The Writer’s Guide to Torn Ligaments and Tendons

Not all dramatic injuries involve swords, bullets, or fire. Some of the most debilitating and narratively useful injuries are the ones that don’t look dramatic at all: torn ligaments and tendons. A character may walk away from a fall, jump, or sudden movement looking fine, only to discover their body won’t support them when they need it most.

For writers, understanding how these injuries occur, what they look like, and how they heal can add realism and tension to both everyday stories and high-stakes adventures.

Definition

Ligaments are bands of tissue that connect bone to bone, stabilizing joints.

Tendons are connective tissue that attach muscles to bone, transmitting the force that moves the skeleton.

Both can stretch, partially tear, or completely rupture because of trauma or overuse. These injuries can sideline a character for weeks, months, or even permanently, especially if left untreated.

Types of Injuries

Ligament Tears (Sprains)

Common in the knee (ACL, MCL, LCL, PCL) and ankle.

Classified by severity:

Grade I: Stretching, micro-tears.

Grade II: Partial tear, joint instability.

Grade III: Complete rupture, joint may give way entirely.

Tendon Tears (Strains)

Common in the Achilles tendon, rotator cuff, biceps, hamstring.

Can be acute (from a sudden force) or chronic (from overuse).

A complete rupture often feels or sounds like a “pop” followed by sudden weakness.

Signs and Symptoms

Sudden sharp pain at the site of injury

Swelling and bruising (may appear after hours)

Inability to bear weight (ankle/knee) or lift (shoulder/biceps)

A joint that feels unstable or “gives out”

A noticeable gap or deformity in severe tendon ruptures

Loss of function: a knee that buckles, a hand that can’t grip, a foot that won’t push off

Dangers

Loss of mobility: Characters may no longer run, fight, or climb until healed.

Reinjury risk: Untreated or poorly healed tears are prone to repeat damage.

Permanent disability: A completely ruptured tendon or ligament can leave long-term weakness if not surgically repaired.

Compensatory injuries: Overuse of the opposite limb can create a cycle of fresh injuries.

For writers, this makes torn ligaments and tendons excellent “hidden cost” injuries: they’re not always fatal, but can permanently alter a character’s path.

Rehabilitation Process

Rehabilitation is long and grueling, often lasting months.

Early stage: Immobilization and gentle movement to avoid stiffness.

Middle stage: Gradual strengthening and physical therapy.

Late stage: Return to full activity, often with bracing or taping for protection.

Recovery Timeline

Minor sprains/tears: 4–6 weeks

Major tears with surgery: 6–12 months

Some never regain full pre-injury strength or mobility

Writer’s Toolkit

Avoid instant recovery clichés: A torn ACL doesn’t heal in a week.

Use realism to raise stakes: A hero with a knee that gives out mid-chase can completely shift the outcome of a scene.

Show the emotional weight: Long recovery periods can mean missed opportunities, sidelined careers, or guilt for slowing down a team.

Let recovery leave scars: Even with healing, a character may always wear a brace, avoid certain movements, or carry a limp.

Use recovery as part of the story arc: A character struggling to relearn how to walk, climb, or wield a weapon creates natural opportunities for conflict, frustration, and growth.

Depicting Torn Ligaments and Tendons Across Genres

Ligament and tendon injuries may not be as flashy as sword wounds or gunshots, but they can be devastatingly realistic obstacles. Because they compromise movement and stability, they’re often story-changing injuries: when a strong character can no longer rely on their body. How you portray them depends heavily on the genre, cause, and treatment available in your world.

Contemporary Fiction

How They Occur

Sports: Common in football, basketball, gymnastics, soccer (e.g., ACL tears, Achilles ruptures).

Accidents: Slips and falls, car crashes, awkward landings.

Occupational injuries: Heavy lifting or repetitive strain.

Depiction Notes

Readers expect medical realism: MRIs, surgeries, physical therapy, and long recovery timelines.

The emotional impact is tremendous. Athletes, dancers, or soldiers may face career-ending injuries.

Writers should show pain and instability realistically (sharp pain, joint “giving way,” long rehab).

Narrative Opportunities

The injury can sideline a protagonist at a crucial time (trial, competition, pursuit).

It can also serve as a metaphor for vulnerability in otherwise strong characters.

Example: A ballet dancer tears her Achilles tendon days before a breakthrough performance. Her artistic identity is suddenly shattered.

Historical Fiction

How They Occur

Battlefield injuries: Slipping in armor, twisting while swinging weapons, or falls from horses.

Agricultural/physical labor: Overstraining while lifting or repetitive fieldwork.

