The Writer’s Guide to Women on the Battlefield

Posted on April 1, 2022 6 Comments

When you find historical mentions of women on the battlefield, it is usually in the role of nurse or support staff or as a grieving widow. On the rare occasion you find a female soldier, she is disguising her gender or relegated to a non-combat role, such as morale-booster or tactician.

As writers, especially those of us in the fantasy genre, we do not have to be confined by history. It does, however, help to make our writing realistic. So, could women fight effectively on the battlefield? Definitely.

I encourage you to read my Writer’s Guide to Women in Combat and my Writer’s Guide to Women in Single Combat.

As always, magic is the exception to the rule. Because magic.

Strength in Numbers

The biggest advantage that women have as part of an army is the strength of numbers. A smaller, weaker woman (or man, for that matter) is at less of a disadvantage when surrounded by the other members of her unit. This is especially true if there is strong unit cohesion, and the members work to protect each other.

The best situation would be units with a mix of men and women, as well as soldiers of varying strength, height, weight, reach, and skill. This way, the weakness of each soldier is balanced out by the strengths of their fellow soldiers.

However, even in an entirely female unit, the strength of numbers is still an advantage. Again, this is amplified by strong unit cohesion.

If your army is using weapons of any sophistication, the challenges facing your woman warrior are diminished even further. This is especially true if she has modern firearms, advanced futuristic weapons or powerful magic.

Collaborative vs. Competitive

One of the big differences between the sexes is how they react to their teammates. Men are competitive and will push themselves to be better than the other soldiers in their unit. Women, however, are collaborative and will cheer on their teammates. It’s possible that this tendency could lead to stronger unit cohesion in an entirely female unit than an entirely male unit.

Advantages to Having Women in Your Army

There are some advantages to having women in your army. If your soldiers are interacting with the locals, especially women, your female fighters will be more successful at building relationships. This could result in alliances, intelligence, and recruitment. An example is the US Marines’ use of female Marines to search local women at checkpoints. [1] This prevented culture tension but still got the job done.

Women can also be extremely passionate when fighting for a cause, especially if it taps into their nurturing instincts. One of my favorite examples is Akashinga, an all-female unit of park rangers that protect the wildlife in Zimbabwe’s Phundundu Wildlife Park from poachers. These women are armed and trained in combat. Since October 2017, they have been involved in 72 arrests. [2] The name they picked for their unit means “the Brave Ones” in Shona.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2022 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Dr. Regina T. Akers (2009-03-19). "Women in the military: In and Out of Harm's Way". Dcmilitary.com. Retrieved 2012-02-09. [2] https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20180926-akashinga-all-women-rangers-in-africa-fighting-poaching

Posted on March 21, 2022 54 Comments

Starting this week, I will be publishing blog articles every other Friday instead of weekly. I will be posting other content on the off weeks. I decided to make this change because last week I started plotting my second novel. Please stay tuned for more exciting news coming soon.

Writer’s Deep Dive: Joan of Arc

Posted on March 18, 2022 15 Comments

When you ask people for a list of famous women warriors, Joan of Arc is probably in the top five. She casts a long shadow over French history and the image of a woman leading an army into battle is a visceral one that has inspired many writers.

Now, let’s dive in!

The Basics

Joan of Arc, or Jeanne d’Arc in French, was born around 1412 in the village of Domrémy in the Lorraine region of France to Jacques d’Arc and Isabelle Romée. [1] Her family owned a farm and her father was a village official.

