The Writer’s Guide to Gunshot Wounds

Gunshot wounds are high-stakes injuries often used to raise tension, shift plot direction, or force characters into survival situations. But in fiction, they’re also frequently misrepresented. A character shrugs off a bullet to the shoulder and runs a mile. Another takes a shot to the gut and delivers a rousing speech while bleeding out. While creative license has its place, writing gunshot wounds with accuracy and thoughtfulness can add realism, drama, and depth to your story.

This guide breaks down how you can realistically portray gunshot injuries, exploring how factors like location, distance, firearm type, caliber, and long-term effects affect the outcome—and how your characters deal with it.

The Big Four Factors That Determine Severity

Location of the Wound

Where the bullet hits is arguably the most important factor in determining severity, pain, survivability, and consequences.

Head: Nearly always fatal unless the bullet grazes or misses vital brain structures. Survivors may suffer permanent cognitive or motor impairments.

Neck: High risk because of arteries, airways, and spinal cord. Can cause death by bleeding, asphyxiation, or paralysis.

Chest/Thorax: May puncture lungs, heart, or major arteries. A collapsed lung (pneumothorax) may be survivable with immediate care. Heart shots are nearly always fatal.

Abdomen: Damage to organs like the liver, intestines, or kidneys can be survivable—but painful, with a risk of sepsis or long recovery.

Arms: Often survivable unless major arteries or nerves are hit.

Legs: Femoral artery injuries bleed out fast. Joint damage can lead to disability.

Shoulder: While common in fiction as a “safe” shot, the shoulder contains nerves, arteries, and the brachial plexus—a hit here is not minor.

There are very few places on the human body where a bullet can go through “cleanly” without serious consequences.

Distance to Target

Distance affects bullet speed, trajectory, and penetration:

Close range: High velocity, massive tissue damage, often with an exit wound. May include burns or stippling (tiny burns from gunpowder).

Medium range: Still deadly, especially with rifles or handguns.

Long range: Less velocity, but high-caliber weapons (e.g., sniper rifles) still deliver lethal damage.

Point-blank: Devastating. Can cause hydrostatic shock (shockwave trauma) or completely shatter bone. A point-blank shotgun blast will not be survivable unless it’s a glancing hit or a specialty shell.

Type of Firearm and Ammunition

Different weapons produce vastly different wounds.

Handguns (e.g., 9mm, .45 ACP): Lower velocity, less tissue destruction than rifles. Good for close-range injuries.

Rifles (e.g., AR-15, AK-47): High-velocity rounds. Bullets can tumble or fragment, causing greater internal damage.

Shotguns: Buckshot is devastating at close range; multiple projectiles spread out. Slugs are large, single projectiles—massive impact, potentially fatal.

Hollow point bullets: Expand on impact, causing large wound channels but usually staying inside the body.

Full metal jacket bullets: May pass through (creating entry and exit wounds), potentially hitting bystanders or walls behind.

Survival doesn’t just depend on the gun—it depends on the bullet.

Caliber and Ballistics

Caliber affects penetration, trauma, and internal injury.

Small calibers (e.g., .22): Less fatal, but can still kill, especially if they ricochet inside the skull or strike vital organs.

Medium calibers (e.g., 9mm, .40): Standard for law enforcement; deadly with proper shot placement.

High calibers (e.g., .50 BMG): Overkill for human targets—more often used in military or sci-fi contexts. Can dismember or explode tissue.

What Happens After the Shot

Immediate Effects

Shock and Pain: Most people go into shock before they even process the pain.

Bleeding: Arterial bleeding spurts. Venous bleeding oozes. Tourniquets and pressure matter.

Adrenaline: May delay the onset of pain or symptoms temporarily.

Mobility: A character can still move after being shot in the leg or shoulder—but they’ll experience slowness, pain, and may leave a blood trail.

Blood Loss: Even minor-sounding injuries (like a hit to the thigh) can cause death in under five minutes if they strike a major artery.

