which could punch through plate armor at a considerable distance, lead to a decline in its use. The breastplate was the last piece to be employed and was worn by soldiers in the Napoleonic wars to protect them against shrapnel. [1]

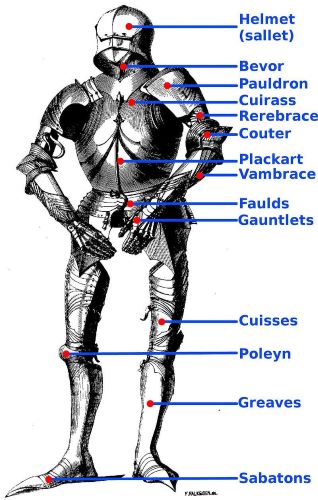

Pieces

The base layer underneath plate armor was an arming doublet and thick woolen hosen or padded legs called cuisses. A full suit of plate armor was made up of the following pieces.

A helmet which could either completely enclose the head such as a bassinet, barbute, armet or close helm, cover only the upper part of the face such as a sallet or be open faced like a burgonet.

The neck was protected by a gorget worn over a bishop’s mantle of mail. If a sallet was being worn it was paired with a bevor that protected the jaw and neck.

A breastplate, also known as a cuirass, protected the chest and historically did not always include the backplate. Bands known as faulds could be attached to the bottom of the breastplate to shield the front of the hips. Bands attached to the bottom of the backplate were known as culets.

Spaulders covered the shoulder and upper arm but not the armpit. The gap could be filled by an extra piece such as a gardbrace, basagew or rondel. A different option was pauldrons, which did cover the armpit and sometimes part of the back and chest.

The elbow was protected by couters and the space between them and the bottom of the shoulder armor was filled by a rarebrace, brassart or upper cannon.

The forearms were covered by the vambraces or lower cannons.

Gauntlets protected the hands and could be a mitten style or have individually articulated fingers. The legs were covered by the cuisse on the thigh, poleyn on the knee and greave on the lower leg. The feet were protected by sabatons or sollerets. For additional protection, armor plates known as tassets could be suspended from the bottom of the breastplate. [3]

Effectiveness and Vulnerabilities

The biggest misconceptions about plate armor are the weight and the effectiveness. I tackled this myth in my introduction to medieval armor which you can find here. Plate armor was highly effective against most medieval weapons although there was some success in developing a heavier bodkin arrowhead that could punch through the thinner plates and in using a heavy bludgeoning weapon to crush in the armor.

There are three main points of vulnerability in a suit of plate: the eye slit, the armpit and the back of the knee. The eye slit on most helmets (unless it’s open face) was quite narrow and usually required either a near-impossible archery shot or being close enough to stab a knife through.

The armpit was vulnerable because it couldn’t be completely protected by armor or the wearer wouldn’t have the range of motion needed to swing a sword. If the person is using a shield and a one-handed arming sword their right armpit is the most vulnerable because it’s not protected by the shield and they expose it every time they raise their arm for a strike.

The back of the knee, like the armpit, is unarmored for freedom of movement. A great literary example of this vulnerability is Pippin stabbing the Witch King in the back of the knee in Tolkien’s “Return of the King.”

Another problem with plate armor is the smoothness of the surface which makes it is more likely to get stuck in mud. There are accounts from the Battle of Agincourt in the Hundred’s Year War of a number of unhorsed knights becoming so mired in the mud that they could not get back up and some even drowned in their helmets.

Writer’s Tip: Knowing the vulnerabilities of plate armor is a great way to injure your character even when your reader thinks they’re safe because they’re wearing armor.

Cost

The cost of plate varied according to the complexity as well as over time. For example, a total suit of armor owned by a knight in 1374 was valued at £16 6s 8d while that owned by Thomas of Woodstock, duke of Gloucester, in 1397 was worth £103. [4] For a more comprehensive list, I suggest the Medieval Price List.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2020 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plate_armour [2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coat_of_plates [3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Components_of_medieval_armour [4] Standards of Living in the Later Middle Ages, Christopher Dyer, Cambridge University Press, 1989.