Accidents: Tumbles from scaffolding, carts, or ships.

Depiction Notes

People in the past described these injuries as “lamed” or “crippled” because they didn’t understand ligaments and tendons anatomically.

Without surgery or advanced rehab, complete ruptures meant permanent disability (limping, loss of grip strength, or inability to fight).

Treatments would be limited to rest, herbal poultices, and crude splints/braces.

Narrative Opportunities

A knight or soldier with a torn ligament might become a mentor or strategist instead of a warrior.

In peasant life, it could mean loss of livelihood and deepening poverty.

Creates realism in depicting the long-term costs of battle or hard labor.

Example: A medieval archer tears a shoulder tendon during training. Without effective treatment, he loses his profession and must find a new path.

Fantasy

How They Occur

Overexertion in combat or training (vaulting, rolling, sudden impacts).

Magical beasts: being thrown by a giant, yanked by a wyvern’s tail, or strained while pulling someone from danger.

Cursed or enchanted injuries that mimic ligament/tendon ruptures.

Depiction Notes

Healing options vary.

Low-magic settings: Similar to historical. Permanent disability or slow recovery.

High-magic settings: Potions or spells might instantly knit connective tissue but perhaps at a cost (shortened lifespan, magical scars, debt to the caster).

Even in magical settings, consider limits: maybe magic can mend bone but not restore tendon elasticity.

Narrative Opportunities

Use the injury to highlight team dynamics: does the group slow down to care for the injured, or abandon them?

A mage who tears a tendon in their hand might lose access to gesture-based spells until healed.

The injury could force creative adaptations: learning to fight differently, using magic as a crutch, or training a companion to step up.

Example: A ranger tears his knee ligament while evading orcs. Even with magical salves, he walks with a limp, a reminder of the raid that haunts him.

Science Fiction

How They Occur

Overexertion in low gravity (tendons overstretch without normal resistance).

Industrial accidents in mining colonies or spaceship repair.

Exosuit malfunction straining joints beyond natural limits.

Alien environments where gravity, atmosphere, or physiology make tendons more vulnerable.

Depiction Notes

Advanced medicine might mean:

Nanotech repairs that regrow tissue at the cellular level.

Bioengineered replacements are stronger than human originals.

Exoskeletal supports while ligaments heal.

But tech could fail, be unavailable, or create side effects: over-engineered tendons that tear surrounding tissue, cybernetic replacements that alienate the character from their humanity.

Narrative Opportunities

Injury becomes a resource scarcity plot: who gets the last nanotech injection?

Explores trans-humanist questions. Does a person remain themselves if they replace most of their body?

Injury could also be a disguise: a spy fakes a torn tendon to mask enhanced cybernetic strength.

Example: A soldier tears her Achilles tendon during a mission on a high-gravity world. Med drones offer a cybernetic replacement, but at the cost of her military discharge and human identity.

Treatments for Torn Ligaments and Tendons Across Genres

Torn ligaments and tendons may not be as bloody as a sword wound, but they are life-changing injuries. A complete rupture can take someone from warrior, dancer, or athlete to disabled in an instant. How your story treats these injuries will depend heavily on the era, culture, and technology of your world.

Ancient World

Ancient physicians didn’t distinguish between sprains, fractures, or tendon ruptures. They simply recognized that joints could become unstable, swollen, and painful. People often explained injuries through humors or divine punishment.

Treatments

Rest and immobilization: Splints or bindings made from reeds, leather straps, or linen.

Poultices and compresses: Herbal salves like comfrey (“bone-knit”), honey, or oils to “draw out swelling.”

Massage and stretching: Egyptian and Greek healers often prescribed manipulation to “restore balance.”

Spiritual or ritual healing: Prayers, amulets, or offerings to deities associated with strength or health.

Limitations

Severe tendon or ligament ruptures were usually permanent disabilities. Characters might limp, favor one arm, or retire from combat or hard labor.

Middle Ages

People viewed injuries through humoral theory: swelling was “heat and wet” trapped in the joint. Surgeons and barber-surgeons could treat broken bones, but their understanding of connective tissue injuries was limited .

Treatments

Binding and bracing: Stiff bandages, splints of wood or bone.

Topical remedies: Vinegar, rosewater, or poultices with herbs like yarrow or chamomile.

Bleeding or purging: Sometimes prescribed to “balance humors,” weakening the patient further.

Rest: Immobilization of the joint, often for weeks.

Limitations

Severe tendon ruptures or torn ligaments often resulted in crippling disabilities. Without surgical repair, a torn Achilles tendon or knee ligament could end mobility for life.

