The Writer’s Guide to Burns

Posted on May 9, 2025 Leave a Comment

Burns are some of the most painful and visually striking injuries a character can endure. Whether caused by fire, chemicals, or magic, burns add tension, vulnerability, and long-term consequences to a story. Writing them realistically requires an understanding of their degrees, symptoms, appearance, treatment, and long-term effects.

This guide will help you craft authentic, impactful burn injuries that enhance your storytelling while respecting the severity of these wounds.

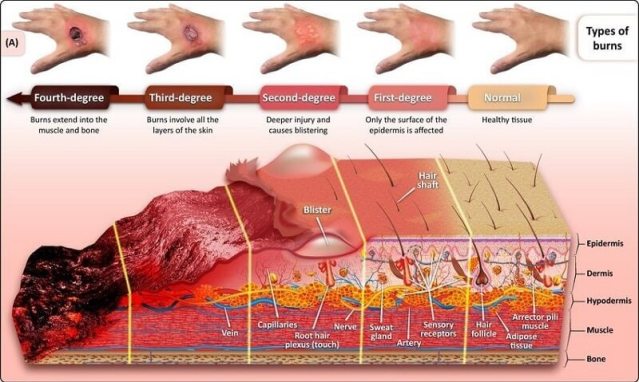

Degrees of Burns

Burns are categorized by degree based on depth and severity. Each type presents different challenges and healing processes.

First-Degree Burns (Superficial Burns)

Depth: Affects only the epidermis (outer skin layer).

Appearance: Red, dry skin with mild swelling. No blisters.

Symptoms: Pain, minor discomfort, slight warmth.

Healing Time: Heals within 3–7 days without scarring.

Second-Degree Burns (Partial-Thickness Burns)

Depth: Affects both the epidermis and dermis (deeper skin layer).

Appearance: Red, blistered skin that may be wet or weeping.

Symptoms: Severe pain, swelling, increased sensitivity.

Healing Time: Heals within 2–3 weeks, often with scarring.

Third-Degree Burns (Full-Thickness Burns)

Depth: Destroys the epidermis, dermis, and may reach fat, muscle, or bone.

Appearance: Waxy, white, leathery, or charred black skin.

Symptoms: No immediate pain (nerves are destroyed), but surrounding tissue may be excruciatingly painful.

Healing Time: Months, often requiring skin grafts and leaving permanent scarring.

Fourth-Degree Burns and Beyond

Depth: Extends through muscle, tendons, and bone.

Appearance: Charred, blackened tissue; often results in limb loss.

Symptoms: No pain in the burned area, but intense pain in adjacent, still-living tissue.

Outcome: Often fatal or results in amputation.

Common Causes of Burns in Fiction

Your setting and story’s world-building will dictate how burns happen here are some examples.

Fire or Flames: House fires, explosions, magic spells, dragon breath.

Scalding Liquids or Steam: Boiling water, molten metal, volcanic steam.

Electrical Burns: Lightning strikes, malfunctioning technology, energy weapons.

Chemical Burns: Acid attacks, industrial spills, alchemical accidents.

Friction Burns: Rope burns, high-speed crashes, skidding on rough terrain.

Radiation Burns: Sunburn, nuclear exposure, laser weapons.

Example: “The alchemist screamed as the bubbling potion splashed onto her wrist. The liquid ate through her sleeve, and the burning sensation intensified as her skin blistered beneath it.”

How Burns Affect the Body and Mind

Burns aren’t just painful—they’re debilitating, both physically and emotionally. Consider these effects in your writing.

Immediate Physical Reactions

Pain: Ranges from stinging (first-degree) to unbearable agony (second-degree) to eerie numbness (third-degree).

Shock: Severe burns can cause shock, leading to dizziness, confusion, or fainting.

Adrenaline: Characters may not initially feel pain due to adrenaline, but it will hit once the rush fades.

Example: “She barely noticed the fire’s bite at first, her mind focused on escaping. It wasn’t until she reached safety that the agony hit, making her gasp and clutch her seared skin.”

Long-Term Effects of Burns

Burns leave permanent reminders of trauma. Their consequences shape a character’s future physically and psychologically.

Scarring and Disfigurement: Severe burns cause thick, raised scars (keloids) or contractures that limit movement.

Chronic Pain and Sensitivity: Nerve damage can lead to either numbness or hypersensitivity in burned areas.

Psychological Trauma: PTSD from the injury (flashbacks, nightmares, fear of fire). Self-esteem issues from disfigurement.

Loss of Functionality: Stiffness, nerve damage, or amputations affecting mobility and dexterity.

Example: “His hands, once quick and steady, trembled as he struggled to grasp the pen. The scar tissue pulled against his knuckles, a cruel reminder that he’d never forge another blade again.”

Using Burns in Storytelling

Symbolism: A burn scar could serve as a reminder of past trauma, a mark of survival, or a curse from an enemy.

Challenges and Growth: A warrior with severe burns might struggle to wield a sword again, forcing them to adapt their fighting style.

Tension and Stakes: A character suffering a serious burn mid-mission may slow the group down, forcing difficult decisions.

Depicting Burns Across Genres

Burns are devastating injuries that can add drama, stakes, and lasting consequences to a story. However, how burns are received, described, and treated varies depending on the genre. Elements such as armor in fantasy or advanced medicine in science fiction will affect the realism and severity of burn injuries.

Contemporary

In a modern setting, burns are medical emergencies, and their portrayal should reflect real-world causes, treatments, and psychological effects.

Common Causes

House Fires: Accidental or arson-related.

Electrical Accidents: Exposed wires, lightning strikes.

Car Accidents and Explosions: Gasoline fires, airbag friction burns.

Chemical Exposure: Industrial spills, acid attacks.

Radiation Burns: Sunburns, workplace hazards, or medical treatment side effects.

Typical Treatments

First-Degree Burns: Cold compresses (but no ice, as it damages tissue). Aloe vera, over-the-counter creams, and pain relievers.

Second-Degree Burns: Cleaning the wound with sterile water. Applying antibiotic ointments (like Silver Sulfadiazine). Dressing the wound with non-stick bandages.

Third and Fourth-Degree Burns: Transplanting healthy skin to cover the wound. IV fluids and pain management to prevent dehydration and shock. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy speeds up healing and reduces tissue damage. Physical therapy to restore mobility in affected areas.

Challenges

Long Recovery Time: Severe burns require months or years of healing.

Psychological Trauma: Many burn survivors suffer from PTSD, depression, or body-image struggles.

Impact on Characters

Medical Response: Characters with serious burns will require hospitalization, skin grafts, and physical therapy.

Psychological Trauma: Fire-related PTSD or pyrophobia (fear of fire). Body image struggles from disfigurement and scarring.

Legal and Social Consequences: Arson-related burns might bring police investigations. Chemical burns could spark lawsuits or revenge plots.

Example: “The fire was out, but her world still burned. The skin on her arm felt too tight, too raw beneath the bandages. She traced the edge of the scar, wondering how long it would take before she stopped flinching at her own reflection.”

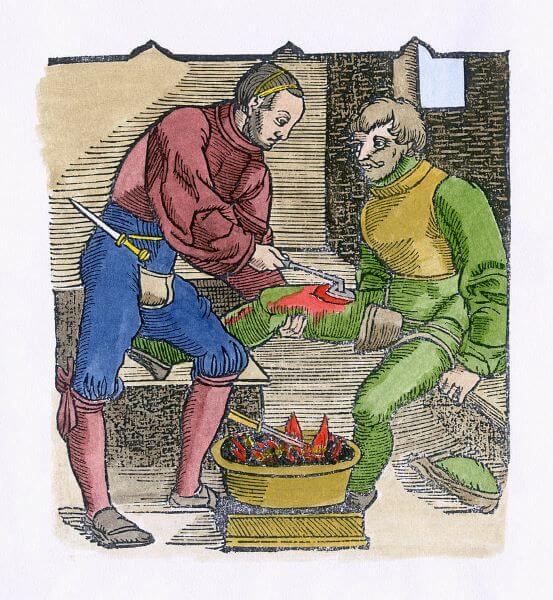

Historical

In historical fiction, burns are more dangerous due to rudimentary medical care, lack of hygiene, and limited understanding of infections. Burns that might be treatable today could be fatal in the past.

Common Causes

Cooking and Hearth Accidents: Open fires, boiling liquids.

Weaponry: Flaming arrows, Greek fire, gunpowder explosions.

Punishments: Branding, torture, or execution by fire.

Occupational Hazards: Blacksmithing, glassblowing, working in forges.

Ancient World Treatments

Honey: Used as an antiseptic to prevent infection and aid healing.

Milk, Vinegar, or Wine: Used as cooling agents to wash burns.

Animal Fats and Oils: Applied to burned skin, though this often trapped heat and worsened the injury.

Herbal Poultices: Aloe vera, myrrh, and resin-based salves provided some relief.