Medical Treatment

First Aid: Pressure, elevation, tourniquet, or chest seals for sucking wounds.

Emergency Care: IV fluids, surgery to repair organs, blood transfusions.

Infection Risk: Especially in gut wounds or if the bullet brings debris with it.

Recovery Time

Minor limb injury: Weeks to months.

Chest or abdominal wound: Months of rehab, possible surgeries.

Major organ damage: Could be lifelong or fatal.

Survival Odds by Location (Generalized)

Head (brain) – < 10% – Usually fatal unless it’s a grazing or peripheral hit

Neck – 10–40% – High risk of bleeding, airway obstruction, or paralysis

Chest – 15–60% – Depends on lung vs heart and access to trauma care

Abdomen – 50–70% – Survival possible with rapid surgical intervention

Arm (upper/lower) – 80–95% – Risks: nerve damage, brachial artery, long-term weakness

Leg (upper/lower) – 70–90% – Femoral artery is the biggest danger

Shoulder – 60–85% – Often survivable but not “minor”

Long-Term Effects

Surviving a gunshot wound often comes with permanent consequences.

Chronic Pain or Disability: Especially from damaged joints or nerves.

Mobility Issues: A leg wound might lead to a limp. A shot arm may never regain full strength.

Mental Trauma: PTSD, survivor’s guilt, fear of enclosed spaces or loud sounds.

Scarring: Exit wounds are often uglier than entry wounds. Characters may carry visible or emotional scars.

Addiction or Dependency: Long recoveries might lead to opioid dependence or depression.

Reputation or Legend: In some genres, surviving a gunshot can turn a character into a symbol, legend, or target.

Depicting Gunshot Wounds Across Genres

Gunshot wounds are a powerful tool in fiction—dramatic, painful, and potentially life-altering. But how you portray a gunshot injury should reflect your story’s genre, setting, and technology level. A gritty crime thriller will handle a bullet wound differently from a space opera or a historical drama. I will examine how genre and time period affect the portrayal of gunshot wounds, ranging from modern realism to speculative fiction, and even show how firearms can be thoughtfully integrated into fantasy settings.

Contemporary

In contemporary fiction—especially in crime, thrillers, or military fiction—realistic detail is key. Readers expect authentic depictions of ballistics, injury severity, emergency response, and long-term recovery.

How Gunshot Wounds Are Depicted

Immediate Pain and Shock: Gunshot victims rarely stay cool and coherent unless they’re heavily trained or in shock.

Medical Intervention Is Essential: A character doesn’t “walk off” a bullet to the chest. Even limb shots may involve arterial bleeding, nerve damage, or bone fractures.

Legal and Procedural Fallout: In contemporary settings, being shot—or shooting someone—comes with police reports, trauma, investigations, and sometimes lawsuits or revenge plots.

Type of Firearm Matters: A .22 caliber handgun causes very different wounds from a shotgun or rifle.

Example: A detective shot in the leg during a raid may survive, but with weeks of rehab and a permanent limp that complicates their return to duty.

Science Fiction

Science fiction opens the door to creative reinterpretations of what a gunshot even is. You’re no longer limited to metal bullets—you might be dealing with plasma rifles, energy blasts, sonic disruptors, or magnetically accelerated projectiles (railguns).

How Gunshot Wounds Are Depicted

High-Energy Trauma: Sci-fi weapons may vaporize tissue, cauterize wounds instantly, or disrupt internal organs without breaking the skin.

Armor and Shields: Characters may wear powered armor or have personal shields that absorb or deflect shots. Injuries might result from concussive force or internal damage despite lack of penetration.

Medical Advancements

Regeneration chambers, nanobots, or synthetic tissue may allow for near-instant healing—or horrifying complications.

Survival may be easier, but psychological trauma and cybernetic replacement arcs still add stakes.