The Writer’s Guide to Chainmail

Posted on September 25, 2020 11 Comments

This week is the second part in my series about common types of medieval armor. As in my first post, I will be pointing out misconceptions with each type.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Introduction

Chainmail is a type of armor made up of small metal rings linked together and either butted, welded, or riveted closed. The earliest example is from a 3rd century Slovakian burial and it continued to be used on the battlefield in Europe into the 14th century. Chainmail or mail as it was called in medieval Europe, was also used in the Middle East, India, China, Japan, and central and western Asia. In the Ottoman Empire, it was worn by the Janissaries until the 18th century. [1]

Types and Weight

Mail was fashioned into shirts called hauberks in Europe, which could have sleeves of varying lengths or be sleeveless. Their weight depends on the length, the pattern, and the material. The Wallace Collection in London has several hauberks ranging in weight from 9.9 pounds (4.5 kg) for a short sleeved 14th century example to 19.8 pounds (9 kg) for a 15th century long sleeved hauberk. The examples ranged in length from 25 inches (64 cm) to 29 inches (74 cm). Mail was also used to make coifs, which protected the head and neck, and bishop’s mantles, which covered the shoulders. Mail leg armor was known as chausses and could cover the whole leg or just come to the knee and were attached to the arming belt. An example in the Wallace Collection weighs 14 pounds (6.4 kg).

Photo courtesy of Wikipedia. Photo source.

How It Was Worn

Mail was usually worn over a gambeson, which provided protection against chaffing as well as cushioning against bludgeoning or crushing blows. Arming caps were normally worn under coifs and woolen leggings under chausses. In medieval paintings warriors wearing mail coifs have a distinctive “bubblehead” look that is caused by the padding from their arming caps. Chainmail was normally never worn directly over clothing or against the skin because it chafes, snags hair and cloth and the oils used to keep it from rusting rub off onto whatever it is resting against. Early on mail was the primary piece of armor but later into the Middle Ages it was paired with brigandine and pieces of plate armor, such as a breastplate or limb armor.

Putting on Mail

Putting on a hauberk is like putting on a sweatshirt, although obviously it’s a lot heavier. First you get your arms into the sleeves then either bend over or lift the hauberk overhead, getting your head through the opening. As long as it doesn’t get caught it will slide into place. Removing it is a bit trickier. The easiest way is to bend over and pull it over your head, letting it slide off onto the ground. The hauberk will usually end up inside out but thankfully there really isn’t a right side out with a hauberk.

Cost

Since mail is so durable, it was common to pass it down through families. If you did need to buy it, below is a list of what people have paid through history from www.ironskin.com.

11th century Germany: Mail armor is 820 silver coins. A cheap cow is 100.

12th century England: Mail is 100 shillings. A warhorse is 50, a cow 10.

1322 England: A hauberk is 10 marks. A mantle is 1 mark. [2]

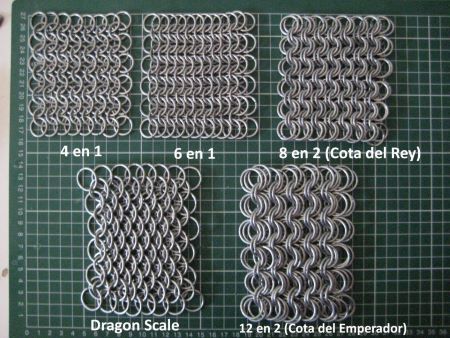

Weaves

The most common pattern of chainmail in medieval Europe was a 4-in-1 weave, meaning one ring was connected to four more, creating a mesh that you can see through. There were however other patterns such as king’s mail, a 9-in-1 or 8-in-2 weave that produces a solid piece. The rings ranged in thickness from 18 to 14 gauge (1.02–1.63 mm diameter).

Effectiveness

Chainmail is effective against slashes and most stabs, depending on the closure style, material, weave density and ring thickness. Weapons with thin points such as the spike at the top of a halberd or a bodkin-tipped arrow were specifically designed to punch through chainmail. This type of armor was also vulnerable to crushing or bludgeoning strikes because of its flexibility.

Earlier chainmail was heavier since it was the primary protection while chainmail from later centuries was lighter because it was often used in conjunction with plate or brigandine. Early chainmail could be heavy enough to withstand a shot from a crossbow. Check out this video of a reproduction 13th century hauberk deflecting a bolt from a crossbow with a 440-pound (200 kg) draw weight! The chainmail weighs 41 pounds (18.7 kg) and the thick rings are made of 2 mm (12 gauge) wire, the thinner rings of 1.5 mm (roughly 14 gauge) wire.

Writer’s Tip: I think it would be fun to have a character get shot with a crossbow bolt and have your readers think they are finished only to have the bolt be deflected.