Religious or Superstitious Practices: Prayers, charms, or ritualistic cleansing were used in many cultures.

Medieval World Treatments

Cold Water and Herbal Pastes: Comfrey, chamomile, and lavender were used to soothe burns.

Goose Fat and Lard: Applied to burned skin, but often worsened infections.

Poultices with Honey and Egg Whites: Thought to reduce inflammation and aid healing.

Bloodletting and Humoral Theory: Some physicians believed burns were caused by an imbalance of humors and prescribed bloodletting.

Cauterization (For Severe Burns): Some burns were intentionally burned again with hot iron to prevent infection, though this often made things worse.

Challenges

Lack of Sterile Conditions: Treatments were performed with dirty hands and tools, increasing the risk of gangrene or tetanus.

Severe Burns Were Fatal: Without skin grafting or antibiotics, third-degree burns were often deadly.

Impact on Characters

Risk of Infection: Without antibiotics, burns could lead to sepsis or gangrene.

Superstitions: Superstitions about fire curses or divine punishment.

Social Stigma: Burned individuals might be seen as “touched by fire” or marked by the gods. A visible burn might impact marriageability or social standing.

Example: “The blacksmith’s apprentice hissed as the molten metal licked his wrist. The master barely spared him a glance. ‘Rub some lard on it, boy. It’ll heal soon enough.’ But the angry red mark told a different story—it would scar.”

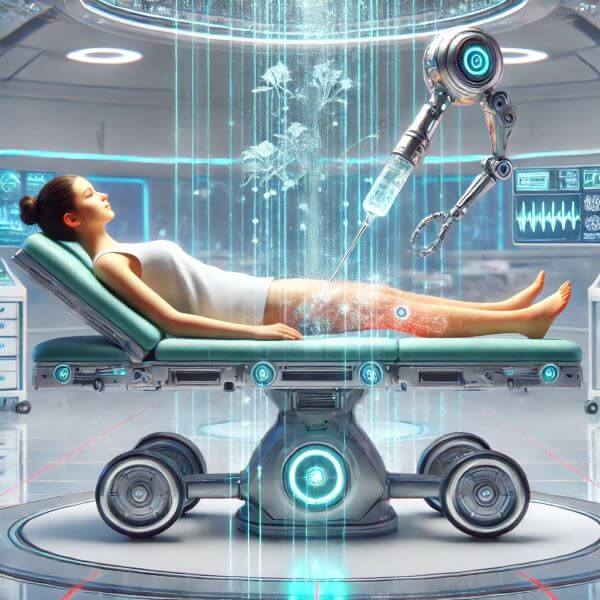

Science Fiction

In sci-fi, burns might result from high-tech weaponry, energy fields, or alien environments, and treatment options may be far beyond modern medicine.

Common Causes

Laser and Plasma Weapons: Clean entry burns with cauterized wounds. Plasma burns might leave molecular scarring.

Radiation and Cosmic Burns: Space travel exposure leading to slow, cellular burns. Biohazard contamination causing genetic mutations.

Cybernetic Malfunctions: Overheating implants causing internal burns. Acidic nanotech failures corroding tissue.

Treatment

Regenerative Gels: Special biotech creams that instantly regrow skin cells. Medicated sprays that seal wounds and prevent infection.

Nanobot Therapy: Tiny robotic cells that reconstruct burned tissue at a molecular level. There may be a risk of the nanites malfunctioning, causing uncontrolled mutations.

Synthetic Skin Grafts: Lab-grown tissue that perfectly replaces burned skin. Biotech armor layers that integrate with the nervous system.

Cybernetic Replacements: Severe burns might lead to cybernetic limb replacements. A character’s synthetic skin could change color or texture over time.

Challenges

Is Regeneration Painful? Would regrowing skin feel like being burned again?

Side Effects? Does nanotech healing cause loss of sensation or genetic changes?

Availability? Are advanced treatments only for the rich, or is healing universal?

Tactical Considerations

Energy Shields: Prevent burns but might overload, causing internal damage.

Zero-Gravity Burns: Fire behaves differently in space, potentially causing oxygen-starved slow burns.

Example: “The laser grazed his shoulder, leaving a seared wound with clean, blackened edges. The med-bot injected regenerative nanites, but the process burned from the inside out, reshaping his flesh at a molecular level.”

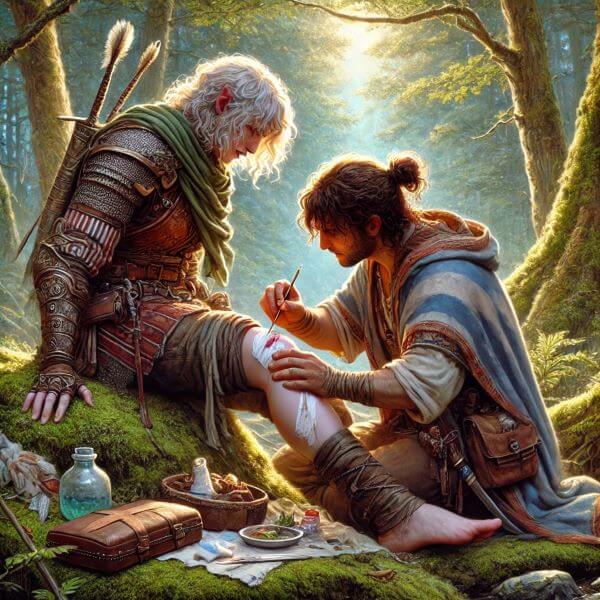

In fantasy settings, burns might be caused by magic, alchemy, enchanted weapons, or mythical creatures, leading to unnatural healing processes or permanent magical effects.

Common Causes

Fire-Based Magic: Spellcasters wielding flames or pyromantic attacks.

Dragon Fire or Elemental Damage: Burns caused by creatures or curses.

Enchanted Weapons: Swords that leave scorch marks instead of cuts.

Alchemical Accidents: Potions gone wrong or magical explosions.

Holy or Cursed Fire: Divine punishment or unholy flames that never heal.

Treatments

Healing Magic: Instantaneous healing, but at a cost (e.g., exhaustion, memory loss, or magical scars). Healing spells that regrow tissue but leave magical side effects (e.g., glowing scars).

Alchemical Salves: Potions that soothe burns but must be applied before the wound turns necrotic. Rare herbs that neutralize magical burns but require difficult-to-obtain ingredients.

Holy Blessings or Curses: A priest’s touch might purge infection but leave permanent disfigurement as penance. Burns caused by divine fire might never heal naturally.

Challenges

Do Magic Burns Heal Differently? If a fire spell causes burns, can it be healed like normal burns, or does it require specific counter-magic?

Do Healing Spells Have Limits? Does healing require rare ingredients, a price, or time to work?

Permanent Consequences? Does regenerated skin feel different? Does magic prevent scarring, or do healed characters still bear marks of past injuries?

Impact on Characters

Armor Protection: Metal armor heats up and scalds the wearer if exposed to flames. Leather armor burns but offers slight protection. Magical barriers might negate fire but leave residual energy burns.

Magic’s Role in Healing

Instant Healing? Does a healer’s magic fully restore the skin, or does it leave scars?

Side Effects: Magical burns might cause painful visions, mutations, or permanent runes.

Legendary Scars: Fire-wielders might bear permanent scorch marks on their skin. A chosen one’s burn could be a divine mark.

Example: “The flames licked at her arm, but it was no ordinary fire. The spell had branded her flesh with glowing runes that pulsed under her skin. She knew, with a sinking dread, that no healer could undo what magic had wrought.”

Plot and Character Ideas

Burns are more than just physical injuries—they can shape characters, drive plots, and create lasting consequences. In fantasy and science fiction, burns can take on magical, alien, or technological properties, adding unique complications to a character’s journey. Below are plot and character ideas centered around burns, with genre-specific twists for fantasy and sci-fi—especially for non-human characters with different physiologies.

The Fire-Touched Prodigy

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A young mage accidentally burns themselves while attempting to control fire magic. The burn does not heal naturally but instead begins to glow with latent power, marking them as a potential chosen one—or a cursed outcast.

Character Angle: The burn may unleash hidden magical potential but also cause unbearable pain. The character struggles to control their magic while hiding the mark from those who might seek to exploit it. Healing magic fails to repair the wound, forcing them on a quest to find an ancient cure.

Example: “The flames licked at her skin, but instead of searing pain, she felt something else—power. When the fire died, the burn on her palm pulsed with golden light, whispering secrets only she could hear.”

The Cybernetic Burn Survivor

Genre: Science Fiction

Plot Idea: A character suffers third-degree burns in a lab accident or battle and undergoes experimental treatment that replaces their burned skin with synthetic bio-tech armor. However, the graft begins to malfunction or evolve, changing their identity and sense of self.

Character Angle: They struggle to adjust to their new cybernetic enhancements, questioning if they are still fully human. The cybernetic skin may grant superhuman abilities (strength, sensory perception) but come with unintended side effects, such as pain or alien thoughts. They must track down the scientist who performed the experiment before the graft completely overrides their biological self.