Example: A bounty hunter shot by a plasma bolt survives, but the wound fuses nerves unnaturally. Now they feel heat when it rains—and hear voices that weren’t there before.

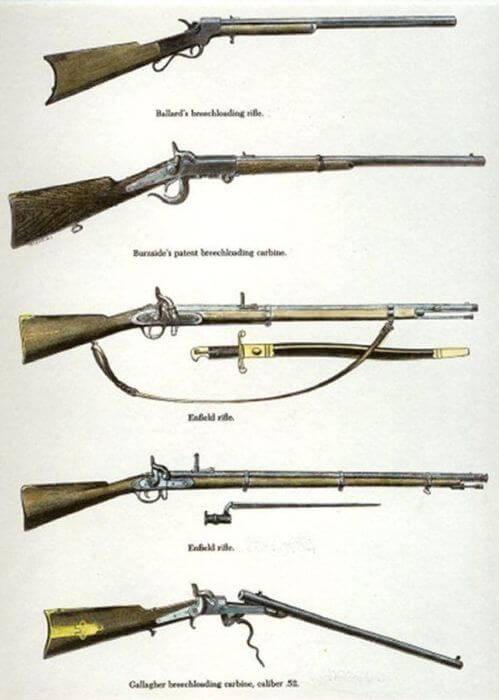

Historical

The setting of your historical novel determines the firearms available, as well as their lethality, reliability, and wound profile. A gunshot in 1750 looks—and behaves—differently from one in 1944.

A Brief History of Firearms

15th–16th centuries – Matchlocks and hand cannons – Inaccurate, slow to reload. Large lead balls cause massive blunt trauma.

17th–18th centuries – Flintlock pistols and muskets – Smoothbore weapons with poor accuracy. Lead balls crush tissue, often lodging inside.

19th century – Percussion cap firearms, revolvers, early rifles – More reliable. Wounds still messy; high risk of infection.

Mid-20th century (WWI/II) – Bolt-action and semi-automatic rifles, machine guns, pistols – Faster fire, high-velocity rounds with through-and-through wounds.

Modern day – Assault rifles, sniper rifles, handguns, shotguns – Wide variation. Modern bullets cause cavitation and fragmentation.

Medical Limitations in Historical Settings

Lack of Sterility: Even a survivable wound might become infected or gangrenous.

Slow Evacuation: A soldier shot on the battlefield might wait hours or days for medical attention.

Crude Surgery: Amputation was common for limb wounds because of shattered bone and infection.

No Anesthesia (Pre-1840s): Treatment was often as traumatic as the wound.

Example: A Revolutionary War soldier shot in the gut is unlikely to survive—not because of the bullet, but because peritonitis (infection of the abdominal lining) sets in.

Fantasy

Though traditional fantasy leans toward swords, bows, and spells, guns can absolutely work in a fantasy setting, especially if the Renaissance, flintlock era, or steampunk aesthetics inspired the world.

Fantasy Gun Concepts

Arcane-Fused Firearms: Guns powered by crystals, runes, or enchanted powder.

Spellshots: Firearms that fire magically infused rounds, such as bullets that explode into flames or frost.

Gunmages: Spellcasters who channel their magic through a firearm, controlling its accuracy, power, or elemental effects.

Dwarven Engineering or Steampunk Invention: Guns as rare, volatile tools available only to skilled inventors or secretive guilds.

Depicting Gunshot Wounds in Fantasy

Magical Medicine vs. Mundane Damage: Does healing magic work on gunshots? Is it treated like any other wound, or do bullets resist spells?

Supernatural Ammunition: Silver bullets for werewolves. Obsidian rounds that curse rather than kill. Bullets that explode with magical energy, damaging both body and spirit.

Example: A rogue fires a single-shot rune-etched pistol at a charging ogre. The bullet strikes true—but the ogre doesn’t fall. The wound glows purple. It was a binding shot, not a killing one.

Treating Gunshot Wounds Through History (and Beyond): From Muskets to Medbays

Gunshot wounds have evolved alongside the weapons that cause them. A lead musket ball from the 1600s causes a very different injury—and demands a very different response—than a modern rifle round or a sci-fi plasma bolt. As firearms developed in power, speed, and availability, so did the medical practices used to treat the wounds they inflicted.

I will walk you through typical gunshot wound treatments across historical eras, then explore how science fiction and fantasy settings might handle firearm injuries within the logic of their worlds.

Early Firearms (15th–17th Centuries): Matchlocks, Muskets, and Mutilation

Early weapons fired slow, heavy lead balls with poor accuracy and low velocity. Rather than piercing cleanly, these flattened on impact, crushing bone and tearing soft tissue. Wounds were messy, blunt-force traumas, often with embedded lead and fabric debris.

Treatments

No understanding of infection or bacteria. People considered gunshot wounds “poisoned” and often cauterized them with boiling oil or hot irons. Amputation was common—especially for limb wounds involving shattered bones. Surgeons would use bone saws, clamps, and alcohol as crude anesthesia (or none). Surgeons applied herbal poultices and salves to “draw out” the damage.

Tip: Characters might fear the surgeon more than the gunshot. Treatment was often as traumatic as the injury itself, and survival depended as much on luck and constitution as care.

18th–19th Centuries: Flintlocks, Revolvers, and Field Medicine

Still using lead balls and black powder, but with improved loading and firing rates. Introduction of rifled barrels increased accuracy and force, leading to deeper penetration. In the Civil War and Napoleonic Wars, limb wounds were overwhelmingly common, but abdominal or chest wounds were usually fatal.

Treatments

Amputation remained the go-to solution for limb wounds, especially in war. Surgeons understood some basic wound cleanliness, but they did not widely use antiseptics until late in that era. By the mid-1800s, surgeons used ether and chloroform as anesthesia. Triage and battlefield hospitals became better organized. They attempted bullet extraction, but it could cause more harm than good.

Tip: A character wounded in battle might survive with a stump, a cane, or lifelong pain. Emotional trauma was often overlooked, but writers can explore the psychological cost of survival.

Early 20th Century: World Wars and Surgical Breakthroughs

Introduction of machine guns, high-velocity rifles, and shrapnel changed the battlefield. Wounds became more complex, involving multiple entry/exit points, fragmentation, and internal damage. Trench warfare led to chronic infections, gangrene, and delayed treatment because of battlefield conditions.

Treatments

Antiseptics and sterilization became standard. Blood transfusions and IV fluids improved survival rates. Field surgery and mobile hospitals advanced. Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928, revolutionizing infection treatment. Psychological care began to address shell shock, a precursor to PTSD care.

Tip: A soldier wounded in WWII might receive battlefield stabilization, evacuation, and multiple surgeries. Long-term effects could include nerve damage, reduced mobility, or mental health challenges.

Late 20th to 21st Century: Modern Firearms and Advanced Trauma Care

Use of hollow point, jacketed, and high-velocity rounds increased the complexity of wounds. Greater understanding of cavitation effects (tissue disruption caused by bullet shockwaves). More gunshot wounds involve multiple bullets, high blood loss, and shattered bones.

Treatments

Rapid-response EMS systems: Stabilization within minutes of injury.

Advanced trauma centers: CT scans, surgical teams, ICU care.

Wound management: Debridement, antibiotics, internal fixation (plates, rods), skin grafts.

Rehabilitation: Physical therapy, prosthetics, and psychological counseling.

Ballistics forensics can determine bullet type, distance, and angle for investigative plots.

Tip: A modern character shot in a major city has a solid survival chance if they receive treatment quickly. Characters may still face months of recovery, complications, or chronic pain.

Science Fiction: Healing Beyond the Bullet

Weapons may include plasma bolts, railguns, lasers, or sonic disruptors. Wounds may cauterize instantly, vaporize tissue, or cause internal organ failure without surface damage.

Treatments

Nanotechnology: Microscopic bots that repair tissue, clean wounds, stop bleeding, and even rebuild organs.

Regeneration chambers: Tanks or beds that stimulate rapid healing using biotechnology.

Artificial implants or cybernetic limbs: Tech can replace destroyed tissue.

Gene therapy: Activate the body’s latent regenerative abilities—at a cost (mutation, fatigue, etc.).

AI-guided medbots: Machines perform surgery or stabilize wounds with precision.

Tip: Even if treatment is instant, consequences matter. Psychological scars, debt from medical services, or technology gone wrong can add rich narrative layers.

Fantasy: When Magic Meets Musket Fire

Though firearms are uncommon in traditional fantasy, they can exist in Renaissance, steampunk, or magic-infused worlds. Whether primitive or enchanted, bullets still break flesh—and characters still bleed.

Fantasy Firearm Types

Runed pistols or flintlock muskets used by arcane rebels. Alchemical guns that shoot elemental bullets. Dwarven-engineered rifles or spellguns used by gunmages.

Treatments

Healing Magic: Basic spells may stop bleeding or close wounds but not regenerate lost blood or organs. High-level magic might regrow tissue, but requires rare ingredients, time, or sacrifice. Some bullets (e.g., cursed, silver, or chaos-infused) might resist healing altogether.

Alchemical Potions and Salves: Quick-healing draughts may numb pain or speed up clotting, but overuse might cause side effects (e.g., addiction, corruption).

Clerics or Priests: Healing tied to divine power or ritual may come with moral or spiritual cost—healing a killer might anger their god.

Traditional Methods: In lower-magic settings, healers treat a gunshot like any wound: with surgery, herbal compresses, cauterization, and hope.

Tip: Treat gunshot wounds as rare and terrifying in low-magic settings, and as manageable but still dramatic in high-magic ones. Either way, make healing cost something.

Plot and Character Ideas

Gunshot wounds offer more than just physical damage—they can change the trajectory of a story, test a character’s morality, resilience, or relationships, and act as a catalyst for revenge, redemption, or transformation. Whether the gunshot is a mistake, a deliberate act, or a consequence of a larger conflict, these moments often carry emotional and narrative weight.

Below are plot and character ideas centered on gunshot wounds, including options for contemporary, historical, fantasy, and science fiction settings.

The Survivor with a Bullet Lodged Inside

Genre: Contemporary, Crime, Thriller

Plot Idea: A character survives a gunshot wound—but the bullet was never removed. Over time, it causes complications, physically and mentally.

Character Angle: The bullet becomes a constant reminder of the trauma. The character develops chronic pain or PTSD, making daily life difficult. They keep the bullet a secret—perhaps it could link them to a crime or reveal their true identity.

The Healer Who Can’t Save Everyone

Genre: Historical, Medical Drama, Fantasy

Plot Idea: A battlefield surgeon, medic, or healer cannot save a wounded soldier because of a gunshot wound they can’t treat in time.

Character Angle: Wracked with guilt, the character becomes obsessed with mastering their craft. They question whether they let the person die on purpose (e.g., a traitor, enemy, or friend). Later, they meet someone else with a similar injury and must face the trauma all over again.

A Case of Mistaken Gunfire

Genre: Detective, Noir, Contemporary Thriller

Plot Idea: A character accidentally shoots someone they thought was a threat, only to realize the victim was innocent.

Character Angle: They spiral into self-loathing or become obsessed with atonement. Someone witnessed the shooting and used it for blackmail or revenge. The wound didn’t kill the victim—but the person is now paralyzed or changed forever.

The Ghost Bullet

Genre: Science Fiction, Mystery

Plot Idea: A gunshot injures a character—but investigators find no shooter and recover no bullet.

Character Angle: They suspect advanced or alien tech targeted them. They experience strange symptoms, like enhanced senses, hallucinations, or embedded nanotech. As they investigate, they uncover a government experiment or secret war.

The Magic That Can’t Heal a Bullet

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A gun is a rare, magical artifact in a high-fantasy setting. Someone shot a character, but the wound did not respond to magical healing.

Character Angle: A curse, enchantment, or otherworldly power might affect the bullet. The wounded character must undertake a quest to find a magical remedy—or die slowly. The wound grants visions or abilities—but only if they survive long enough to understand them.

The Assassin’s Doubt

Genre: Thriller, Espionage

Plot Idea: A professional hitman shoots their target—but the victim survives against all odds and disappears.

Character Angle: The assassin becomes obsessed with finishing the job—or figuring out why they couldn’t. The survivor may now have a personal vendetta, becoming the hunter. Was the miss intentional? Subconscious doubt, a misfire, or a planted distraction?

The Soldier’s Second Life

Genre: Historical, Military, Contemporary

Plot Idea: A soldier is presumed dead after being shot and left on the battlefield but survives against all odds.

Upon returning home, they find authorities declared them dead, their spouse remarried, or someone sold their home. They struggle with identity, PTSD, and reintegration, while their survival story becomes legend or political controversy. They later discover the person who shot them was a friend—or an ally turned traitor.

The Scapegoat

Genre: Mystery, Legal Drama, Crime

Plot Idea: During a high-profile crime—a robbery, protest, or riot—someone shoots a character, then frames another person for it.

Character Angle: The victim can’t remember who shot them but slowly regains memory. The shooter was someone they trusted—or were ordered to protect. The character must choose between protecting someone they love or revealing the truth.

The Clean Shot That Should’ve Killed

Genre: Science Fiction, Supernatural

Plot Idea: Someone shot a character point-blank, but miraculously, the character survived—not through luck, but because something unnatural intervened.

Character Angle: The character heals too quickly and questions their humanity. They experience visions, altered perceptions, or unexplainable abilities. Was the shooter part of a secret group testing superhuman resilience?

A Wound Shared Across Worlds

Genre: Fantasy, Portal Fantasy

Plot Idea: A character, shot in our world, wakes up in a fantasy realm; magical healing cannot stop the bleeding wound.

Character Angle: The injury links them to another version of themselves who is being hunted in the other world. The wound is the key to traveling between realms. Every time it bleeds, they shift realities or uncover part of a prophecy.

The Keepsake Bullet

Genre: Romance, Historical, Thriller

Plot Idea: A character carries a bullet that was removed from their body—a reminder of something (or someone) they can’t forget.

Character Angle: The bullet is from a lover, a betrayal, or a war. They wear it as a necklace, charm, or hidden in their clothing. When confronted by the past, they must choose to seek revenge, closure, or peace.

The Legendary Survivor

Genre: Western, War Story, Urban Myth

Plot Idea: A character survives a nearly fatal gunshot and becomes a local legend—but the truth behind the wound is more complicated.

Character Angle: People exaggerate the story, and the character must live up to (or dismantle) the myth. The injury gave them a second chance at life, and now they seek justice, not vengeance. Their own child, best friend, or former student fired the bullet—and no one else knows.

Contextualize firearms and the wounds they inflict within your genre and setting. A shot that instantly kills in one world might merely disorient in another. Consider not just what the gun does, but how it fits into the world, and how your character deals with the consequences.

Gunshot wounds can be more than just a plot point. They can be the heart of a story, shaping everything from character motivation to thematic tone. Whether you’re writing about revenge, survival, transformation, or redemption, using a gunshot wound as a catalyst gives you an opportunity to explore pain, resilience, and choice at their most visceral.

A bullet wound leaves a scar. Make sure the story does too.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

Excellent info and advice, thanks a lot! Just what I needed for my historical novel.

LikeLike

Excellent! I’m so glad I could help.

LikeLike

Some great pointers, and this is information I could really use. Great work and thank you.

LikeLike