Special thanks to my friend, Jesse Driskill, for sharing his knowledge.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my newsletter.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2020 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chain_mail [2] https://www.ironskin.com/faq-chainmail-weight-and-cost/

The Writer’s Guide to Gambesons

Posted on September 18, 2020 111 Comments

As promised this week I will be covering types of armor that were common in medieval Europe, starting with gambesons and continuing over the next three weeks with chainmail, plate armor and brigantine. I will also be doing some myth busting with each type of armor. I want to point out that just because I’m covering four types of armor that these were not the only types of armor used in Europe during the Middle Ages. I am merely focusing on the most common ones. There were also other designs and transition styles that were combinations of types of armor.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Introduction

The gambeson or padded jack was a quilted jacket that usually extended to the knees, fastening up the front with lacing, ties, buttons, or buckles. It was commonly stuffed with fabric or horsehair. Since it was easy and economical to make, the gambeson was quite commonly used on its own for protection. It provided decent defense against slashes and bludgeoning. One way to provide more protection when the gambeson was worn alone was the use of jack chains. They were sections of metal that were stitched, tied, or laced to the outside of the gambeson’s sleeves to provide more protection. [1]

How It Was Worn

Gambesons were also the vital first layer under chainmail and plate mail armor, providing cushioning and shock absorption and protecting against chaffing from any of the armor’s edges. They usually had arming points, ties for attaching armor, which helped with the weight distribution. Some gambesons had sections of chainmail attached to the sleeves and armpits called goussets or voiders. This provided more protection, especially to areas that could not be covered with plate armor. [2]

Photo source.

In the mid-15th century the gambeson evolved into the arming doublet, a tightly fitted garment ending at the hips that replaced the arming belt and caused the weight of the leg armor to be carried on the hips and waist rather than the shoulders. [3]

There was also a padded coif or arming cap that was worn on the head underneath chainmail or helmets although it could also be worn alone. The downside to wearing a gambeson was how warm it could become because of its insulating properties.

Cost

I was unable to find any recorded prices for gambesons. However, a freeman in late 12th century England who owned goods valued at less than 10 marks (1 mark = 13s 4d) was required by law to own a helmet, spear, and gambeson. [4] This implies they were relatively cheap. By comparison, a modern gambeson will run you between $115 to $350.

Depictions

Even though gambesons were quite common in the Middle Ages and an essential first layer under armor, they are rarely depicted in television shows or movies or mentioned in historical or fantasy novels. One of the exceptions was Netflix’s “Outlaw King.”

Writer’s Tip: Including rarely depicted armor like gambesons is a great way to show the social standing of your character.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2020 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gambeson [2] https://its-spelled-maille.tumblr.com/post/175518038999/what-is-a-gambeson-its-a-mystery-gambesons [3] http://myarmoury.com/talk/viewtopic.php?p=86991 [4] http://medieval.ucdavis.edu/120D/Money.html English Weapons & Warfare, 449-1660, A. V. B. Norman and Don Pottinger, Barnes & Noble, 1992 (orig. 1966)

The Writer’s Guide to Medieval Armor: Part 2

Posted on September 11, 2020 3 Comments

I hope you enjoyed last week’s post on armor myths because I am covering some more this week.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Leather Armor

Fantasy seems to be in love with leather armor. You can see it from “Vikings” to “The Lord of the Rings” to Dungeons & Dragons. But how prevalent was it during the Middle Ages? An extremely heated debated is raging online.

What we do know is that boiled leather was quite common in medieval Europe and was used to make protective cases for books and delicate instruments such as astrolabes. As for its use in making armor, there are multiple examples of leather limb armor but few of leather torso armor. There are reports of starving soldiers eating their shields and other leather kit like Josephus’ account from the Siege of Jerusalem in 70 AD and advice from a medieval Arab author on coating leather armor with crushed minerals mixed with glue to made it tougher. It is believed the term “cuirass,” referring to armor covering the torso, comes from the French term cuir bouilli, meaning boiled leather. We have few physical examples of medieval leather torso armor but there is uncertainty whether that is due to its scarcity or because they rotted away.

Compounding the problem is a lot of misidentification of armor in medieval paintings. Much of what is thought to be leather or studded leather is in fact brigandine, a type of armor made up of small metal bands or plates riveted to an outer layer of cloth, canvas or leather. In short, the debate still rages. [1]

Expense

The price of armor of course depended on the type, quality, and time period. I will be detailing cost of specific types of armor in their own posts. I will however provide you with some highlights to give you an idea.

Mail during the 12th century cost around 100s. [2] A complete set of knight’s armor in 1374 was valued at £16 6s 8d. Armor owned by the Duke of Gloucester in 1397 was worth £103. [3] A suit of ready-made Milanese armor (meaning it wasn’t tailored) in 1441 was priced at £8 6s 8d while squire’s armor cost £5-6 16s 8d. [4] In 1590, a cuirass of proof (indicating it had been tested against the strongest weapons of the time) with pauldrons would run you 40s while one that had not been proofed would cost 26s 8d. For comparison, a cuirass of pistol-proof with pauldrons in 1624 was priced at £1 6s. [5] For more information as well as medieval prices for many other items, I recommend this website.

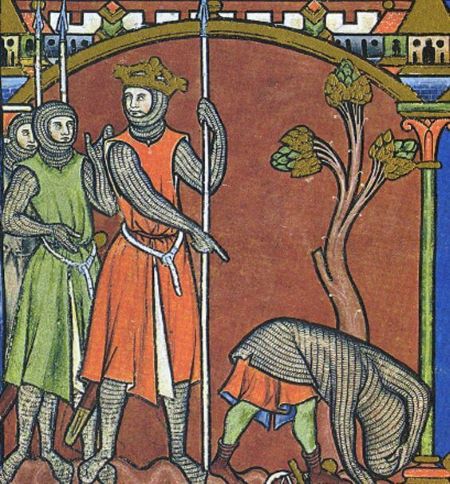

Social Class Limitations

There is a common belief that only knights wore armor. Obviously, the cost would limit who could acquire certain types but we have evidence of non-knightly people owning various types of armor. In fact, it was sometimes the law. In England in 1181 it was mandatory for every freeman who owned goods valued at 10 marks (1 mark = 13s 4d) to have a mail shirt, helmet, and spear. Any freeman poorer than that was required to own a spear, helmet, and gambeson. During the 15th and 16th centuries, soldiers in full plate made up 60-70% of the French army and the percentages were probably similar in other countries. [6] Brigandine was popular with outlaws and highwaymen because it was cheap and easy to make and repair. We also have a lot of artwork from the medieval period showing soldiers in various forms of armor. As you can see in the painting below depicting the 15th century Battle of Crécy, everyone is wearing armor, including the English archers who were commoners and weren’t even worth enough to ransom.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my newsletter.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2020 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boiled_leather [2] The Knight in History, Frances Gies, Harper & Row, New York, 1984 [3] Standards of Living in the Later Middle Ages, Christopher Dyer, Cambridge University Press, 1989 [4] English Weapons & Warfare, 449-1660, A. V. B. Norman and Don Pottinger, Barnes & Noble, 1992 (orig. 1966) [5] The Armourer and his Craft from the XIth to the XVIth Century, Charles ffoulkes, Dover, 1988 (orig. 1912) [6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plate_armour

The Writer’s Guide to Medieval Armor: Part 1

Posted on September 4, 2020 50 Comments

I hope you have been enjoying my posts on swords and other medieval weapons. This week we are moving on to armor myths because, o boy! are there a lot of them. The armor worn in medieval Europe varied across time, region, and social standing. I will be covering common types of armor later.

As always, magic is the exception to the rules. Because magic.

Effectiveness

Obviously, the effectiveness of armor depends heavily on the type of armor and how well it was made. What amazes me is the number of times in movies, TV shows and video games I have seen someone stab straight through armor, include more protective armor like plate mail, without a problem. If armor were that ineffective against a knife stab or a sword slice nobody in the Middle Ages would have bothered wearing it. Plate mail is designed to take an enormous amount of abuse while still protecting the wearer. Chainmail is effective at guarding against slices. If you want to see firsthand how much abuse armor can take, I suggest finding footage of Battle of the Nations, an international medieval combat championship, or watching an episode of History’s “Knight Fight.”

This is not to say however that armor could ward off any blow. For every advance in armor technology there was an advance in weaponry to counter it. When plate armor was developed, a thicker version of the bodkin arrowhead was created that increased the chances of penetrating plate in thinner spots. Usually the only shots that made it through were lucky ones that found the proverbal “clink in the armor.” YouTuber Tod Todeschini of Tod’s Workshop has a fantastic video here about arrows versus armor.