Example: “The synthetic graft pulsed under his skin, responding to his emotions. He clenched his fist, watching as the burnt remnants of his former self shifted, his hand morphing into something stronger—and less human.”

The Phoenix’s Curse

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A warrior is burned to the brink of death in battle but is resurrected by a phoenix’s flames. While they survive, their wounds never stop simmering with heat, and every time they take damage, the burns flare back to life.

Character Angle: The character must constantly endure pain, knowing they can never fully heal. They seek a way to break the phoenix’s curse, even if it means dying permanently. Fire no longer harms them, but water scalds them like acid, making them vulnerable in unexpected ways.

Example: The first time the flames consumed him, she thought he was dying. The second time, she realized the fire was inside her now, waiting for its next chance to rise.”

The Alien Who Burns Differently

Genre: Science Fiction

Plot Idea: An alien character suffers burns but, due to their unique physiology, their wounds react differently—perhaps their scars crystallize, their skin regenerates with a new texture, or their burns emit light or sound.

Character Angle: The injury makes them stand out among their own species, making them an outcast. The burn mutates their DNA, giving them abilities or revealing ancient biological secrets. The character must understand the science of their injury before it spreads or kills them.

Example: “The plasma bolt grazed her shoulder, and instead of scarring, the wound hardened into a lattice of glowing blue crystal. ‘I don’t think this is healing,’ she whispered. ‘I think I’m changing.’”

The Alchemist’s Catastrophe

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A brilliant but reckless alchemist attempts to craft an elixir of fire resistance but miscalculates, resulting in an explosion that burns away half their body. The injury is no ordinary burn—it continues to smolder indefinitely.

Character Angle: The burn acts as a gateway to a fire realm, allowing them to tap into elemental power, but at great cost. Every time they use their newfound abilities, the burns spread and worsen, threatening to consume them. They must find a mythical ingredient to neutralize the reaction before their entire body turns to ash.

Example: “The fire didn’t stop burning. It smoldered beneath his skin, flickering along his veins like candlelight. He had created something unnatural, and now he would have to live with it.”

The Soldier with Synthetic Skin

Genre: Science Fiction

Plot Idea: A genetically enhanced soldier is burned in combat, and instead of traditional treatment, their military implants trigger rapid regeneration—but the new skin is translucent, bio-luminescent, or reactive to touch.

Character Angle: The soldier struggles with alienation, as their wounds mark them as inhuman among their peers. The burns may allow stealth abilities (chameleon-like blending) but cause extreme pain when activated. They discover the experiment was intentional, and they must decide whether to embrace or destroy the technology.

Example: “He touched his face, expecting to feel ruined flesh. Instead, his fingers met smooth, glass-like skin. It pulsed faintly, responding to his breath. Whatever they had done to him, he wasn’t just human anymore.”

The Flamebound Knight

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A warrior swears an oath to wield a sword forged in divine flame, but the blade brands their hands and arms with perpetual burns. The longer they use the weapon, the more the fire consumes them.

Character Angle: The knight is torn between duty and self-preservation—if they abandon the sword, their burns might heal, but at what cost? The burns give them supernatural strength, but using it shortens their lifespan. They search for a way to temper the flames, hoping to balance power and survival.

Example: “The sword’s hilt seared against her palm, yet she did not let go. Pain was the price of power, and as long as she could wield it, she would endure.”

The Healer Who Can’t Heal Themselves

Genre: Fantasy or Science Fiction

Plot Idea: A gifted medic or magical healer can cure others of burns effortlessly—but any injury they receive is permanent. When they suffer severe burns, they must rely on others to save them for the first time.

Character Angle: Used to healing others, they must confront their own vulnerability. Their burns act as a permanent reminder of their limitations. They must seek a cure beyond their own knowledge, forcing them into an unfamiliar world of science or magic.

Example: “She had saved thousands, yet no magic could mend her own wounds. The fire had stolen her hands, and now, she could heal no one.”

Burn injuries in fiction add emotional weight, physical struggle, and long-term challenges. By understanding their degrees, symptoms, treatments, and psychological impact, you can write burns realistically and powerfully. Whether your character wields fire, survives an explosion, or suffers a magical curse, burns can leave scars—both visible and unseen—that shape their journey.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

The Writer’s Guide to Bruises

Posted on April 25, 2025 1 Comment

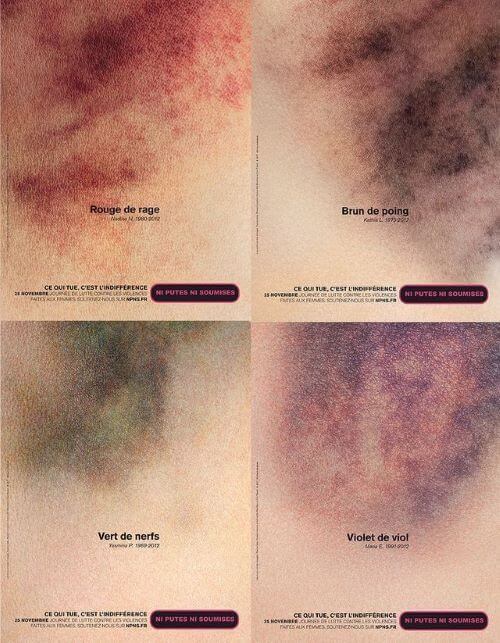

Bruises, also known as contusions, may seem like minor injuries compared to fractures or puncture wounds, but they can add realism and depth to your storytelling. Whether they’re caused by a fall, a punch, or a supernatural event, bruises can serve as visible reminders of a character’s struggles. Writing them realistically involves understanding their types, symptoms, severity, appearance, and recovery process, as well as potential long-term effects.

In this article we will discuss portraying bruises authentically, from the science behind their formation to their role in character development.

What Are Bruises and Contusions?

A bruise or contusion occurs when small blood vessels (capillaries) under the skin are damaged due to blunt trauma, causing blood to leak into the surrounding tissues.

Types of Bruises

Subcutaneous Bruises: Just beneath the skin. Commonly caused by minor bumps or impacts.

Intramuscular Bruises: Deeper bruises affecting the muscle tissue. Caused by harder impacts or repetitive strain.

Periosteal Bruises: Involve the bone surface (bone bruise). Extremely painful and often result from severe impacts like falls or direct blows.

Choose the type of bruise based on the severity of the event in your story. A simple stumble might cause a subcutaneous bruise, while a sword blow could lead to a periosteal bruise.

Symptoms of Bruises

The symptoms of a bruise depend on its depth and severity. Use these details to show your character’s discomfort and limitations.

Pain: Mild for subcutaneous bruises, sharp or throbbing for deeper contusions.

Swelling: Caused by inflammation around the injured area.

Skin Discoloration: The hallmark of a bruise, starting red or purple and changing colors over time.

Stiffness and Limited Mobility: Common with muscle or bone bruises, especially near joints.

Example: “Her arm throbbed where the bandit’s club had struck, the skin already turning an angry purple. She flexed her fingers gingerly, wincing at the stiffness creeping into her shoulder.”

Severity Levels

Not all bruises are created equal. Use the severity of the bruise to influence how much it affects your character.

Mild Bruise (Grade 1)

Symptoms: Minor pain, small and localized discoloration.

Impact: Little to no effect on mobility.

Recovery Time: A few days.

Moderate Bruise (Grade 2)

Symptoms: Significant pain, noticeable swelling, and larger discoloration.

Impact: Reduced mobility or discomfort during movement.

Recovery Time: 1–2 weeks.

Severe Bruise (Grade 3)

Symptoms: Intense pain, extensive discoloration, significant swelling, and possible complications like compartment syndrome (dangerous pressure buildup in tissues).

Impact: Difficulty using the affected area, possible need for medical intervention.

Recovery Time: Several weeks to months.

The Appearance of Bruises Over Time

Bruises change color as the body breaks down and reabsorbs the blood trapped under the skin. Including these stages can help ground your narrative in reality.

Red/Pink (Immediately): Caused by fresh blood pooling under the skin.

Blue/Purple (1–2 Days): As oxygen is depleted from the blood, the bruise darkens.

Green (5–7 Days): The body begins breaking down hemoglobin, causing a greenish tint.

Yellow/Brown (7–10 Days): The final stage of healing as the body reabsorbs the blood.

Use the changing appearance of a bruise to indicate the passage of time in your story.

Example: “The bruise on his forearm had faded to a sickly yellow, but the memory of the brawl still lingered. Every flex of his wrist brought a dull ache, a reminder of how close he’d come to losing the fight.”

Long-Term Effects of Severe Bruises

While most bruises heal without issue, severe contusions can have lasting consequences.

Chronic Pain or Stiffness: Deep muscle bruises may lead to ongoing discomfort, especially in overused areas.

Permanent Discoloration: Particularly large or deep bruises may leave faint discoloration or scar-like marks.

Psychological Impact: Bruises from traumatic events (e.g., abuse or combat) might serve as emotional reminders of the incident.

Example: “The bruise on her thigh had long since faded, but every time she saw the faint outline of a scar, she remembered the ambush and the fear that came with it.”

Using Bruises to Drive Plot and Character Development

Bruises can serve more than just a visual reminder of an injury—they can shape your character’s arc or influence the plot.

Physical Limitations: A bruised limb might slow your character’s progress or prevent them from performing certain tasks, creating tension.

Emotional Symbolism: Bruises can reflect a character’s resilience or highlight vulnerability, adding depth to their emotional state.

Conflict: A visible bruise might draw unwanted attention, creating questions or suspicions among other characters.

Example: “The bruise on her jaw was impossible to hide. As the council stared at her in silence, she could feel their questions hanging heavy in the air. She had survived—but at what cost?”

Depicting Bruises Across Genres

The way bruises are portrayed in fiction varies widely based on the genre. Factors such as the setting, technology, medical knowledge, or fantastical elements influence how characters receive, describe, and treat these injuries. Below, I’ll explore how depictions of bruises differ in contemporary, historical, fantasy, and science fiction genres, focusing on how genre-specific elements like armor or advanced medicine shape the narrative.

Contemporary

In contemporary settings, bruises are grounded in realism. They’re often caused by everyday events like falls, accidents, or altercations and treated with modern first aid or medical care.

Causes

Sports injuries, domestic abuse, car accidents, fistfights, or workplace mishaps.

Treatment

The RICE Method: Rest (avoid activities that stress the bruised area), ice (apply ice packs for 15–20 minutes every few hours to reduce swelling), compression (use elastic bandages to minimize swelling and provide support) and elevation (eep the bruised area elevated to reduce blood pooling).

Pain Relief: Over-the-counter medications like ibuprofen or acetaminophen are used for pain and inflammation.

Physical Therapy (For Severe Bruises): Rehabilitation exercises may be prescribed to restore mobility and strength after deep muscle bruises.

Description

Writers can focus on the visual progression of a bruise, the pain associated with movement, or how it draws attention in social settings.

Narrative Impact

Visible Symbolism: A black eye might serve as a visible reminder of a fight, leading to questions or assumptions from others.

Emotional Weight: Bruises may highlight vulnerability in abuse survivors or evoke empathy for a struggling character.

Physical Challenges: Deep bruises (e.g., on ribs or legs) could slow down a protagonist, creating tension in action-oriented plots.

Example: “The bruise on her forearm was an ugly mottling of purple and yellow, a stark reminder of her collision with the pavement. She winced every time she moved, clutching the coffee cup with her good hand.”

Historical

In historical fiction, bruises often reflect the physicality of the time period—manual labor, harsh punishments, or violent encounters. The limited medical knowledge of the era also shapes how these injuries are perceived and treated.

Causes

Physical labor, harsh discipline (e.g., lashings), battles with blunt weapons, or accidents involving primitive tools.

Treatment in the Ancient World

Herbal Poultices: Crushed herbs like comfrey (known as “knitbone”) and arnica were applied to reduce swelling and pain.

Cold Compresses: River stones or cloths soaked in cold water were used to reduce inflammation.

Massage and Oils: Gently massaging the area with olive oil or mustard oil to stimulate circulation and relieve stiffness.

Rituals and Superstition: Healing rituals, charms, or prayers were often used alongside physical treatments, reflecting spiritual beliefs.

Challenges: Limited understanding of internal injuries meant deeper bruises could lead to complications like blood clots or infections without proper care.

Treatment in the Medieval World

Herbal Remedies: Poultices made from arnica, chamomile, or sage were applied to bruises to reduce pain and swelling.

Warm Compresses: Heated cloths or herbal infusions were used to improve circulation and soothe aching muscles.

Bloodletting (Rarely for Bruises): Though not a common treatment for bruises, bloodletting was occasionally used if the injury was believed to disrupt the balance of humors.

Bone Setting (For Severe Bruises): Bruises near joints or bones were sometimes treated by barbers or surgeons who specialized in bone injuries.

Challenges: Poor sanitation and reliance on superstition often led to infections or mismanagement of injuries, especially for severe contusions.

Narrative Impact

Symbol of Hardship: A laborer might bear constant bruises as a sign of their grueling work.

Indication of Class or Status: Bruises could signify mistreatment, poverty, or hard labor, creating social tension.

Tension from Ineffective Medicine: Without modern tools, even minor bruises could lead to complications, adding stakes to the story.

Example: “My brother took in the sight of my bruised face in the lantern light. “What happened?” he sighed. “Never mind, I do not wish to know. But I suggest you cease your brawling and keep this from Father.”

Fantasy

In fantasy, bruises are shaped by the fantastical elements of the world. They may result from magical battles, blunt weapons, or encounters with mythical creatures. Armor, healing spells, and the nature of magic itself can also influence how bruises are described and treated.

Causes

Blunt trauma from maces, clubs, or fists. Magical attacks that cause internal damage without breaking the skin. Non-human opponents like trolls or dragons inflicting bruises with their sheer strength.

Treatment

Magical Healing: Spells or potions may instantly heal bruises, though they might come with side effects (e.g., draining the caster’s energy, leaving scars, or triggering magical aftereffects).

Enchanted Poultices: Herbs could have mystical properties that speed up healing when combined with incantations.

Healing Rituals: Priests or shamans might perform rituals invoking deities or spirits to heal bruises, often adding a dramatic flair to the recovery process.

Alchemical Treatments: Alchemists might create salves or tonics from rare ingredients to accelerate recovery and reduce pain.

Challenges: Limited access to magical resources or a healer might create tension, forcing characters to rely on slower, mundane methods.

Narrative Impact

Armor’s Role: Armor might prevent fatal wounds but leave characters bruised from the force of impacts. A knight might survive a blow to the chest plate but be left with a deep bruise that limits their movement.

Magical Complexity: A bruise caused by a cursed weapon or a magic spell might resist normal healing, creating a plot-driving dilemma.

Example: “Though the ogre’s club hadn’t broken her bones, the impact against her breastplate left her ribs aching and her chest mottled with dark bruises. She sipped the bitter tea the healer had brewed, hoping it would ease the stiffness before morning.”

Science Fiction

In science fiction, bruises often result from futuristic technologies, alien environments, or enhanced combat scenarios. Advanced medicine and technology significantly influence how these injuries are portrayed and treated.

Causes

Kinetic impacts from blunt weapons, exosuit malfunctions, or alien encounters.

Environmental factors, such as low-gravity falls or pressure injuries.

Experimental technology (e.g., force fields failing) causing internal contusions.

Treatment

Regenerative Gels: Applied to bruised areas, these gels repair blood vessels, reduce swelling, and heal tissue within minutes.

Nanobot Therapy: Tiny robots are injected into the bloodstream, targeting damaged capillaries and muscle tissue to accelerate recovery.

Healing Pods: Characters can lie in full-body pods that repair injuries at a cellular level using lasers, cryotherapy, or other advanced methods.

Exoskeletons or Biotech Augments: For characters with biomechanical enhancements, the injury might be repaired by the augment itself or integrated medical systems.

Challenges: Over-reliance on technology might create dilemmas if equipment malfunctions or alien infections complicate healing.

Narrative Impact

Combat and Protection: Characters might wear advanced armor or exoskeletons that prevent penetration wounds but amplify bruises due to kinetic force.

Alien Physiology: Non-human characters might experience bruises differently, such as bruises that change color to signal healing or injuries that glow due to unique biochemistry.

Example: “The impact of the alien’s strike sent her sprawling, the kinetic energy bypassing her suit’s shielding. By the time she staggered to her feet, a deep purple bruise was already blooming across her ribs, the nanobots in her bloodstream working overtime to dull the pain.”

Plot and Character Ideas

Bruises and contusions may seem like minor injuries, but they can play a significant role in storytelling. In science fiction and fantasy, where non-human physiologies or advanced technologies come into play, bruises can take on unique forms and meanings. Below are plot and character ideas centered on bruises and contusions, with specific examples for speculative genres.

The Slow Reveal of a Secret Battle

Genre: Any (especially Fantasy or Science Fiction)

Plot Idea: A character hides bruises that hint at secret struggles, whether from battles, training, or abuse. Over time, the injuries raise questions that unravel a deeper plot.

Character Angle: The character’s reluctance to discuss their bruises reflects their internal conflict—pride, shame, or fear. Their physical pain mirrors emotional or psychological scars.

Fantasy Twist: The bruises glow faintly, hinting at magical corruption from an enchanted opponent. The character struggles to keep their condition hidden as it worsens.

Sci-Fi Twist: The bruises are caused by an alien parasite or malfunctioning implants, and the character races to find a cure before their condition becomes fatal.