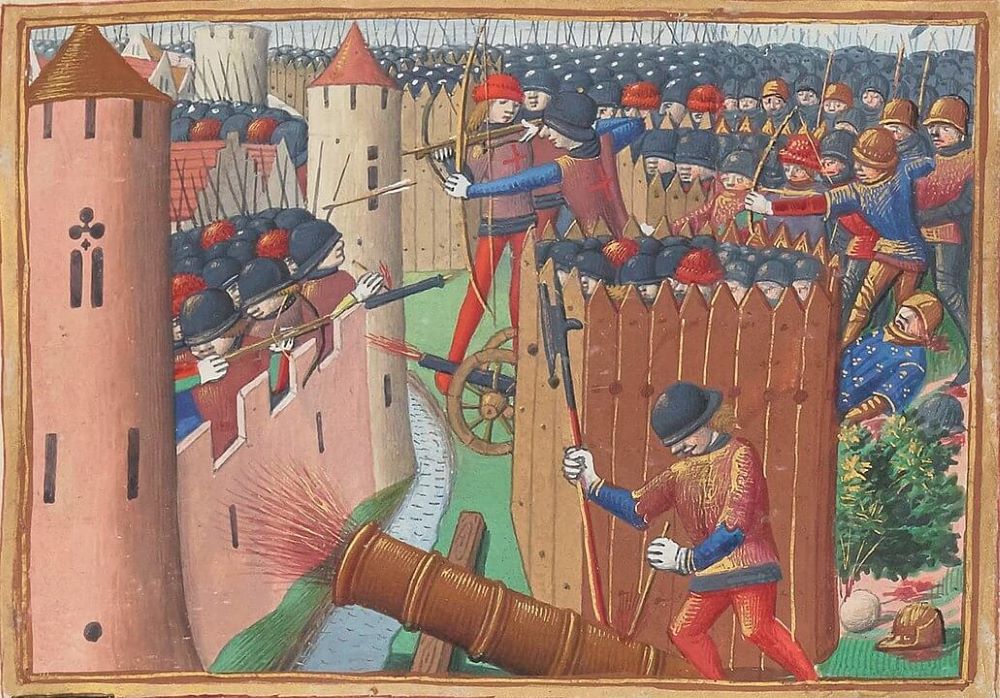

During this period, France was embroiled in the Hundred Year’s War with England, which had begun in 1337. [2] There was also a civil war between two French factions, Armagnacs and the Burgundians. The Burgundians allied with the English and between them conquered half of France. The leader of the Armagnacs and heir to the throne, Charles VII, was outnumbered and cut off. All four of his older brothers had been killed. [3] The war had a personal impact on Joan because the region around her village was raided by the Burgundians.

Around 1425, at thirteen, Joan received her first vision in her father’s garden. [4] Saint Michael the Archangel, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, and Saint Margaret of Antioch appeared to her and instructed her to help the prince and get him crowned at Reimes.

In May 1428, she petitioned the garrison commander of the town of Vaucouleurs, Robert de Baudricourt, for soldiers to escort her to the royal court at Chinon. [5] He refused her. She returned in January, when he again refused her, then in February with the support of two of his soldiers. He was finally swayed by her and the enthusiasm of his men. She traveled with an escort of six soldiers and swapped out her dress for a soldier’s outfit as protection against rape if they should be attacked. [6]

Joan arrived at the town of Chinon in late February or early March 1429. When she entered the court, she looked at the man sitting on the throne and knew he wasn’t the prince. She picked the prince out of the crowd where he had disguised himself. Charles was incredibly moved by her in a following private conversation. [7] He had armor and a banner made for her and she was sent to the besieged city of Orléans.

She was originally meant to be a morale booster, but not actually in command. When she arrived at Orleans, she was left out of the military meetings. [8] On May 4th, she learned that the French forces were attacking the outlying fortress of Saint Loup. She mounted her horse, took up her banner, and rode out to the battle. She found the Armagnacs retreating, but she rallied them and they took the fortress. [9]

Over the next year, Joan led the Armagnac forces in a series of victories, although she did not directly take part in the fighting and killed no one, preferring to command and inspire the troops. Many times, the military commanders urged delay while she urged aggressive advance. Every time they followed her plan, they won. The army cleared a path to Reimes and on July 16th, 1429, Charles was crowned king with Joan in a place of honor. [10]

In the spring of 1430, the Burgundians, who were allied with the English, began attacking towns loyal to the king and laid siege to Compiègne. Joan led a relief force, but they were attacked by the Burgundians and Joan was captured. [11] She was turned over to the English.

She was put on trial for heresy on January 9th, 1431. [12] The entire proceeding was a politically driven sham and the jury was packed with pro-English clergy. Despite that, Joan showed incredible shrewdness in her answers, repeatedly side-stepping verbal traps they set for her. She was condemned of heresy but was told she would be spared execution if she signed a document. Since she was illiterate and it was written in Latin, she did not know she had signed an adjuration, renouncing all her claims. [13]

Afterward, she was returned to English custody where she was chained, mistreated, and suffered repeated attempts by the guards to rape her. [14] Her soldier’s outfit, which had been previously taken from her, was returned. She began wearing it to protect herself from the advances of the guards. Unfortunately, it was all the proof the English needed that she had relapsed in her heresy. When the English bishop who had headed her trial demanded that she renounce her visions and claims, she refused.[15]

On May 30th, 1431, Joan was taken to Rouen’s marketplace, tied to a pillar, and burned to death. [16] Her charred remains were thrown into the Seine River. She was nineteen years old.

The Write Angle

For writers, Joan of Arc is another source of inspiration when writing women warriors leading armies. It is clear from Joan’s string of military successes that she had a keen grasp of military strategy and tactics. Yet on her mission to relieve Compiègne, she disbanded all but four hundred men of her army because she was struggling to feed them. Usually, medieval armies relied on the countryside to supply them with food and water, but in this case, it could not. This is a great example of how critical it was for armies to be properly supplied and to leave nothing up to chance.