Writer Tip: Your character taking a hit to the armor and shrugging it off could be a great opportunity for them to be thankful they spent the extra money on good armor.

Weight

When most people think of medieval European armor usually their first mental image is of a knight being winched onto his horse because he can’t manage it in his armor on his own. “A Knight’s Tale” has a perfect example of this trope. However, a complete harness of plate armor usually tipped the scales at 33- pounds (15-27 kg). [1] By contrast, an American soldier in World War II was carrying up to 75 pounds (34 kg), which is why so many of them drowned during the D-Day landing. [2] Jousting armor was made substantially heavier to provide as much protection as possible and since the wearer didn’t need to move freely. It could weigh up to 110 pounds (50 kg). Below is a table that shows the average weight of 135 armors from 21 museums. Here is the link to the entire study.

Mobility

The weight of medieval armor was distributed across the body. In the case of plate and brigantine, the pieces were articulated to give the wearer full range of motion. The armor worn on the upper body was suspended from the shoulders and that worn on the lower body from a wide arming belt (or an arming doublet from the mid-15th century onward), causing the waist and hips to carry the weight. Plate was buckled or laced into the gambeson or arming doublet at multiple places to connect it snugly with the wearer, distribute the weight, and make it easier to move. Most armor was custom fit so there was no unnecessary extra weight and the armor conformed to the body. An armored warrior, including on in full plate, could run, jump, fight, and mount his horse unassisted. [3]

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my newsletter.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2020 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Warrior Race: A History of the British at War. James, Lawrence (2003). St. Martin’s Press. P. 119. ISBN 0-312-30737-3. [2] https://www.popularmechanics.com/military/research/a25644619/soldier-weight/ [3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plate_armour

The Writer’s Guide to Medieval Self-Defense Weapons

Posted on August 28, 2020 4 Comments

This week we continue our exploration of common medieval weapons other than the sword with a focus on day-to-day use and self-defense. For those who could afford them, swords were the most popular choice for a self-defense weapon because they are portable, effective, and can be used in close quarters. However, some cities had laws against the wearing of swords above a certain length during times of peace and some people could not afford them. Of course, in pinch, just about anything can be used as a weapon.

Daggers and Knives

Knives, usually defined as short single edged slicing blades, were commonly carried by all social classes in medieval Europe. They were a handy everyday tool for eating, preparing food and trimming quill pens.

Daggers, being double-edged stabbing weapons, were more closely tied to knights and the nobility because the cruciform shape of the weapon matched the shape and style of most arming swords of the period. The earliest depiction of the cross-hilted dagger is from 1120 AD in the “Guido relief” inside the Grossmünster of Zürich. [1] However, as the Middle Ages progressed other versions of the dagger were developed by the lower classes such as the bollock dagger, the ancestor of the Scottish dirk.

Writer’s Tip: It was common for people to carry their eating utensils with them, meaning if you were having a dinner party you were invited a group of armed people into your house. This could be a great start to a medieval whodunit.

Axes and Hatchets

As I mentioned in my previous article, small axes and hatchets were household tools used for cutting wood. Although many men-at-arms carried them into battle, they were also common self and home defense weapons because they were so handy.

Staffs

A basic and easily made weapon also known as a short staff or quarterstaff. Usually fashioned of hardwood and between six to nine feet (1.8 to 2.7 m) in length, the staff was popular across the social spectrum. Swordsmen such as George Silver in the 16th century and Joseph Swetman in the 17th century praised the staff as being among the best, if not the best, of all hand weapons. [2]

Farm Implements

Many tools for farming could be used for self-defense in a pinch. Most were long-handled and were modified over time into polearms. For example, the threshing flail has a long handle with a short heavy wood head with an articulated attachment such as a strap, rope or chain. Originally used to thresh grain, it was brutally effective against people. Another example is the bill hook. Consisting of a curved wide hook sharpened on the inside edge on a haft, it was originally used to trim tree limbs but was good at unhorsing riders. Other examples include pitchforks, scythes, and sickles.

Photo courtesy of Shutterstock.

Courtesy of Shutterstock.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have any questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways please sign up for my email list. To celebrate my first newsletter I will be giving away a copy of “Build Your Author Platform” by Carole Jelen and Michael McCallister, a book that has been invaluable in helping me build my platform. The deadline to sign up to be entered in the drawing is Aug. 30th.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2020 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dagger [2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quarterstaff