Example: “The dark marks on his arms weren’t from sparring, though that’s what he told the others. Beneath his cloak, the bruises shimmered faintly, spreading further each day. Whatever magic had struck him, it wasn’t done yet.”

The Healer’s Challenge

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A healer is confronted with a patient whose bruises resist all traditional and magical treatments. The source of the injury reveals a deeper magical curse or secret enemy.

Character Angle: The healer must confront their self-doubt as they struggle to cure the patient while uncovering the mystery of the unhealing bruises.

Fantasy Twist: The bruises are caused by cursed armor or a weapon enchanted to harm over time. The healer must craft a counter-spell using forbidden techniques.

Example: “No matter how many salves she applied, the bruises darkened, as if feeding on the patient’s life. The only clue lay in the sword that caused them—a blade etched with runes she’d never seen before.”

The Alien Symptom

Genre: Science Fiction

Plot Idea: A non-human character’s bruises appear differently from those of their human companions, offering clues to their physiology and the limits of their durability. The unique injury becomes critical to solving a larger problem.

Character Angle: The character’s injury forces them to rely on others, creating tension or strengthening bonds. The injury also sparks revelations about their culture or biology.

Sci-Fi Twist: The alien’s bruises glow, expand, or emit sound as their body attempts to heal, causing confusion and potential danger to the rest of the team.

Example: “The bruises spread in geometric patterns across her iridescent skin. When they began to hum faintly, the crew’s medic stepped back nervously. ‘Is that normal for your species?’ he asked. Her silence was not reassuring.”

The Warrior’s Legacy

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A character’s bruises from a recent battle become symbols of their resilience and determination. However, as the injuries worsen, they begin to question whether their pride is worth the pain.

Character Angle: The warrior struggles with balancing their reputation for strength with the reality of their injuries. They must decide whether to rest and recover or push through the pain, risking further damage.

Fantasy Twist: The bruises form patterns that resemble runes or prophecies, hinting at the character’s larger destiny.

Example: “He refused to remove his armor, hiding the deep bruises along his ribs. Each step sent a jolt of pain through his chest, but he kept walking. His people needed a strong leader, not a wounded one.”

The Unusual Side Effect

Genre: Science Fiction

Plot Idea: A character suffers bruises from using experimental technology or alien artifacts, but the injuries come with bizarre side effects like enhanced abilities, hallucinations, or a telepathic connection to the artifact.

Character Angle: The character must weigh the benefits of their new abilities against the growing physical toll on their body.

Example: “The bruises spread like ink beneath his skin, pulsing faintly with each beat of his heart. He could feel something shifting in his mind—new thoughts, alien and unfamiliar, whispering secrets he couldn’t ignore.”

The Accidental Message

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A character’s bruises form unusual patterns that resemble ancient symbols or a map. The injuries suggest they are part of a larger prophecy or divine plan.

Character Angle: The character is torn between disbelief and destiny, unsure whether to follow the path suggested by their injuries.

Fantasy Twist: The bruises were caused by a magical beast or relic, and they shift or fade as the character approaches certain locations.

Example: “The bruises on her arms formed jagged lines, too precise to be random. As the moonlight struck her skin, they glowed faintly, and she realized they outlined the mountain range she’d seen in her dreams.”

The Gravity of War

Genre: Fantasy or Science Fiction

Plot Idea: After a brutal battle, a character is covered in bruises, symbolizing the physical toll of war. Their recovery process serves as a backdrop for exploring themes of resilience, camaraderie, and the consequences of violence.

Character Angle: The character’s bruises become a visible reminder of their vulnerability, leading them to reconsider their role in the conflict or how they perceive their comrades.

Fantasy Twist: A fellow soldier uses magic to share the burden of pain, creating a bond between the two.

Sci-Fi Twist: The character’s bruises reveal weaknesses in their exosuit or armor, prompting a mission to upgrade their gear.

Example: “Each bruise was a memory—a blow narrowly avoided, a fall that could have ended him. He traced a hand over his ribs, wincing at the deep purple marks. The war was over, but the echoes of it lingered.”

The Heirloom Weapon’s Curse

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A magical weapon leaves bruises on its wielder, feeding on their vitality each time it’s used. The character must decide whether the weapon’s power is worth the cost.

Character Angle: The character’s growing collection of bruises serves as a physical manifestation of their moral struggle—are they willing to sacrifice themselves for the cause?

Example: “The bruises wrapped around his arms like shackles, darkening with every swing of the sword. He could feel the weapon drawing from him, but without it, they had no hope of victory.”

The Cultural Difference

Genre: Science Fiction or Fantasy

Plot Idea: In a multi-species or multi-culture setting, the appearance or treatment of bruises becomes a point of misunderstanding or conflict between characters.

Character Angle: The character must navigate cultural differences, balancing their own beliefs with the expectations of others.

Example: “The alien stared at her mottled skin, their bioluminescent face shifting colors in confusion. ‘You call this healing?’ they asked. ‘In my world, such marks are signs of decay.’”

The Hidden Strength

Genre: Fantasy or Science Fiction

Plot Idea: A character’s bruises, far from being a sign of weakness, are revealed to grant them strength, endurance, or magical abilities. The darker the bruises, the stronger they become, but the cost to their body grows over time.

Character Angle: The character must decide whether to embrace the power and risk permanent damage or find an alternative way to achieve their goals.

Example: “The bruises on her knuckles deepened, turning almost black as her strength surged. Each blow carried more force, but with it came a warning: her body could only take so much.”

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

The Writer’s Guide to Puncture Wounds

Posted on April 11, 2025 Leave a Comment

Puncture wounds are dramatic, high-stakes injuries that can add tension and danger to your story. Whether it’s a dagger through a knight’s side, a nail through a construction worker’s foot, or an alien claw piercing a space traveler’s suit, puncture wounds can create immediate peril and lasting consequences. Writing these injuries realistically requires understanding their types, symptoms, severity, and recovery process.

Types of Puncture Wounds

Puncture wounds occur when a sharp object pierces the skin and underlying tissues. The nature of the wound depends on the object and the depth of penetration. Here are several common types of puncture wounds.

Superficial Wounds

Shallow injuries caused by small or blunt objects (e.g., splinters, shallow nail punctures). Low risk but may still lead to infection if untreated.

Deep Wounds

Penetrate through skin, muscle, and possibly into organs or bone (e.g., knife stabs, arrow wounds). High risk of infection, bleeding, and internal damage.

Clean Wounds

Caused by sharp, smooth objects (e.g., surgical tools, needles). Easier to clean and treat, with lower infection risk.

Dirty or Contaminated Wounds

Caused by objects carrying dirt, rust, or bacteria (e.g., rusty nails, animal bites). Higher risk of infection, including tetanus.

Impaled Objects

The object remains embedded in the wound (e.g., a shard of glass or spear). Removal risks worsening bleeding or damage.

Symptoms of Puncture Wounds

Realistic descriptions of symptoms help bring the injury to life. Consider how symptoms evolve over time, from the moment of injury to days later.

Immediate Symptoms

Sharp, localized pain at the site of the injury.

Bleeding (may be minimal for small wounds or severe for deep ones).

Swelling and redness around the wound.

Possible foreign object embedded in the wound.

Delayed Symptoms (Hours to Days Later)

Increasing pain or tenderness.

Swelling or warmth around the wound, indicating infection.

Red streaks radiating from the wound, a sign of spreading infection.

Fever, chills, or fatigue in severe cases.

Severity Levels

The severity of a puncture wound can range from minor to life-threatening, depending on the object, location, and depth.

Mild Puncture Wounds

Shallow and clean, affecting only the skin and surface tissues.

Low risk of infection if properly cleaned.

Recovery: A few days to a week.

Moderate Puncture Wounds

Deeper penetration, potentially damaging muscles or blood vessels.

Higher risk of infection or complications if not treated promptly.

Recovery: 1–4 weeks, depending on the location and care provided.

Severe Puncture Wounds

Penetrate vital organs, arteries, or bones.

Risk of internal bleeding, organ damage, or septic shock from infection.

Recovery: Weeks to months, potentially requiring surgery or long-term care.

Treating Puncture Wounds

Treatment depends on the resources and knowledge available in your story’s world.

Stop the Bleeding: Apply direct pressure with a clean cloth or bandage.

Clean the Wound: Rinse with clean water or antiseptic if available. Avoid removing impaled objects without medical assistance.

Dress the Wound: Cover with a sterile bandage to prevent contamination.

Recovery Process

The recovery timeline for a puncture wound depends on its severity and the quality of care received.

Initial Healing (1–3 Days)

Scab formation to protect the wound.

Swelling and redness begin to subside if there’s no infection.

Tissue Repair (1–2 Weeks)

New tissue grows to close the wound.

Stiffness or soreness may linger in the affected area.

Full Recovery (2–6 Weeks or Longer)

Deeper wounds take longer to heal and may leave scars.

Lingering pain, stiffness, or weakness is possible in severe cases.

Example: “Though the wound had closed, the scar tissue pulled tight whenever he moved his arm. He flexed his fingers slowly, wincing at the lingering stiffness.”

Long-Term Effects

Puncture wounds can leave lasting consequences, especially if complications arise.

Scarring: Deep wounds often leave visible scars, which can carry emotional weight.

Chronic Pain or Weakness: Nerve or muscle damage may cause persistent pain or reduced mobility.

Infections and Complications: Untreated infections can lead to abscesses, sepsis, or even amputations in severe cases.

Psychological Impact: The trauma of a near-fatal wound may cause anxiety, nightmares, or PTSD.

Example: “The sight of the dagger scar on her side always sent a shiver down her spine. It was a reminder of how close she’d come to death—and how much she still had to fight for.”

Depicting Puncture Wounds Across Genres

The way puncture wounds are portrayed varies greatly depending on the genre. The tools used to inflict the injury, the available medical treatments, and the cultural or technological context all shape how such wounds are described and treated. Below, I’ll explore how these depictions differ in contemporary, fantasy, science fiction, and historical genres, focusing on elements like armor, advanced medicine, and unique world-building considerations.

Contemporary Genre

In a modern setting, the portrayal puncture wounds are typically focuses on realism, with the injury’s severity often driving the plot or adding tension.

Causes: Knife attacks, construction accidents, gunshot wounds (bullet holes are a type of puncture), animal bites, etc.

Description: Focus on sharp, immediate pain, minimal external bleeding (depending on the depth), and visible entry points.

Treatment: First aid (cleaning, bandaging, applying pressure), followed by hospital care like antibiotics, stitches, or surgery.

Role of Armor: Modern armor such as Kevlar exists, although it is normally only used by military and police.

Impact on Characters: Characters will have access to modern medical care, but infections, complications or chronic pain can still create tension. Psychological impacts, such as trauma or fear, may play a significant role in the aftermath of the injury.

Example: “The knife slid between his ribs with horrifying ease. Pain bloomed in his side as blood seeped through his shirt, but adrenaline kept him moving. He’d have to make it to the hospital before shock set in.”

Fantasy Genre

Elements like enchanted weapons, armor, and magical healing methods add unique dimensions to how these injuries are portrayed.

Causes: Sword thrusts, arrow shots, enchanted spikes, monster claws, etc.

Description: Emphasis on the dramatic (e.g., the gleaming arrowhead protruding from the flesh) and the injury’s immediate impact on the character’s ability to fight or cast spells.

Treatment: Herbal poultices, salves, or magical healing. Wounds inflicted by cursed or poisoned weapons may require specific countermeasures or rare ingredients.

Role of Armor: Armor may deflect or reduce the severity of a puncture wound, but a well-placed strike can bypass protection (e.g., through a joint or visor). Descriptions might highlight the clash of steel on steel or the sound of a blade piercing chainmail.

Impact on Characters: Wounds often carry symbolic or narrative weight (e.g., a hero’s scar becomes a mark of honor). Wounds may also extend beyond the physical and involve magical scars or curses. Characters might undertake quests to find healers or rare remedies, turning the injury into a plot-driving element.

Example: “The arrow buried itself deep in her thigh, just above the leather greave. Pain flared as she snapped the shaft, the jagged edges grinding against bone. The healer’s face paled as she examined the cursed black fletching. ‘This will take more than herbs to cure.’”

Science Fiction Genre

In science fiction, the focus is often on the technological and futuristic aspects of treatment.

Cause: Energy-based weapons, high-tech projectiles, alien biology (e.g., acidic stingers), debris from space accidents, etc.

Description: Futuristic elements like glowing wounds from plasma burns or organic, self-repairing skin pierced by biomechanical implants. The lack of gravity in space might also influence the flow of blood.

Treatment: Regenerative gels, nanobot-assisted tissue repair, or med-bay pods that diagnose and heal punctures within minutes.

Impact of Advanced Medicine: Quick or near-instant recovery may reduce physical limitations but could come with ethical or emotional consequences (e.g., trauma from reliving the injury during neural regrowth). Scarless healing could contrast with the character’s psychological scars, providing opportunities for deeper storytelling.

Role of Armor: Power suits and energy shields may exist in your sci-fi world that provide some protection.

Example: “The alien claw had punched clean through his armor, leaving a jagged hole in his side. He gritted his teeth as the med-bot injected nanobots into the wound. The pain subsided as they worked, but the strange tingling left him wondering what else they were fixing beneath his skin.”

Historical Genre

Historical depictions of puncture wounds often stem from battles, duels, or accidents involving tools and weapons. Treatment reflects the limited medical knowledge of the time, creating a rich source of tension and conflict.

Cause: Arrow shots, sword thrusts, bayonets, agricultural tools (e.g., pitchforks), etc.

Description: Realistic accounts of pain, bleeding, and the risk of infection. Writers may highlight the limited nature of treatment, including unsanitary conditions and the use of rudimentary tools.

Treatment: Wounds were often cauterized with hot metal, treated with poultices, or stitched without anesthesia. Tetanus and sepsis were common and often fatal.

Role of Armor: Chainmail, plate armor, or leather could reduce the risk of deep punctures but wouldn’t prevent all injuries. Descriptions might focus on the sound of metal being pierced or the character’s surprise when armor fails.

Impact on Characters: Characters might deal with long-term complications, such as chronic pain, sepsis, limited mobility, or lasting infections. Social or political repercussions could arise if the injury marks them as weak or unfit for leadership.

Example: “The spear pierced his mail and bit deep into his shoulder. His vision swam as blood trickled down his arm, soaking into the padded gambeson beneath. The surgeon worked quickly, his tools clanging ominously. ‘We’ll need to cauterize,’ he said grimly, heating the iron in the brazier.”

Treating Puncture Wounds Across Time

The treatment of puncture wounds has evolved dramatically over time, from rudimentary practices in the ancient world to modern surgical techniques. In speculative genres like fantasy and science fiction, healing methods can be further enriched by world-building, introducing magical or futuristic solutions. Let’s explore how treatments differ across historical periods and how they might be imagined in fantasy and sci-fi contexts.

Ancient World Treatments

In ancient times, medical knowledge was limited, and treatments often relied on natural remedies, trial-and-error, and cultural or religious practices.

Typical Treatments

Cleaning the Wound: Water, wine, or vinegar was used to cleanse wounds, as these were believed to have antiseptic properties.

Herbal Poultices: Herbs like garlic, honey, and yarrow were applied to prevent infection and promote healing.

Stitching and Bandaging: Wounds were sewn using animal sinew or plant fibers and covered with linen or animal hides.

Cauterization: For deeper wounds, hot iron or boiling oil was used to seal the injury and stop bleeding, though this often caused severe tissue damage.

Challenges

Limited knowledge of germ theory meant infections were common, and many patients succumbed to sepsis or tetanus.

Example: An ancient healer might cleanse a warrior’s arrow wound with wine before applying a poultice of crushed yarrow and honey, chanting prayers to appease the gods of healing.

Medieval World Treatments

The medieval period saw incremental advances in wound care, influenced by religious practices and early surgical techniques. However, treatments were still crude by modern standards.

Typical Treatments

Antiseptic Poultices: Ingredients like comfrey, mugwort, or aloe vera were used to reduce inflammation and fight infection.

Bloodletting and Balancing Humors: Doctors believed in balancing the body’s humors and might perform bloodletting to “purge” toxins.

Cauterization and Stitching: Deep puncture wounds were either sewn shut or cauterized with heated metal.

Honey and Vinegar: Applied to wounds to create a protective barrier and reduce bacterial growth.

Amputation: For infected or gangrenous wounds, amputation was often the last resort.

Challenges

Unsanitary tools and poor understanding of infection made recovery difficult. Death from tetanus or blood poisoning was common.

Example: After being struck by a spear, a knight might be taken to a monastic healer who stitches the wound with rough twine, applies a paste of comfrey, and prays over the patient’s fevered body.

Contemporary Medicine

Modern medicine offers a variety of effective, evidence-based treatments that drastically improve outcomes for puncture wound patients.

Typical Treatments

Cleaning and Debriding the Wound: The wound is flushed with sterile saline or antiseptics to remove dirt, debris, and bacteria.

Antibiotics: Prescribed to prevent or treat infections, especially for deep or contaminated wounds.

Tetanus Shot: Administered if the patient’s vaccination is outdated or the wound is at high risk for tetanus.

Stitches or Surgical Repair: Deep wounds may require sutures or surgical intervention to close and repair damaged tissue.

Pain Management: Over-the-counter pain relievers or prescription medication for severe cases.

Challenges

Even with modern care, delayed treatment can lead to infections or complications like abscesses and sepsis.

Example: A character injured in an industrial accident might rush to an emergency room, where doctors clean the puncture wound with antiseptics, administer a tetanus shot, and prescribe antibiotics to ensure a smooth recovery.

Treatments in Fantasy Settings

In fantasy worlds, puncture wounds can be treated using herbal remedies, magical healing, or a combination of both. These treatments often align with the level of technology and the presence of mystical elements in the world.

Typical Treatments

Herbal Elixirs and Poultices: Herbs like goldenroot or silverleaf could be used for their magical antiseptic properties.

Magical Healing: Healing spells or enchanted artifacts might instantly close wounds, though these methods may have limits (e.g., cannot reverse internal damage).

Sacrificial Healing: A healer might transfer the wound’s pain or damage to themselves, creating moral and emotional dilemmas.

Rituals and Blessings: Religious figures could invoke the favor of healing deities to cure wounds, though success might depend on the character’s faith or the alignment of mystical forces.

Fantasy Challenges

Magical treatments could have side effects, such as lingering pain, scarring, or the transfer of curses. Additionally, some remedies may be rare or require dangerous quests to obtain.

Example: The elven healer murmured an incantation, and her hands glowed faintly as she passed them over the puncture wound. The bleeding stopped, but the warrior felt a strange chill settle in his bones, a reminder that magic always left its mark.

Treatments in Science Fiction Settings

In science fiction, medical advancements allow for innovative and highly effective treatments of puncture wounds, often blending biology with technology.

Typical Treatments

Regenerative Gel: A bio-engineered gel that seals wounds instantly and promotes rapid cell regeneration.

Nanobot Surgery: Microscopic robots repair internal damage, sterilize the wound, and prevent infection at a cellular level.

Tissue Cloning and Replacement: Damaged organs or muscles are replaced with 3D-printed or lab-grown tissue, ensuring a full recovery.

Cryo-Healing Pods: The patient is placed in a suspended animation pod that uses advanced techniques to heal wounds and restore health over time.

Energy Shields and Armor: Advanced protective gear may reduce the likelihood or severity of puncture wounds by deflecting projectiles or absorbing impact.

Sci-Fi Challenges

Over-reliance on technology might lead to malfunctions, delays, or ethical dilemmas (e.g., using alien-derived tech with unpredictable side effects).

Example: The med-bay hissed as the healing pod sealed shut, immersing her in a regenerative suspension fluid. Tiny lights flickered along the edges of her wound, where nanobots worked tirelessly to repair tissue and flush out alien toxins.

Plot and Character Ideas Revolving Around Puncture Wounds

Puncture wounds are versatile plot devices, adding immediate physical peril, emotional depth, or even long-term consequences. In science fiction and fantasy, where non-human physiologies or advanced technologies come into play, these injuries can take on unique forms and implications. Below are plot and character ideas centered around puncture wounds, with specific examples for speculative genres.

The Poisoned Wound

Genre: Fantasy / Science Fiction

Plot Idea: A character suffers a puncture wound from a poisoned weapon or creature. The poison spreads rapidly, forcing them to seek an antidote while battling the physical and mental effects of the toxin.

Character Angle: The character must face their fears of vulnerability or mortality, all while navigating dangerous terrain or negotiating with hostile factions to obtain the cure.

Fantasy Twist: The poison can only be neutralized by an ingredient found in a forbidden forest guarded by ancient creatures.

Sci-Fi Twist: The venom comes from an alien predator, and its antidote is synthesized from the creature’s DNA, requiring the team to capture a live specimen.

Example: “The barbed arrow lodged deep in his thigh, its edges slick with a dark green poison. Already, his vision blurred, and his heart raced uncontrollably. ‘The antidote,’ the healer said grimly, ‘lies beyond the Shadow Rift.’”

The Cursed Puncture

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A character is stabbed by a cursed weapon, and the wound refuses to heal. The curse manifests as physical pain or hallucinations, gradually consuming their mind unless the weapon’s curse is lifted.

Character Angle: The character wrestles with growing paranoia or despair as the curse eats away at their body and soul, testing their mental and emotional resilience.

Fantasy Twist: The curse spreads like a dark, magical infection, and the character must confront a forgotten deity to break it.

Example: “The blade had barely nicked her, but already the black veins of the curse crawled up her arm. The priest shook his head. ‘You have seven days before it reaches your heart.’”

The Armor Piercer

Genre: Fantasy / Science Fiction

Plot Idea: A specialized weapon or projectile penetrates what was thought to be impenetrable armor, leaving a critical injury that changes the course of battle. The event forces the character to question their reliance on their gear and adapt their strategies.

Character Angle: The injury humbles a previously overconfident warrior, pushing them to rely more on wits, teamwork, or unconventional tactics.

Fantasy Twist: A dragon-scale armor is pierced by a rare metal that negates magical protection, leading the character to seek an ancient blacksmith to repair it.

Sci-Fi Twist: The puncture compromises a high-tech power suit, and the character must repair it in the middle of a hostile environment while evading further attacks.

Example: “The plasma bolt burned through the titanium plating, searing flesh beneath. Gasping, she tore off the ruined chest plate. ‘If they’ve figured out how to pierce our armor, none of us are safe.’”

The Self-Inflicted Wound

Genre: Any

Plot Idea: A character intentionally causes a puncture wound to save themselves or others, such as by cutting their palm for a blood ritual or removing an embedded tracker.

Character Angle: The act of self-harm demonstrates the character’s determination and willingness to sacrifice for the greater good, creating an opportunity for introspection or bonding with others.

Fantasy Twist: The character’s blood activates a magical artifact needed to save their village, but the artifact demands more blood each time it’s used.

Sci-Fi Twist: Removing a high-tech tracking device causes a chain reaction in the character’s cybernetic implants, endangering their life.

Example: “With a grimace, he drove the knife into his palm, letting the blood drip onto the runestone. ‘You won’t take them,’ he growled. ‘I’ll pay the price.’”

The Unhealable Wound

Genre: Fantasy / Science Fiction

Plot Idea: A character’s puncture wound fails to heal due to their unique physiology or external factors, such as magic interference or a biochemical anomaly. The persistent injury limits their abilities and forces them to seek unconventional solutions.

Character Angle: The character grapples with feelings of inadequacy as the unhealing wound becomes a physical and psychological burden, driving them to explore their heritage or embrace their weaknesses.

Fantasy Twist: The wound disrupts the character’s ability to channel magic, requiring a quest to find a legendary healer.

Sci-Fi Twist: The wound exposes the character’s hybrid alien DNA, forcing them to confront their identity and seek an off-world specialist for treatment.

Example: “The puncture wound beneath his ribs bled endlessly, no matter how many bandages they applied. ‘It’s not a normal wound,’ the medic whispered. ‘It’s rejecting our treatments. You need to find the Exarch.’”

The Betrayer’s Strike

Genre: Fantasy / Science Fiction

Plot Idea: A trusted ally inflicts a puncture wound on the protagonist during a moment of betrayal, throwing their plans into chaos and forcing them to rethink their alliances.

Character Angle: The betrayal creates emotional conflict, as the character must decide whether to seek vengeance or uncover the betrayer’s motives.

Fantasy Twist: The weapon used in the betrayal is enchanted, and its injury reveals the true nature of the betrayer’s allegiance to a hidden enemy.

Sci-Fi Twist: The betrayal involves a high-tech weapon that embeds a tracking device in the protagonist’s wound, endangering the entire team.

Example: “The dagger slid between his ribs, and he staggered back, eyes wide with disbelief. ‘Why?’ he rasped, clutching his side as his friend turned and disappeared into the shadows.”

The Healer’s Guilt

Genre: Fantasy / Science Fiction

Plot Idea: A healer is unable to properly treat a puncture wound due to magical interference, alien physiology, or insufficient resources. The failure haunts them, driving their arc as they seek redemption.

Character Angle: The healer’s guilt pushes them to train harder, take greater risks, or confront their own limitations, ultimately transforming them into a more capable or empathetic person.

Fantasy Twist: The healer must travel to a distant land to learn forbidden healing techniques to save future patients.

Sci-Fi Twist: The healer experiments with risky alien technology to develop better treatments, risking their career or life.

Example: “She pressed her hands over the wound, willing her magic to flow, but the dark energy that surrounded the injury repelled her power. ‘I’m sorry,’ she whispered, tears mixing with the blood on her hands.”

The Blood Debt

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A puncture wound is inflicted as part of an ancient blood pact or ritual, binding the character to a powerful entity. The wound remains as a mark of their servitude or as a source of power.

Character Angle: The character must grapple with the ethical implications of their newfound abilities and decide whether to uphold or break the pact.

Example: “The dagger sliced into his palm, and the ancient runes flared to life. A voice echoed in his mind, promising power in exchange for loyalty. The wound would never heal—a permanent reminder of the debt he now owed.”

The Alien Anatomy Dilemma

Genre: Science Fiction

Plot Idea: A non-human character suffers a puncture wound that behaves differently from human injuries. Their unique biology complicates treatment and reveals critical information about their species or physiology.

Character Angle: The injury forces the character to confront their alien nature, creating tension with human companions or revealing hidden abilities.

Example: “The spike had pierced her carapace, leaking a glowing blue fluid. ‘That’s not blood,’ the medic muttered, scanning the wound. ‘Whatever you are, you’re not entirely human.’”

The Scar That Speaks

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A puncture wound leaves a scar that carries magical properties, such as showing visions, speaking in cryptic whispers, or warning of danger.

Character Angle: The scar becomes both a tool and a burden, as the character must decipher its messages while dealing with the physical and emotional toll of their injury.

Example: “The scar on her shoulder pulsed with a faint glow, and the whispers returned, urging her to take the hidden path through the mountains. ‘This wound will never let me rest,’ she muttered, pulling her cloak tight.”

Puncture wounds offer a rich opportunity to add tension, vulnerability, and stakes to your story. By depicting realistic symptoms, treatments, and recovery processes, you can create compelling injury arcs that resonate with readers and deepen your characters. Whether you’re writing a gritty survival tale, a sweeping fantasy epic, or a futuristic sci-fi adventure, these tips will help you write puncture wounds that feel authentic and impactful.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

The Writer’s Guide to Sprains and Strains

Posted on March 28, 2025 Leave a Comment

Sprains and strains are common injuries that can add depth and tension to your story, especially in action-oriented or survival-focused plots. These injuries can challenge your characters without incapacitating them completely, providing opportunities for resilience, improvisation, and personal growth. Writing them realistically requires an understanding of their causes, symptoms, severity, and recovery. This article covers everything you need to know about sprains and strains, helping you create believable injury arcs for your characters.

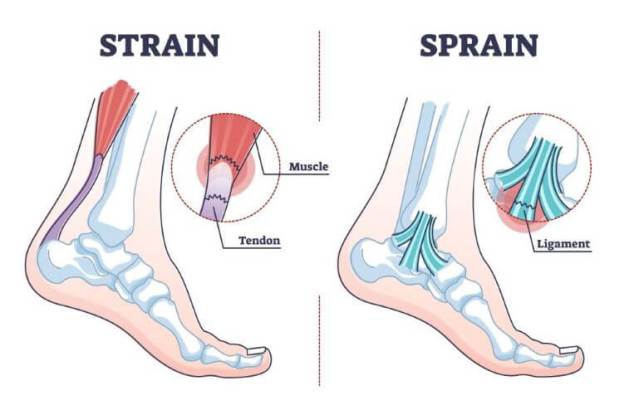

Sprains vs. Strains: What’s the Difference?

Although people often use the terms interchangeably, sprains and strains are different injuries. Understanding this distinction allows you to describe the injury more accurately and tailor it to your story’s needs.

Sprains involve overstretching or tearing of ligaments (tissues connecting bones at joints).

Commonly occurs in ankles, wrists, and knees.

Strains involve overstretching or tearing of muscles or tendons (tissues connecting muscles to bones). Commonly occurs in the back, hamstrings, and shoulders.

Example: A warrior running through uneven terrain may suffer an ankle sprain from a bad landing. A gymnast attempting an aerial routine may suffer a hamstring strain from overexertion.

Causes of Sprains and Strains

These injuries often result from accidents or overuse. Here are common scenarios:

Sprains

Twisting or rolling a joint (e.g., turning an ankle during a misstep).

Falling and landing awkwardly on a joint (e.g., catching oneself with an outstretched hand).

Sudden impacts or changes in direction (e.g., during sports or combat).

Strains

Overexerting a muscle during intense physical activity (e.g., lifting heavy objects).

Repetitive motion over time (e.g., swinging a weapon repeatedly).

Sudden pulling or overstretching of a muscle (e.g., dodging an attack too quickly).

Fantasy Twist

A character performing a powerful magical incantation might strain their arm muscles or neck tendons, leading to stiffness or lingering weakness.

Science Fiction Twist

A space traveler operating in reduced gravity might sprain an ankle during an unexpected fall or strain a shoulder muscle while lifting heavy equipment awkwardly.

Symptoms of Sprains and Strains

Realistic symptoms add credibility to your scenes. Both injuries share overlapping symptoms but differ slightly based on severity and location.

Symptoms of a Sprain

Pain: Felt immediately at the injured joint.

Swelling and Bruising: Caused by ligament damage.

Joint Instability: The joint may feel weak or unable to bear weight.

Limited Mobility: Difficulty moving the joint without pain.

Symptoms of a Strain

Muscle Pain or Spasms: Sharp or dull aches in the affected muscle.

Swelling and Stiffness: Localized around the muscle or tendon.

Weakness: Reduced strength in the affected area.

Limited Range of Motion: Difficulty stretching or flexing the muscle.

Severity Levels

The severity of a sprain or strain determines its impact on your character and the recovery timeline.

Mild (Grade 1)

Sprain: Ligaments overstretch, but do not tear.

Strain: A few muscle fibers have overstretched or torn.

Symptoms: Minimal swelling, mild pain, no significant loss of function.

Recovery Time: A few days to a week with rest.

Moderate (Grade 2)

Sprain: Partial tearing of the ligament.

Strain: More muscle fibers torn, noticeable weakness.

Symptoms: Swelling, bruising, pain during movement, reduced function.

Recovery Time: 2–4 weeks, possibly requiring physical therapy.

Severe (Grade 3)

Sprain: Complete ligament tear, possible joint dislocation.

Strain: Complete muscle or tendon tear, potential surgery needed.

Symptoms: Intense pain, severe swelling, inability to use the affected area.

Recovery Time: Several weeks to months, often requiring rehabilitation.

Long-Term Effects

Sprains and strains can leave lingering effects that add depth to your character’s journey.

Chronic Weakness: The injured area may remain prone to reinjury.

Reduced Mobility: Permanent stiffness or reduced range of motion.

Pain and Inflammation: Persistent aches during intense activity or bad weather.

Psychological Impact: Fear of reinjury might make the character hesitant or cautious.

Example: “Even months after the accident, her wrist still ached whenever she gripped her sword too tightly. She’d learned to adapt, but she doubted she’d ever fight the same way again.”

Treatments Across Time

The treatment of sprains and strains, from ancient poultices to futuristic nanotechnology, reflects your story’s setting and world-building. Whether your characters are relying on herbal remedies, enduring medieval bloodletting, or benefiting from high-tech regeneration, these injuries provide opportunities for realism, tension, and character growth. By incorporating accurate or speculative treatments, you can create an interesting and believable recovery arc that enhances your narrative. This section explores typical treatments from the ancient world, medieval world, and modern medicine, with speculation on what treatments might look like in the future.

Ancient World Treatments

In the ancient world, medical knowledge was based on observation, herbal remedies, and trial-and-error. While primitive by today’s standards, these methods often provided relief and basic healing.

Common Practices

Immobilization: People used strips of wood, bone, or plant stalks as makeshift splints to immobilize injured limbs. Wrapping with linen or animal hide helped stabilize the joint.

Herbal Poultices and Ointments: Comfrey, (known as “knitbone”), can reduce swelling and promote healing. Willow bark eases pain (contains salicylic acid, a precursor to aspirin). Turmeric and honey combined form an anti-inflammatory paste.

Massage and Warm Compresses: Gentle massage or heated stones applied to reduce stiffness and pain.

Rest and Observation: Rest was a crucial part of recovery, even if enforced by necessity rather than medical knowledge.

In Fiction

A shaman or healer could create a salve from rare plants to soothe a strained muscle, introducing an element of mysticism. A warrior might bind their sprained ankle with strips of animal hide to press onward, creating tension and stakes.

Example: “The healer ground comfrey leaves into a thick paste, smearing it over the knight’s swollen knee. ‘You’ll walk again,’ she promised, ‘but only if you stay off it for now.’”

Medieval Treatments

Medieval medicine combined ancient practices with emerging ideas from Islamic and European medical texts. Though still rooted in superstition, treatments became more structured.

Common Practices

Bandages and Supports: Leather straps, cloth bandages, or splints made from wood or bone were used to immobilize the injury.

Herbal Remedies: Arnica, applied as a poultice, reduces swelling and bruising. Practitioners used chamomile and lavender for their anti-inflammatory properties. They believed mugwort relieved pain when applied as a compress.

Bloodletting and Humoral Theory: Practitioners used bloodletting to “balance the humors” in cases of severe swelling, though this could be more harmful than helpful.

Warm Baths and Soaks: People sometimes treated injuries with warm, herb-infused baths believed to restore circulation and soothe muscles.

Prayers and Charms: Religious rituals, such as blessings or the use of holy relics, were common adjuncts to physical treatments.

In Fiction

A medieval monk might create a poultice from lavender and arnica to aid a sprain, emphasizing the blend of faith and medicine. A knight injured in battle might have their strained shoulder treated with heated herbal compresses, while their caregivers debate bloodletting.

Example: “The barber-surgeon tied splints around her swollen wrist with careful precision, muttering a prayer to Saint Roch. A poultice of arnica and chamomile would soothe the pain, though it could do little for her pride.”

Fantasy Twist