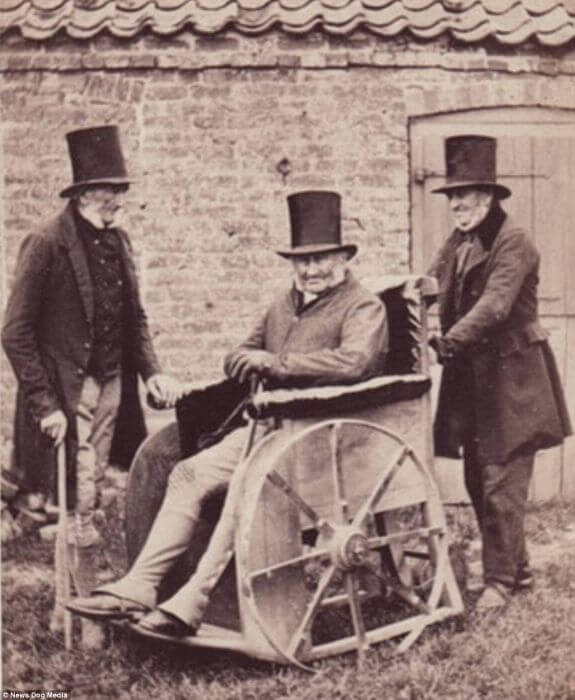

18th and 19th Centuries

Anatomy studies improved. Surgeons identified ligaments and tendons more precisely. However, surgical repair was still primitive, and infection was a major risk before antiseptics.

Treatments

Immobilization: Wooden splints, braces, or plaster casts (plaster casts became common by the mid-19th century).

Pain management: Opium or alcohol.

Surgery: Rarely attempted, but some tendon repairs were crudely stitched. Survival often depended on avoiding infection.

Rehabilitation: Gentle stretching or massage, though people often misunderstood “rehab.”

Limitations

Even with repair, outcomes were uncertain. Many soldiers, sailors, or laborers with severe tears were discharged by their employers because they were permanently disabled.

Modern and Contemporary Medicine

Advanced imaging (MRI, ultrasound) allows precise diagnosis. Surgical techniques and physical therapy have revolutionized outcomes.

Treatments

Non-surgical care: Minor sprains/tears treated with R.I.C.E. (Rest, Ice, Compression, Elevation), bracing, and physiotherapy.

Surgery: Tendon reattachment with sutures, ligament reconstruction (e.g., ACL replacement with graft tissue).

Rehabilitation: Carefully staged rehab lasting months; emphasis on restoring strength and stability.

Prognosis: Many patients regain full function, though some never return to pre-injury performance.

Fantasy

Herbal Remedies: Rare plants that accelerate tissue knitting or reduce swelling dramatically.

Alchemy: Potions that restore connective tissue elasticity but perhaps shorten lifespan or leave “weakened spots” vulnerable to re-injury.

Healing Magic

Instant regeneration spells that reweave torn fibers.

Limitations: healing might consume the caster’s energy, work only once per injury, or leave magical scars.

Some spells may heal bone but not tendon or ligament, forcing creative problem-solving.

Divine Intervention: Priests or holy relics may restore use of a joint but only to those deemed worthy.

Tension for Writers

Magic should not erase stakes. Even with powerful healing, decide whether scars remain, recovery is exhausting, or side effects shape future choices.

Science Fiction

Nanotechnology: Nanobots injected into the bloodstream stitch torn fibers at the molecular level.

Synthetic Replacements: Bio-engineered ligaments or tendons stronger than the originals.

Exoskeletal Supports: Temporary robotic braces allow full mobility while natural healing occurs.

Tissue Printing: 3D bio-printers regrow tendons/ligaments using stem cells.

Gene Therapy: Enhances healing speed, though at risk of cancerous overgrowth or mutations.

Tension for Writers

Futuristic medicine may tempt characters to enhance themselves rather than heal naturally, raising ethical and identity-driven conflicts.

Plot and Character Ideas

The Final Routine

Genre: Contemporary Sports Drama

Plot Idea: A competitive gymnast tears her ACL during a qualifying event for the national team. Her injury sidelines her just as she’s about to achieve her lifelong dream.

Character Angle: Defined by discipline and control, she must navigate life outside the sport while grappling with her identity.

Twist(s): She becomes a coach for a rival athlete, forcing her to confront jealousy and redefine what “winning” means.

The Step Down

Genre: Crime Thriller

Plot Idea: A police detective tears his Achilles tendon chasing a suspect. Stuck on desk duty, he uncovers corruption within his own department.