Joan is also a great example of the power of inspiration. Before she arrived at the royal court, the prince and his supporters were teetering on the edge of defeat. Over half of France was controlled by the English and Burgundians, and they had not had a significant victory in a generation. Yet Joan sparked a pride and ferocity in them that drove them to victory after victory. Even after her death, the Armagnacs continued fighting with a vengeance, turning the tide of the war. In 1435, the Burgundians signed the Treaty of Arras, formally abandoning their alliance with the English, and the English were driven out of all of France except Calais after the Battle of Castillon in 1453.

Joan was canonized in the Roman Catholic Church and is one of the patron saints of France and female warriors.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2022 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] DLP 2021: Domrémy-La-Pucelle est situé en Lorraine, dans l'ouest du département des Vosges ... dans la vallée de la Meuse. [Domrémy-La-Pucelle is located in Lorraine, in the western part of the Vosges department ... in the Meuse valley]; Gies 1981, p. 10. [2] Lace, William W. (1994). The Hundreds' Year War. Lucent Books. ISBN 1560062339. OCLC 1256248285. [3] Pernoud, Régine; Clin, Marie-Véronique (1999) [1986]. Wheeler, Bonnie (ed.). Joan of Arc: Her Story. Translated by duQuesnay Adams, Jeremy. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-21442-5. OCLC 1035889959. [4] Sackville-West, Victoria (1936). Saint Joan of Arc. Athenium. OCLC 1151167808. [5] Pernoud, Régine; Clin, Marie-Véronique (1999) [1986]. Wheeler, Bonnie (ed.). Joan of Arc: Her Story. Translated by duQuesnay Adams, Jeremy. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-21442-5. OCLC 1035889959. [6] Gies, Frances (1981). Joan of Arc: The Legend and the Reality. Harper & Row. ISBN 0690019424. OCLC 1204328346. [7] Gies, Frances (1981). Joan of Arc: The Legend and the Reality. Harper & Row. ISBN 0690019424. OCLC 1204328346. Pernoud, Régine; Clin, Marie-Véronique (1999) [1986]. Wheeler, Bonnie (ed.). Joan of Arc: Her Story. Translated by duQuesnay Adams, Jeremy. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-21442-5. OCLC 1035889959. Sackville-West, Victoria (1936). Saint Joan of Arc. Athenium. OCLC 1151167808. [8] DeVries, Kelly (1999). Joan of Arc: A Military Leader. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-1805-3. OCLC 42957383. [9] Barker, Juliet (2009). Conquest: The English Kingdom of France, 1417-1450. Little, Brown. ISBN 9781408702468. OCLC 903613803. [10] Barker, Juliet (2009). Conquest: The English Kingdom of France, 1417-1450. Little, Brown. ISBN 9781408702468. OCLC 903613803. [11] DeVries, Kelly (1999). Joan of Arc: A Military Leader. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-1805-3. OCLC 42957383. [12] Hobbins, Daniel (2005). "Introduction". In Hobbins, Daniel (ed.). The Trial of Joan of Arc. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674038684. OCLC 1036902468. [13] Lowell, Francis Cabot (1896). Joan of Arc. Houghton Mifflin Co. OCLC 457671288. [14] Hotchkiss, Valerie R. (2000). Clothes Make the Man: Female Cross Dressing in Medieval Europe. Garland. ISBN 9780815337713. OCLC 980891132. [15] Gies, Frances (1981). Joan of Arc: The Legend and the Reality. Harper & Row. ISBN 0690019424. OCLC 1204328346. [16] Lucie-Smith, Edward (1976). Joan of Arc. Allen Lane. ISBN 0713908572. OCLC 1280740196.

The Writer’s Guide to Women in Single Combat

Posted on March 11, 2022 6 Comments

One of the most difficult positions a writer can put their female combatant is in a one-on-one fight or alone against multiple opponents. This is especially true if the attackers are bigger and stronger. Does that mean that a woman will lose every one of these fights? Absolutely not! There are women throughout history, including in our modern world, who can go toe-to-toe against a superior opponent and win.

As always, magic is the exception to the rule. Because magic.

Unevenly Matched

I covered several of the setbacks to female fighters in my previous article, The Writer’s Guide to Women in Combat, and offered some suggestions to overcome them. In this section, I will ignore the barriers created by culture, menstruation, and pregnancy and just focus on the physical challenges. Unless a female combatant is facing off against another woman or a weaker man, the odds are good that she will be outmatched. She will probably be at a disadvantage in several categories, including strength, height, and reach. This disparity increases with the number of opponents.

However, there are several areas a woman can focus on to give her an advantage. One of the biggest is skill. Most of the time, the more skilled fighter is the winner. This is true of both armed and unarmed combat.

Armed

One of the beautiful things about weapons is that they are force multipliers. This goes a long way in evening the playing field when fighting a physically stronger and taller opponent. She can gain an even greater advantage by carefully choosing her weapons. Shadiversity has a wonderful video here.

One of my favorite examples of a woman who excelled in dueling is Julie d’Aubigny. She was a 17th century French opera singer and fencer who wounded or killed at least ten men in duels. She was trained in fencing by her father, who taught the pages of King Louis XIV’s court. Also, one of her many lovers was an assistant fencing master with whom she toured France, performing singing acts and fencing exhibitions. She would often dress in men’s clothing and her fencing skills were so impressive that during one show, a drunk in the crowd loudly declared that she couldn’t be a woman. She dramatically tore off her shirt to prove him wrong. Another colorful story was when she attended a royal ball dressed in men’s clothing and spent most of the evening courting a young woman. Three of the lady’s suitors challenged her to duels when Julie publicly kissed her. She gladly accepted and won all three duels. I encourage you to read her full story because she had a wild life.

Unarmed

It is harder for a woman (or a weaker man) to win in unarmed combat against a superior opponent, but it isn’t impossible. Again, training and skill go a long way toward evening the odds. I know this from personal experience since I have a black belt in bujinkan ninjutsu. I have trained for years against bigger guys.

First, it’s learning the weak spots such as the elbows, knees, throat, and ears. A targeted attack against these areas can do a lot of damage without a lot of force. For example, it only takes seven pounds of pressure to break an elbow.

Second, it’s learning how to keep yourself safe. This is done by understanding the distance at which you are outside an opponent’s attacks. Of course, reach varies from person to person, but there is an average distance at which you are out of range, if just barely. One of the biggest lessons I have learned is taking advantage of the “corners.” Most attacks are circular. If you swing your arm or leg, you are tracing the edge of a circle. If you picture a circle inside a square, this means the corners of the square are outside the circle of attack, unless your opponent moves.

Another way to stay safe is to move off at an angle. Most people want to move forward while they attack. It is where they are strongest. However, if you back up at a 45° or 90° angle, your opponent must change direction, which dissipates their momentum and disrupts their flow.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2022 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

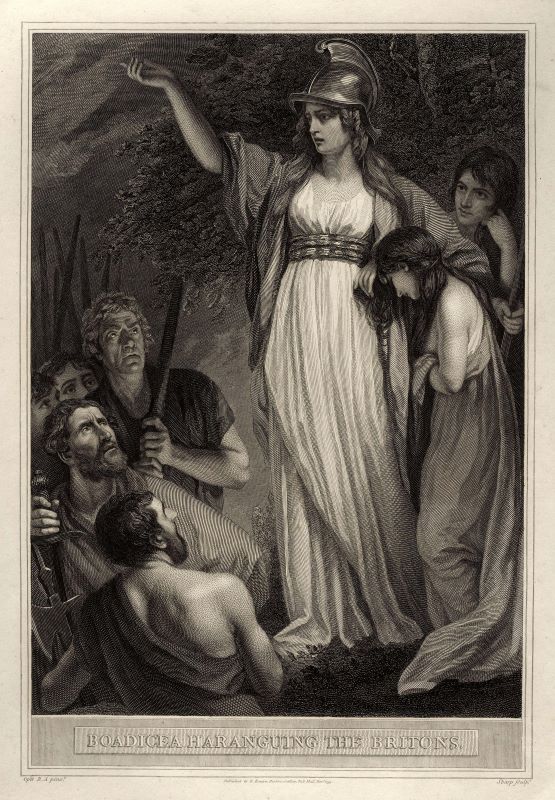

Writer’s Deep Dive: Boudica

Posted on March 4, 2022 1 Comment

One of the greatest tools and sources of inspiration that a writer has is history. The lives, actions, and motivations of historical people can be invaluable in shaping believable characters. As part of my series on female warriors, I will be sharing the stories of several formidable women. Today, we start with Boudica

Now, let’s dive in!

The Basics

Boudica (also known as Boadicea) was the wife of Prasutagus, who ruled the Iceni tribe in ancient Britain, in what is now Norfolk [1] The Romans had invaded in 43 AD and he had allied himself and his tribe with the invaders, hoping to preserve their independence. [2] When Prasutagus died in 60/61 AD, he tried to pacify the Romans further by leaving half of his fortune to the Emperor Nero, the other half going to his two daughters. [3] However, this wasn’t enough for the Romans. They sacked then confiscated much of the Iceni lands, pillaged the house of Prasutagus and Boudica, [4] claimed all the late king’s money, refused to acknowledge Boudica as her late husband’s heir, and demanded immediate repayment of money they had lent to him. [5] Not content with just this humiliation, the Romans flogged Boudica publicly and raped her daughters.

Boudica was determined that this humiliation had to be answered. She rallied the Iceni then gained the support of several neighboring tribes that already hated the Romans and were horrified at the abuse she and her daughters had suffered. She managed to raise an army 120,000 strong. [6]

Boudica and her army first marched on Camulodunum (modern Colchester) while the governor, Gaius Suetonius Paulinus, was away campaigning on the island of Mona (known today as Anglesey). [7] The city was a target of special hatred because they brutalized the neighboring Britons and built a lavish temple to Claudius. [8] Thankfully, the city was an easy target since the residents had dismantled much of the defenses to build houses and the Romans could only muster 200 soldiers, who were easily defeated. [9] There are no records of how involved Boudica and her daughters were in the fighting but she was definitely the one leading the army and her daughters were there.

Suetonius hurried back to the capital of Londinium (modern London) but when he saw Boudica’s army, he turned tail and ran. Boudica’s army captured the city, burned it down, and slaughtered everyone they found. They then moved on to the city of Verulamium (known today as St. Albans), which they captured and destroyed. [10]

Suetonius regrouped, amassing an army of 10,000 men. [11] He took up position on defensible ground and waited for Boudica to come to him. Even though the rebel army now numbered between 230,000 to 300,000 warriors they were defeated by the superior training, tactics, and equipment of the Roman forces. According to the historian, Tacitus, the Romans were so hateful that they slaughtered the women and animals. [12] There are conflicting stories of Boudica’s fate. Historians have claimed that she poisoned herself, was killed in battle, or died of a sickness. There are no records of what became of her daughters.

The Write Angle

For authors writing women warriors, especially those leading armies, Boudica can offer a huge amount of inspiration and insight. She was skilled at rallying fighters to her cause and played up the abuse leveled against her and her daughters to enrage people and stoke the hatred they already had toward the Romans. She was knowledgeable about the land and the weak locations that were the best targets.

Her army was incredibly brutal and did torturous things to people whose only crime was living in a Roman city. I have not gone into detail because of the horrific nature of the subject; you are welcome to research it yourself if you like.

In the end, Boudica’s pride was her downfall. She came to underestimate her enemy. She won three decisive victories against Roman cities and had come to believe that her superior numbers would overcome any advantage the Romans possessed. Her enemy was able to regroup and employ tactics that had been successful in the past, including against overwhelming odds. Ultimately, they used her hubris and hatred against her.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2022 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Hingley & Unwin (2006). Boudica: Iron Age Warrior Queen. London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. p. 197. [2] Hingley & Unwin (2006). Boudica: Iron Age Warrior Queen. London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. pp. 19, 23. [3] Newark, Timothy (1989). Women Warlords: An Illustrated Military History of Female Warriors. London: Blandford. p. 85. [4] Tacitus, The Annals, 14.31 [5] Cassius Dio, Roman History, 62.2 [6] Hingley & Unwin (2006). Boudica: Iron Age Warrior Queen. London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. p. 70. [7] Hingley & Unwin (2006). Boudica: Iron Age Warrior Queen. London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. p. 44. [8] Hingley & Unwin (2006). Boudica: Iron Age Warrior Queen. London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. p. 71. [9] Webster, Graham (1978). Boudica, the British Revolt against Rome Ad 60. Totowa: Rowman and Littlefield. p. 90. [10] Hingley & Unwin 2004, p. 180 [11] Tacitus, Annals 14.34 [12] Tacitus, Publius, Cornelius, The Annals, Book 14, Chapter 35

The Writer’s Guide to Women in Combat

Posted on February 25, 2022 3 Comments

Writers have had a fascination with women warriors for centuries. The ancient Greeks wrote about the Amazons, a fierce tribe of female fighters. The main event in many Roman gladiatorial games were the gladiatrices, female gladiators. In our modern stories, we have quite the league of combat heroines, such as Eowyn, Arya, Katniss, and Wonder Woman.

Yet there has been criticism of depictions of women in combat. Today, I will cover the challenges of writing female fighters, especially in historical settings, and ways to sidestep them. Over the next weeks, I will explore women in single combat and on the battlefield, as well as highlighting several female warriors.

As always, magic is the exception to the rule. Because magic.

Why Are Women Warriors Rare in History?

When we look to history, the ranks of female fighters are thin. There were several factors that either discouraged women from fighting or likely caused military commanders to exclude them.

Cultural

Many world cultures strongly encouraged women to focus on marriage and child rearing. Often, this was necessary to ensure the survival of the group. If too many women die in combat, there are fewer children born. If the birth rates drop too low, the group will eventually die out. Populations can absorb the death of a significant number of men more easily than the death of a large group of women. This is because of the ability of one man to impregnate multiple women, leading to the birth of several children. This reasoning is why hunting and fishing targets the males of a species, to ensure its continuation. Due to this biological fact, many world cultures have cemented the expectations for women to be that of wife and mother.

There are some cultures that are more accepting of female fighters, such as the Vikings. Often these cultures exist in harsh environments and need “all hands on deck” to survive. They are often egalitarian in other areas of their culture and commonly give women more rights and freedoms than other restrictive societies.

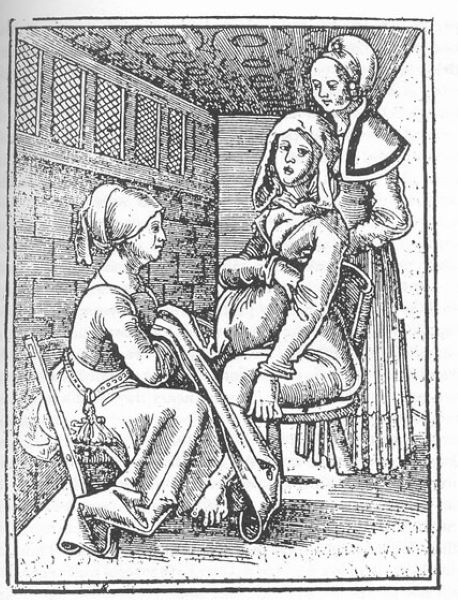

Menstrual Cycles, Pregnancy, and Childbirth

A woman’s menstrual cycle could limit her effectiveness in combat, especially if she is experiencing pain. Of course, not all women are debilitated during menstruation. There are female athletes who have won gold medals during their cycles.

Another challenge is pregnancy. If an army is a mixture of men and women, even if they are segregated into different units, there will probably be sexual activity. When putting young healthy people together, it’s almost inevitable. Obviously, being pregnant, especially in the second and third trimester, makes a soldier unfit for combat. Not that a heavily pregnant woman could not fight, but it would endanger the success of a military engagement and a commander would probably be reluctant to use pregnant soldiers or those that could become pregnant.

There is also the danger of dying in childbirth, which was unfortunately all too common during much of human history. The possibility of losing a soldier that you have invested time in training would give many military commanders pause.

Physical Ability

A biological reality is that the average woman is physically weaker than the average man, with 5-50% less upper body strength. [2] Women’s bones are less dense, making them more likely to break [3] However, athletic records show that most women have more endurance than men. So, female soldiers could be better than long marches than their male counterparts, but would likely be at a disadvantage in physically taxing combat. Of course, there are several other factors at play, such as weapons used, training, skill, size, reach, and luck. In fact, we know of several women in history who were deadly swordsmen.

Overcoming These Challenges

As writers, we have several ways to overcome the challenges faced by our badass female protagonists. This is especially true if magic and technology are in the mix.

Menstrual pain could be minimized or eliminated with a spell or an herb. There are several real-world plants that minimize cramping such as ginger, nettle, fennel, and raspberry leaf. Pregnancy can be prevented the same way, with magic or herbology. In fact, the ancient Romans had a plant, silphium, that acted as effective natural birth control. Unfortunately, it is now extinct. [1]

A weaker character can be strengthened using magic or technology, like a power suit. Also, female fighters can focus on ranged attacks, such as archery.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2022 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Did the ancient Romans use a natural herb for birth control?, The Straight Dope, October 13, 2006 [2] "Women in Combat: Frequently Asked Questions". Center for Military Readiness. 22 November 2004. Archived from the original on 20 December 2004. [3] "Effect of Isokinetic Strength Training and Deconditioning on Bone Stiffness, Bone Density and Bone Turnover in Military-Aged Women". Archived from the original on 2013-06-26. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

Writer’s Deep Dive: Horse Bits

Posted on February 18, 2022 1 Comment

Most people know that the primary way that a horse is steered is by using a bit. However, there is a lot more to it.

Now, let’s dive in!

The Basics

First, the bit is not the only way a rider communicates with their horse. Weight shifts, leg cues, verbal commands, and sometimes whip cues are all used with the reins and bit.

Before we get too far into the subject of bits, there is sometimes you need to understand about horse’s mouths. Horses have two sets of teeth: incisors and molars. The incisors are the front teeth that are used for cutting grass when a horse is grazing, although they can also be used for defense or attack. The molars are the large flat-topped grinding teeth that chew the grass before it’s swallowed. Unlike our teeth, horses have a gap between the two where there are only gums. It is in this gap that the bit sits. It is not resting on the teeth themselves.

Occasionally, horse will have wolf teeth that grow in that gap between the incisors and molars. It can be painful for the horse to have a bit hit their wolf teeth. Nowadays, wolf teeth are commonly removed surgically. The corner of a horse’s mouth lines up with the gap between the incisors and molars, which is known as the interdental space.

The bit applies pressure to the tongue, gums, and sometimes the roof of the mouth. If the bridle is too loose, the bit will bang against the back incisors. If it’s too tight, it will press against the front molars. The horse can become desensitized, which is known as “hard mouthed” if a rider is too harsh with the bit.

There is some specific terminology when discussing bits.

Bar or Mouthpiece – The piece that sits across the horse’s tongue and gums. It can be a solid piece of metal or twisted wire and can be straight, jointed or curved. It’s believed that thicker bits are gentler while thinner bits are harsher.

Cheekpieces – The cheekpieces connect to the bar at either side outside the horse’s mouth. The rest of the bridle is attached to the top of the cheekpieces, while the reins are attached to the bottom. There are several styles of cheekpieces, including D-ring and eggbutt.

Shanks – Shanks are pieces that extend downward from the cheekpieces. When the reins are pulled, they rotate the bit in the mouth and apply leverage. The longer the shanks, the stronger the leverage and the less pressure is needed on the reins to create it.

The Write Angle

Proper fitting of the bit and handling of the reins can be a way for a writer to point out that a character knows what they are doing with horses. Also, one trick to get a horse to open its mouth for the bit is to put your thumb in the gap and wiggle it around. Most horses open their mouths and you’re in no danger of being bit. Show instead of tell, right?

It is possible for a horse to get the bit between their teeth and take control away from the rider. This is an opportunity for some moments of drama or tension, especially if it involves a runaway horse with the rider hanging on for dear life.

If a character is tacking a green horse, you can point out that they are choosing a gentle bit with a thick bar and no shanks. In converse, a character could be forced to choose a thin bit with long shanks to control an unruly hard-mouthed horse.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2022 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

The Writer’s Guide to Ecclesiastical Titles

Posted on February 11, 2022 6 Comments

Besides royalty and nobility, members of the clergy also have a rich history of titles and forms of address. Since religion, especially Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy, played such a large part in European society throughout much of history, it is important for a writer who is setting their story in this period or one drawing inspiration from it to know the basics of church hierarchy and forms of address.

If you need the titles and forms of address for royalty and nobility, please read my previous articles here and here.

If you are writing fantasy, they can be discarded completely in favor of your own inventions, if you so wish.

Pope and Patriarch

The pope is the head of the Roman Catholic Church and the patriarch is the leader of the Eastern Orthodox church.

The most common form of address for the pope is “your Holiness.” This title can also be used when referencing him, e.g., “his Holiness” or “His Holiness Pope Francis.” The term “Holy Father” is also used as well as “Most Blessed Father” and “Most Holy Father.” During the Middle Ages, the term “Dominus Apostolicus,” meaning “the Apostolic Lord,” was used. [1] Other titles have been applied to the pope, including Bishop of Rome, Vicar of Jesus Christ, Successor of Peter, and many more. [2]

The Ecumenical Patriarch of the Eastern Orthodox church is addressed as “Your All-Holiness” and referred to as “His All-Holiness.” The formal form of address is “Bartholomew, by the grace of God Archbishop of Constantinople, New Rome and Ecumenical Patriarch.” [3]

Cardinal

A cardinal oversees a large territory and directs the archbishops and bishops that report to him. Collectively, they make up the college of cardinals. One of their responsibilities is selecting the next pope after the previous one dies or retires. In the Catholic church, they are well known for their red vestments.

They are commonly addressed as “Your Eminence” and referred to as “His Eminence.” They are considered princes of the church and can be addressed in the same way with “Your Grace.” [4]

Archbishop

An archbishop leads an archdiocese, a large or heavily populated area that included all the churches located inside its boundaries.

They are addressed as “Your Excellency” and referred to as “His Grace Archbishop (Name).” Other common forms of address include “Your Grace” with the title being “The Most Reverend.”

Eastern Orthodox archbishops are referred to as “The Most Reverend Archbishop (Name) of (Place)” and addressed as either “Your Beatitude” or “Your Eminence.” [5]

Bishop

A bishop oversees one or more dioceses and is under the authority of their archbishop.

The common form of address in the Roman Catholic church is “Your Grace.” He is referred to as “Bishop (Name).”

Bishops in the Eastern Orthodox church as referred to as “The Most Reverend Bishop (Name) of (Place)” and addressed as “Bishop (Name).”

Priest

A priest handles a parish church.

His is usually addressed and referred to as “Father (Name)” or just “Father.” An Eastern Orthodox priest is also called “Father” but can additionally be referred to as “The Reverend Father.” [4]

Religious Orders

In both the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches, there are religious orders whose members are referred to as monks, if male, and nuns, if female. In the Catholic tradition, they are called “Brother (Name)” and addressed as “sister” or “Sister (Name). It’s the same in the Eastern Orthodox tradition, although monks are referred to as “Father” and nuns as “Mother” or “Sister.”

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2022 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Guruge, Anura (2008). Popes and the Tale of Their Names. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4343-8440-9. [2] Annuario Pontificio, published annually by Libreria Editrice Vaticana, p. 23*. ISBN of the 2012 edition: 978-88-209-8722-0. [3] Rodopoulos, Panteleimon (2007). "Institutions of the Ecumenical Patriarchate". An overview of Orthodox canon law. Translated by Lillie, W.J. Rollinsford, N.H.: Orthodox Research Institute. p. 213. ISBN 1-933275-15-4. OCLC 174964244. [4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_religious_titles_and_styles#Catholicism [5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archbishop

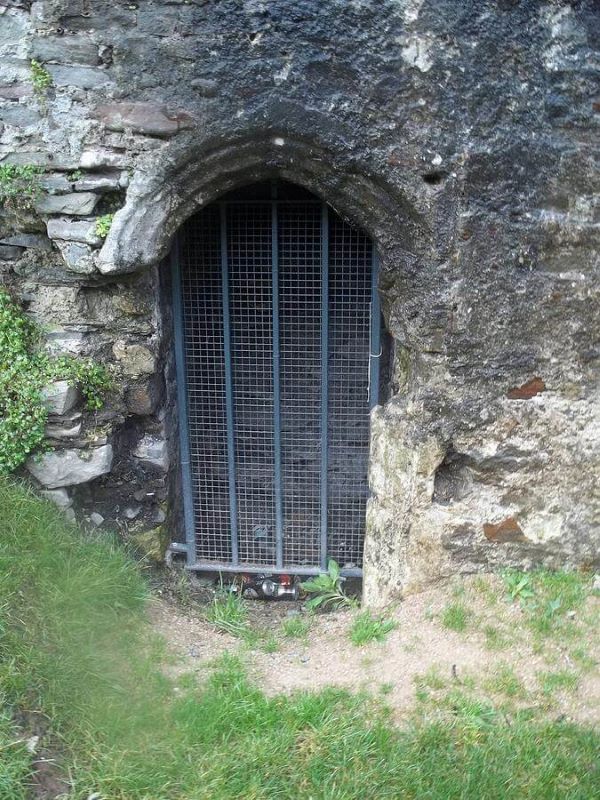

Writer’s Deep Dive: Posterns

Posted on February 4, 2022 7 Comments

Castles and fortified cities are popular with writers. Access to them can become critical to the plot, especially during a war or siege. Gates and barbicans are well-known access points, but many castles and cities use posterns as a secondary point of entrance or exit. Let’s dive in!

The Basics

Posterns, also known as sally ports, were secondary doors or gates. They were set into the outer curtain wall of a castle or city. They were usually small, with only enough room for one person to pass through at a time, although some were large enough for a horse and rider. Often, they were concealed, making it difficult or impossible for someone unfamiliar with their location to find them. They commonly had gates or doors that locked or latched shut.

Because of their size, they were easier to defend, since only one soldier or rider could come through at a time. This created a chokepoint that favored the defenders. [1]

Posterns had a varied of uses, including as a sally port during a siege to attack the besieging army, a discrete way of entering or exiting, and an escape route.

There are historical records of posterns and several that still exist. The cities of Jerusalem, London, and York had many posterns. Posterns are also mentioned in literature. In Le Chanson de Girart de Roussillon, the hero escapes through a postern when he is betrayed. In Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, a knight of the Round Table flees through a postern. [2]

The Write Angle

There are so many opportunities for a writer when it comes to posterns.

If you have a character that needs to escape from a castle or walled city, a postern provides a great option. Since some of them were large enough for a horse and rider, messengers could use them to escape a besieging army, especially since posterns were well away from the main gates and commonly concealed. In fact, in my in-process novel, I use a postern as a means of escape for several messengers fleeing a besieged city.

A postern could also be used to get into a castle or walled city. If a person is told of the location of a concealed postern, they could sneak in. The door could be opened from the inside or the lock could be picked from outside. It could also be used by a resident of a castle or walled city to sneak out to meet a sweetheart or deliver covert information.

Of course, as I mentioned above, posterns were used by soldiers to sneak out and launch surprise attacks on an enemy army, especially if they are besieging the castle or city. A castle’s soldiers could also sneak into an enemy’s encampment and sabotage their tools and equipment, turn their horses or other livestock loose, or set things on fire.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2022 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

[1] Van Emden, Wolgang. "Castle in Medieval French Literature", The Medieval Castle: Romance and Reality (Kathryn L. Reyerson, Faye Powe, eds.) U of Minnesota Press, 1991, p.17 ISBN 9780816620036 [2] Malory, Thomas. Le Morte D'Arthur, Chap IV, Library of Alexandria, 1904