Character Angle: Used to action, he struggles with immobility and forced patience, but his investigative skills sharpen.

Twist(s): His injury wasn’t accidental. Another cop tipped the suspect off, leading him to the heart of the conspiracy.

The Archer’s Silence

Genre: Medieval Military Drama

Plot Idea: A master archer tears a shoulder tendon during a siege, leaving him unable to draw his bow at a critical moment.

Character Angle: Once a proud symbol of his village’s skill, he’s forced into the role of strategist and teacher.

Twist(s): His apprentice, previously dismissed as too weak, becomes the hero who lands the decisive shot.

The Broken Rider

Genre: 19th-Century Western

Plot Idea: A cowboy is thrown from his horse and tears a knee ligament during a cattle drive. The drive must continue, but he can barely walk.

Character Angle: Proud and stubborn, he refuses to admit his weakness and endangers the crew.

Twist(s): His refusal to stop sparks a mutiny among the drovers, testing loyalty more than cattle rustlers ever could.

The Crippled Blade

Genre: Epic Fantasy

Plot Idea: A renowned swordsman suffers a torn shoulder tendon mid-duel, ending his fighting career. But when war breaks out, the kingdom still demands his service.

Character Angle: He must adapt from warrior to tactician, struggling with bitterness over lost glory.

Twist(s): His knowledge as a duelist gives him an edge as a commander, but his old enemy spreads rumors he’s cursed, undermining his leadership.

Mage’s Grip

Genre: Dark Fantasy

Plot Idea: A spellcaster tears a tendon in their hand during a brutal ritual, crippling their ability to perform gestures required for magic.

Character Angle: Once powerful, now dependent on apprentices to channel spells, they face a humiliating fall from power.

Twist(s): They discover a way to cast spells without gestures by channeling raw willpower, but it corrupts their mind each time they use it.

The Deserted Scout

Genre: Survival Fantasy

Plot Idea: A ranger on a desert mission tears his knee ligament while escaping a sand beast. Stranded and unable to move quickly, he must survive until help arrives.

Character Angle: Fiercely independent, the ranger resents relying on others, especially a green recruit who refuses to abandon him.

Twist(s): The recruit is secretly a spy ordered to ensure the ranger never returns.

Gravity’s Cost

Genre: Sci-Fi Exploration

Plot Idea: On a high-gravity planet, a soldier ruptures his Achilles tendon while running. Without access to advanced med-tech, the team must improvise a brace while under alien attack.

Character Angle: He prides himself on being the strongest of the group, but now must trust others to carry him.

Twist(s): The alien attackers, sensing weakness, are drawn to his injury, not the team.

The Augment’s Failure

Genre: Cyberpunk Thriller

Plot Idea: A street runner with biomechanical tendon replacements has one snap mid-chase. He discovers the corporation that built him has intentionally sabotaged his body.

Character Angle: Once proud of his enhancements, he now feels betrayed by the very tech he relied on.

Twist(s): The failure wasn’t sabotage, it was a built-in failsafe to keep him under corporate control.

Voidwalker’s Limp

Genre: Space Opera

Plot Idea: A pilot tears shoulder ligaments during evasive maneuvers in zero-G, leaving them grounded just before a massive battle.

Character Angle: The pilot struggles with guilt as others fight in their place, haunted by the belief they abandoned their squad.

Twist(s): Their injury saves them, keeping them alive to lead a desperate counteroffensive later.

The Silent Partner

Genre: Mystery / Contemporary

Plot Idea: A violinist suffers a tendon rupture in her hand, silencing her career. But when her partner is murdered, her knowledge of the music world helps her uncover the truth.

Character Angle: Defined by her art, she must repurpose her skills – keen hearing, attention to rhythm, and discipline – into detective work.

Twist(s): The murderer is her understudy, who orchestrated the injury by tampering with her instrument.

The Reluctant Heir

Genre: Fantasy / Historical Blend

Plot Idea: An heir to a warlord’s throne tears a knee ligament in training, casting doubt on their ability to lead in battle.

Character Angle: Desperate to prove worth, they mask the injury while navigating deadly court politics.

Twist(s): Their physical weakness forces them to pursue diplomacy over war, and they succeed where their father never could.

Torn ligaments and tendons are excellent narrative devices because they’re non-lethal but life-altering. They test endurance, patience, and identity just as much as physical strength. Whether you’re writing a soldier, athlete, mage, or astronaut, depicting these injuries realistically grounds your story and deepens your character’s journey.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

I love these guides

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike