The Writer’s Guide to Venom

Posted on August 15, 2025 Leave a Comment

Venom is a biological weapon with bite – fast, deadly, and often misunderstood. Nature has used it for millions of years to paralyze, kill, or subdue prey, and it makes a powerful storytelling device in fiction. Whether your character is battling a serpent in the jungle, stung by a sci-fi insect, or cursed by a mythical creature, understanding how venom works in the real world can help you write scenes that are both gripping and grounded.

This article will walk you through the different venoms, their symptoms, the treatments, and how to use venom in your story to raise tension and make consequences matter.

What Is Venom?

Venom is a toxic substance actively delivered into the body through a bite, sting, or specialized organ (like fangs or a stinger). It differs from poison, which must be ingested, inhaled, or absorbed. In fiction, they’re often confused, but their effects and delivery systems are distinct.

If it bites you and you die, it’s venom.

If you bite it and die, it’s poison.

Types of Venom and Their Symptoms

Venoms come in several forms, each affecting the body differently. Many creatures deliver combinations of these toxins, which complicate diagnosis and treatment.

Neurotoxic Venom

What it does: Attacks the nervous system.

Symptoms: Muscle weakness or paralysis. Difficulty speaking or swallowing. Respiratory failure. Drooping eyelids (ptosis). Numbness or tingling.

Symptom Onset: Within minutes to 2 hours.

Animals: Cobras, mambas, kraits, blue-ringed octopus, cone snails, black widow spiders.

Great for fiction: High-stakes paralysis, inability to speak, ticking clock tension. Paralysis during a stealthy assassination, or characters gradually losing control of their body while trying to escape.

Hemotoxic Venom

What it does: Destroys blood cells, affects clotting, damages organs.

Symptoms: Internal bleeding. Swelling and bruising around the bite. Blood in vomit or stool. Organ failure (especially kidneys and liver). Shock.

Symptom Onset: 30 minutes to several hours

Animals: Vipers (e.g., rattlesnakes, puff adders), some lizards (Gila monster, Komodo dragon).

Great for fiction: Visceral, painful wounds; characters slowly weakening, disfiguring injuries. Graphic tissue damage, rapidly worsening injuries, or a sense of time running out because of organ failure.

Cytotoxic Venom

What it does: Destroys tissue and individual cells.

Symptoms: Severe pain at the bite site. Swelling and blisters. Necrosis (tissue death). Risk of amputation if untreated.

Symptom Onset: Hours to days.

Animals: Some vipers and spitting cobras, brown recluse spiders.

Great for fiction: Long-lasting scars, amputations, characters carrying trauma (and proof) of the encounter. Disfiguring wounds, delayed consequences of a bite, or lasting trauma after recovery.

Myotoxic Venom

What it does: Breaks down muscle tissue.

Symptoms: Intense muscle pain. Weakness or inability to move limbs. Dark urine (from muscle breakdown). Risk of kidney failure.

Symptom Onset: Hours, often with delayed symptoms. A warrior whose limbs weaken in battle, or a victim forced to choose between movement and further damage.

Animals: Sea snakes, certain rattlesnakes, some scorpions.

Great for fiction: Quiet internal damage, survivor guilt, delayed medical crises.

Cardiotoxic Venom

What it does: Attacks the heart

Symptoms: Irregular heartbeat. Chest pain. Cardiac arrest. Affects heart rhythm or damages cardiac muscle.

Symptom Onset: Within minutes to 2 hours.

Animals: Some cobras (particularly king cobras). Certain frogs and toads (more toxic than venomous via skin secretions)

Great for fiction: Collapse, near-death episodes, or deceptive slow-onset symptoms that mimic a heart attack.

Bonus: Unusual Venomous Animals

Platypus: Males have venomous spurs on their hind legs. Painful but non-lethal.

Cone snails: Beautiful but deadly, capable of delivering lethal neurotoxin through a harpoon-like tooth.

Box jellyfish: Their venom can stop the heart in minutes and cause irukandji syndrome, an intense, painful reaction.

Komodo dragons: Once thought to kill by bacteria, now known to inject anticoagulant venom to weaken prey.

Antivenoms, Treatments, and Survival Odds

Antivenom (Antivenin)

Made from antibodies produced by injecting venom into animals (usually horses or sheep).

Must be specific to the type of venom. Rattlesnake antivenom won’t work for a cobra bite.

Most effective when given early, within hours of the bite.

Additional Treatments

Supportive care (IV fluids, breathing support)

Wound cleaning and antibiotics (to prevent secondary infections)

Pain control

Surgical debridement (in cases of necrosis)

Survival Rates

In modern settings with access to antivenom: Very high, especially for North American and European bites.

In rural or undeveloped areas: Mortality remains high, especially for children and the elderly.

In historical or fantasy settings without modern medicine: Venomous bites can be fatal or permanently disabling.

Long-Term Effects of Envenomation

Even with treatment, survivors may experience:

Permanent nerve damage (neurotoxic)

Amputations (cytotoxic)

Chronic pain or arthritis

Kidney failure (myotoxic)

PTSD or trauma responses

Increased susceptibility to future envenomation because of immune sensitization

Characters may bear physical scars and emotional consequences, offering great depth to long-term arcs.

Depicting Venom in Fiction

Venom in fiction can be biological, mystical, or mechanical, depending on the world you build. Whether it’s a rattlesnake bite in the Wild West or a genetically modified arachnid on a terraformed planet, the way writers portray venom from its delivery to its consequences should reflect the genre you’re writing in.

In this article, we’ll explore how the depiction of venom changes by genre, focusing on contemporary and historical fiction, then diving into how fantasy and science fiction expand the possibilities through unique creatures and creative world-building.

Contemporary Fiction

Modern depictions of venom are rooted in biology and realism. Audiences expect accurate symptoms, treatment options, and a plausible chain of events.

Common Sources

Snakebites (rattlesnakes, copperheads, coral snakes)

Spider bites (black widow, brown recluse)

Scorpion stings

Exotic pets or illegal smuggling (e.g., Gila monsters, tarantulas)

Depiction Focus

Accurate symptom timelines: swelling, paralysis, neurotoxicity

Access to emergency medicine: antivenom, supportive care, logistics

Survival stories or medical thrillers: often involve race-against-time dynamics

Forensic clues: matching bite patterns, venom types, or sourcing rare antivenom as part of a mystery plot

Example: A rattlesnake bites a hiker miles from help. The story explores survival, improvisation, and the fragility of the human body against nature’s design.

Historical Fiction

In historical settings, people fear and misunderstand venom, attributing its symptoms to spirits, curses, or divine punishment rather than biology.

Common Sources

Native wildlife (e.g., snakes, insects)

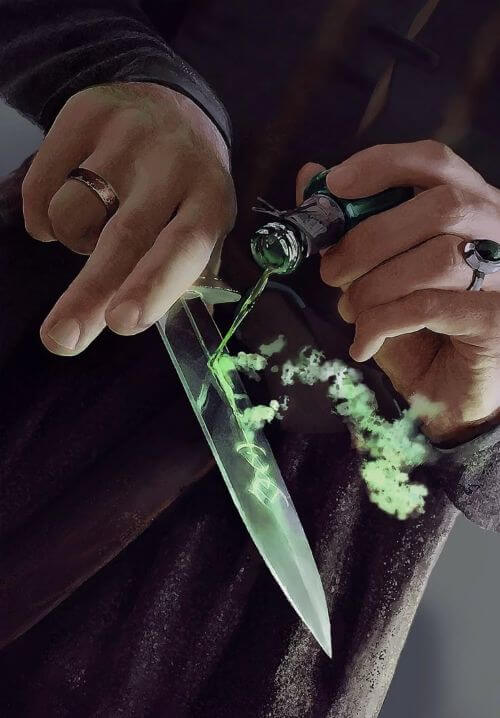

Assassin’s tools: poisoned daggers, venomous powders

Traditional medicine or folk practices involving animal toxins

Depiction Focus

Lack of diagnosis: venom symptoms mistaken for madness, witchcraft, or disease

Ineffective treatments: bloodletting, poultices, herbal purging

Social consequences: accusations of sorcery, revenge killings, political cover-ups

Symbolism: venom representing treachery, feminine danger, or divine wrath

Example: In a medieval court, a prince dies hours after a duel. They found a small, nearly invisible wound inflicted by a venom-dipped ring. No one understands how he died, and whispers of dark magic spread.

Fantasy

Fantasy allows for awe-inspiring interpretations of venom, where it doesn’t just cause physical harm, it may curse, transform, or alter fate.

Creatures with Venom

Basilisks, wyverns, shadow hounds

Giant spiders or serpents with mystical origins

Curse-bound familiars or enchanted beasts

Demons whose venom affects the soul, not just the body

Depiction Focus

Mythic symptoms: hallucinations, slow magical decay, memory loss

Unique cures: rare herbs, sacred rituals, blood oaths, divine intervention

World-specific logic: venom that only works on certain bloodlines or magical creatures

Plot consequences: a venomous wound might prevent the character from wielding magic or fulfilling a prophecy

Example: A dream serpent bites a rogue. Instead of dying, he loses the ability to dream, cut off from prophetic visions needed to save his realm. The cure lies with an ancient seer who charges a deadly price.

Science Fiction

In science fiction, venom can be biological, chemical, or technological. It might come from alien ecosystems, genetically modified organisms, or bio-weapons designed to bypass standard defenses.

Sources of Venom

Alien insects or reptiles

Cybernetic organisms with injector systems

Nanobot-delivered toxins

Bio-engineered hybrids (e.g., military experiments, terraforming accidents)

Depiction Focus

Complex reactions: venom that disrupts neural implants, hacks immune systems, or mutates cells

High-tech treatment: nanobots, AI diagnostic tools, gene therapy, cryostasis

Ethical questions: using venom in warfare, animal rights, or cross-species infection

Plot layers: a bite reveals the character’s biology is not what they thought

Example: An insect stings a colonist on a terraformed planet. It doesn’t kill her, but it rewrites her DNA, allowing her to breathe the alien atmosphere while severing her connection to Earth-based medicine.

Treating Venom Through the Ages

The treatment of venomous bites and stings has changed drastically over the centuries, evolving from herbal guesses and bloodletting to targeted antivenoms. In fiction, writers should match the treatment of venom to the period, culture, and genre, whether writing a medieval forest encounter, a modern survival thriller, or a futuristic bioengineered battlefield.

This section explores typical venom treatments from ancient times through modern medicine, with additional ideas for how fantasy and science fiction can expand or reinvent these methods in your story.

Ancient and Classical World

In early history, venom treatment was a mix of trial, error, ritual, and folklore. Snakebite and scorpion sting remedies were often based more on superstition than science.

Treatments

Suction and cutting the wound: A common but dangerous practice thought to “draw out” the venom

Burning or cauterizing the site

Herbal poultices and pastes made from garlic, onions, clay, or crushed insects

Incantations and amulets: Prayers, spells, or sacred texts placed on the wound

Venom stones (mythical “snake stones”) believed to absorb toxins

Consuming parts of the creature (e.g., powdered snake fang) to build immunity

Limitations

No understanding of how venom spreads through the bloodstream or lymphatic system

Most treatments were ineffective or harmful

Death was common, especially from neurotoxic or hemotoxic venom

In fiction: These treatments can introduce themes of desperation, folklore, or cultural belief systems, and create tension between healers and skeptics.

Medieval and Renaissance Treatments

By the Middle Ages, medical knowledge was still limited, though more structured thanks to translations of Greek and Roman texts. Some viewed venom as punishment for sin or a consequence of curses.

Typical Treatments

Bloodletting to “release bad humors”

Application of poultices made from herbs (yarrow, plantain, rue, wormwood)

Use of animals: Live chickens or pigeons were applied to bites to “draw out” the venom

Stone or mineral talismans believed to neutralize toxins when worn

Sweating therapies: Placing victims near fire to “sweat out” venom

Mystical remedies: People treated snakebites using relics, prayers, or pilgrimages

Limitations

No understanding of venom’s biological mechanism

Herbal treatments may have had mild antiseptic effects, but not venom-specific efficacy

Very few people survived serious bites from venomous animals without a strong immune response

In fiction: Use medieval treatments to emphasize the unknown. Let the healer succeed through instinct or experience rather than education, or explore the societal consequences of superstition and misdiagnosis.

Modern Medicine

Today, venom treatment is scientifically driven and highly effective when available. The challenge now is access, especially in remote or low-resource areas.

Standard Modern Treatments

Antivenom: Produced by injecting animals (usually horses or sheep) with small amounts of venom. Scientists harvest and purify the animal’s antibodies into injectable serum. Must be specific to the type of venom (e.g., rattlesnake vs. cobra). Works best when given within 4–6 hours.

Supportive Care: IV fluids, oxygen, and pain relief. Wound cleaning and antibiotics to prevent secondary infection. Surgical debridement if tissue necrosis occurs. Respiratory support for neurotoxic envenomation.

First Aid (Field Settings): Immobilize the limb. Keep the victim calm to slow venom spread. Do not cut or suck the wound. Get to medical care immediately.

Limitations

Antivenoms are expensive, have short shelf lives, and require cold storage

Not every country produces antivenoms for all species

Anaphylactic reactions to antivenom can complicate treatment

In fiction: Use modern treatments for survival thrillers, forensic investigations, or to add tension in remote settings where the cure is far away or expired.

Fantasy Treatments

In fantasy, venom can be mundane, magical, or cursed and the treatment should reflect the world’s logic and lore.

Common Fantasy Treatment Approaches

Alchemy and Potion Craft: Antidotes made from rare herbs, magical ingredients, or monster parts. Brews that only work if prepared under certain moons or rituals.

Healing Magic: Spells that purge toxins, but may require strength, sacrifice, or rare materials. Magical healing may work on wounds but not curses, or fail on enchanted venom.

Traditional or Forbidden Remedies: Old hedge-witch knowledge passed through generations. Cure tied to a trial or pilgrimage – a flower blooming on a cliffside, a beast’s venom used as its own cure.

Venom as a Curse or Trial

The venom doesn’t kill, but changes the victim – turns them to stone, steals memory, binds them to the creature

In fiction: Let the cure be part of the journey or character arc, something earned, not administered.

Science Fiction Treatments

In science fiction, venom can be biological, synthetic, or even programmable and treatments are often just as imaginative.

Advanced Sci-Fi Approaches

Nanobot Antidotes: Injected or activated to target and break down venom molecules. May fail against mutated or alien toxins.

Genetic Immunity: Engineered immunity for soldiers or explorers. A character discovers they’re immune or uniquely vulnerable based on ancestry or enhancements.

Neural Interface Diagnostics: Smart tech in suits or implants detects venom and deploys treatment instantly. May create tension if malfunctioning or hacked.

Alien Cures: Symbiotic organisms that absorb toxins. Venom must be treated with biologically incompatible medicine (e.g., from another species or environment).

In fiction: Use venom treatment to explore medical ethics, biotech dependence, or alien understanding of biology.

Plot and Character Ideas

Venom is more than just a toxin – it’s a symbol of stealth, power, danger, and transformation. Whether delivered by fangs, stingers, syringes, or enchanted blades, venom is visceral and intimate. It creates tension, limits time, and often leaves permanent consequences, making it a potent narrative tool across genres.

Below are plot and character ideas centered on venom, including twists for contemporary, historical, fantasy, and science fiction settings.

The Immunity Gambit

Genre: Fantasy / Historical

A noble house raises its heir on small doses of venom to build immunity in case of assassination. But when someone uses a rare venom against them, it doesn’t kill; instead, it causes hallucinations and compulsive truth-telling, threatening to expose the family’s darkest secret.

Character Angle: The heir must keep secrets while unable to lie. The venom’s effects grow stronger with each passing hour. The only cure lies in the hands of a rival house.

Twist: They developed the venom using the heir’s own blood; only the heir can survive a full dose.

The Venom Heist

Genre: Contemporary / Thriller

A pharmaceutical company is secretly harvesting rare venom from endangered species for an experimental drug. An eco-activist breaks in to expose them but gets stung and has hours to live unless she cooperates with the people she’s trying to stop.

Character Angle: A battle between survival, principles, and trust. The venom affects cognition. Was she hallucinating the evidence? Her only hope may be the scientist who created the drug.

Twist: The venom has a cognitive enhancement effect, and she realizes she’s not dying but changing.

The Crown of Fangs

Genre: Epic Fantasy

A ceremonial crown, once worn by a god-king, is encrusted with fanged serpents carved from obsidian. The new ruler dons the crown, and the serpents bite them, infecting them with divine venom. This venom slowly turns their blood to gold and their soul to madness.

Character Angle: The ruler’s decisions become more violent, visionary, or divine. A loyal guard or court healer must decide whether to cure, kill, or crown themselves. The venom allows glimpses into the minds of their enemies, but at what cost?

Twist: The venom was never meant to kill, it was meant to awaken a slumbering god.

The Entomologist’s Revenge

Genre: Mystery / Crime Drama

A reclusive entomologist creates a new breed of insect with engineered venom. When his daughter is murdered, the killer dies days later from a bite that leaves no trace. Now, a detective must solve a murder, searching for a murder weapon while wondering who the next victim will be.

Character Angle: The entomologist is both victim and suspect. The detective finds insect bites on themselves. Unless the antidote is administered in time, the venom mimics a natural death.

Twist: The killer recorded their confession but encoded in the insects’ behavior.

The Alien Bond

Genre: Science Fiction

An alien creature stings a space explorer on a newly colonized world. The venom begins to rewrite their DNA, adapting them to the planet. Now the explorer must decide: return to human form or fully bond with the new world?

Character Angle: The explorer gains heightened senses but loses language and identity. Their crew sees them as a threat or a miracle. They’re drawn to the alien ecosystem and something inside it is calling them back.

Twist: The planet uses venom to choose its guardians, and it has chosen them.

The Venom Oracle

Genre: Dark Fantasy

A secretive sect uses venomous creatures in their rituals. The sect claims that survivors of the creatures’ stings gain prophetic visions, but most victims die or go mad. A desperate character seeks the oracle’s guidance to save someone they love, knowing they may not survive the venom.

Character Angle: After the sting, they see possible futures but can’t control what they reveal. Each vision weakens their grip on the present. Others now seek them out for knowledge they never asked to bear.

Twist: They realize that they cannot change the future they saw unless they get stung again.

The Cure is Worse

Genre: Contemporary / Biopunk

A megacorporation unveils a miracle antivenom that works for every bite. But survivors show neurological side effects, including visions, rage, and in rare cases homicidal tendencies. A former EMT stumbles on the truth and must decide whether to expose the cure or protect the public trust.

Character Angle: The EMT was saved by the cure and is now seeing things that shouldn’t be real. The “venom” may not be from Earth. Trust in medicine, government, and self all unravel.

Twist: The antivenom’s purpose was never to cure, but to test compatibility with something to come.

The Dragon’s Pact

Genre: Mythic Fantasy

A dying land makes a pact with a venomous dragon whose bite grants supernatural endurance. To survive the journey through cursed territory, the dragon must bite a chosen champion; however, the venom alters them daily.

Character Angle: The champion struggles to maintain humanity and control. The venom grants visions of the dragon’s thoughts and memories. Companions grow fearful as their friend becomes something else.

Twist: The dragon didn’t choose them randomly. It’s preparing them as its successor.

The Synthetic Soldier

Genre: Sci-Fi / Military

Researchers injected genetically enhanced soldiers with controlled venom to boost their performance, but they abandoned the project after side effects spiraled out of control. Now one former soldier is being hunted by the corporation that created him and by the venom itself.

Character Angle: The venom amplifies instincts, aggression, and memory. Flashbacks blur past and present. He must track down the original scientist before the final mutation sets in.

Twist: The only antidote is inside a surviving test subject who wants to keep the venom’s power.

Venom isn’t just a monster’s bite. It’s a tool for tension, transformation, and consequences. When used right, it can slow a story down in the best way, letting readers sit with dread, pain, or desperation. Whether you’re writing fantasy, horror, or survival drama, venom can leave wounds that change characters forever.

Let your venom do more than harm. Let it shape the story.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

The Writer’s Guide to Poisoning

Posted on August 1, 2025 1 Comment

From Shakespearean tragedies to spy thrillers to medieval murder plots, poisoning has long been a favorite tool for fiction writers. It’s stealthy, dramatic, symbolic and, when done well, devastating. But writing poisoning realistically requires more than tossing a mysterious powder into a goblet. Readers today are savvy, and sloppy depictions can break immersion fast.

This article will help you write poisoning with accuracy, impact, and tension, while also clearing up one of the most common misconceptions in fiction: the difference between poison and venom.

Poison vs. Venom

Writers often confuse poison and venom, but understanding the distinction not only makes your writing more accurate, it opens up unique plot opportunities based on how each works.

Poison

A toxin that causes harm when ingested, inhaled, or absorbed

You eat it, drink it, breathe it, or touch it

Examples: arsenic, cyanide, hemlock, mercury, carbon monoxide

Venom

A toxin that causes harm when injected through a bite, sting, or specialized body part

It bites, stings, or stabs you

Examples: cobra venom, black widow venom, bee stings, cone snail harpoons

Simple Rule for Writers

If you bite it and die, it’s poison.

If it bites you and you die, it’s venom.

Understanding Real-World Poisons

People have used poison throughout history as a weapon of stealth, power, and fear. It’s a favorite of both assassins and storytellers because of its wide variety, subtlety, and dramatic potential. To write a realistic and compelling poisoning scene, it helps to understand the major categories of real poisons, how they’re administered, the symptoms they cause, and what determines a person’s survival or long-term prognosis.

Let’s break down the main poisons, their typical use or delivery, physiological impact, and a real historical case that shows just how powerful and insidious poison can be.

Neurotoxins

Effect: Attack the nervous system, disrupting signals between the brain, spinal cord, and muscles.

Common Examples: Botulinum toxin (Botox in small doses), sarin gas (nerve agent), tetrodotoxin (found in pufferfish), organophosphates (used in pesticides and chemical warfare)

Administration: Inhalation (nerve gases), ingestion (contaminated food, fish), injection (bio-weapons, animal venom)

Symptoms: Muscle weakness or paralysis, slurred speech, seizures, respiratory failure, loss of coordination or consciousness

Survival Odds: Low without immediate treatment, especially for nerve agents. Doctors may need to provide artificial ventilation until the body metabolizes the toxin.

Long-Term Effects: Neurological damage, chronic fatigue, reduced motor function

Ideal for stories involving: Political assassinations, bio-engineered weapons, elite toxin-based assassins.

Hemotoxins

Effect: Disrupt blood clotting, destroy red blood cells, or damage vascular tissue.

Common Examples: Ricin (from castor beans), arsenic, viper venom (in nature), warfarin (a blood thinner that can be toxic in large amounts)

Administration: Ingestion, injection (snakebite or weapon tip), inhalation (powdered toxins like ricin)

Symptoms: Internal bleeding, bruising, blood in stool or urine, organ failure due to lack of oxygen, circulatory collapse

Survival Odds: Moderate to low, depending on dosage and medical response time.

Long-Term Effects: Kidney or liver damage, anemia, impaired clotting or vascular issues

Great for stories involving: Sabotage, slow political assassination, long-term suffering masked as illness.

Cytotoxins

Effect: Kill or damage living cells directly.

Common Examples: Mustard gas, certain snake and spider venoms, chemotherapy agents in high doses

Administration: Skin contact, inhalation (airborne agents), injection (venoms)

Symptoms: Blistering skin, cell necrosis, organ failure, fever and fatigue

Survival Odds: Depends on exposure level, can range from full recovery to fatality.

Long-Term Effects: Scarring or disfigurement, increased cancer risk, autoimmune complications

Useful in fiction for: Visibly damaging poisons, dramatic transformations, magical or cursed toxins.

Gastrointestinal Poisons

Effect: Primarily attack the digestive system but may also cause systemic toxicity.

Common Examples: Strychnine, food-borne toxins (e.g., from spoiled mushrooms or seafood), ethylene glycol (antifreeze), cyanide (can also be classified as a metabolic toxin)

Administration: Ingested—commonly slipped into food or drink

Symptoms: Vomiting, diarrhea, severe abdominal pain, convulsions, difficulty breathing, collapse

Survival Odds: Higher if vomiting is induced early or if activated charcoal is administered. Some poisons (e.g., cyanide) can kill in minutes.

Long-Term Effects: Organ damage, nutrient malabsorption, ongoing GI disorders

Best for scenes involving: Tainted feasts, deceptive hosts, or suicide attempts with tragic consequences.

Metabolic Poisons

Effect: Disrupt cellular respiration and energy production.

Common Examples: Cyanide, carbon monoxide, fluoroacetate (a pesticide), methanol (in poorly made alcohol)

Administration: Inhalation (gas), ingestion (contaminated drink, pills), injection (less common)

Symptoms: Headache and confusion, seizures, cherry-red skin (cyanide), death because of cellular oxygen deprivation

Survival Odds: Very low without immediate treatment (e.g., antidotes, oxygen therapy)

Long-Term Effects: Cognitive impairment, memory loss, chronic fatigue

Great for science fiction, dystopias, or historical accidents involving gas exposure.

Historical Case Study: The Death of Georgi Markov (1978)

Who: Bulgarian dissident journalist living in London.

What Happened: While waiting at a bus stop, Markov felt a sharp sting in his leg. A man behind him dropped an umbrella and apologized before walking away. Markov later fell ill and died in the hospital.

The Cause: A tiny pellet filled with ricin had been injected into his leg via a modified umbrella gun, a KGB-linked assassination method.

Symptoms: Fever, vomiting, organ failure, death within days

Why It’s Notable: No antidote exists for ricin. It was deliberate, undetectable, and politically motivated.

This case remains one of the most infamous modern poisonings, illustrating how chillingly efficient the weaponisation of toxins can be.

In Fiction: Markov’s story shows how a minor encounter can carry fatal consequences and how poisons can instill fear and eliminate threats without a trace.

Consider creative setups: a poisoned letter sealed with a toxic powder, or a ceremonial dagger coated with plant extract that acts days later.

Detection and Treatment

In contemporary fiction, consider how forensic teams or toxicologists might uncover the truth. In historical settings, people might overlook poisoning, or blame it on curses, illness, or divine wrath.

Realistic Consequences

Antidotes may not exist (especially for rare or custom-made poisons)

Activated charcoal may help if caught early

Symptoms often linger, leaving survivors with lasting damage

Using Poison for Plot and Character Development

Poison is a weapon of choice of characters who are:

Cunning (a clever courtier who fakes her own death)

Desperate (a servant trying to end an abusive master)

Calculated (a ruler quietly eliminating threats)

Moral gray (a rebel leader debating whether to poison a tyrant)

You can also use poisoning to:

Frame someone

Create mystery (”Who drank from which goblet?”)

Provoke a race against time for the antidote

Symbolize betrayal (poison as the weapon of traitors and cowards)

Writing Poison Realistically

Do your research: Choose real poisons with plausible symptoms and timelines.

Use restraint: Poisons work best when they’re slow, suspenseful, and layered with character tension.

Don’t overcomplicate: A simple poison with realistic symptoms can be far more chilling than a magical instant-kill toxin.

Be consistent: If your world has magical or futuristic poisons, define the rules, how they work, who has access, and how they’re cured (or not).

Symptom Progression Matters

Most poisons don’t kill instantly. Even the deadliest, like cyanide or ricin, often take minutes to hours. Many (like arsenic or digitalis) act slowly over days, mimicking illness. That gives you time to:

Build tension (“Why is he sweating? Why can’t he speak?”)

Insert clues (“She didn’t drink the wine, did she?”)

Use delayed effects as a plot twist

Bad Example: The villain sips wine and drops dead in seconds.

Better Example: The villain begins to sweat, loses control of speech, and dies while gasping for air—just as the dinner host slowly backs away.

Poisoning in Fiction: How Genre Shapes Its Depiction

Poisoning is one of the most versatile tools a writer can use – stealthy, symbolic, and deeply personal. But how it’s used, perceived, and treated varies across genres. In contemporary and historical fiction, realism and accuracy take center stage. In fantasy and science fiction, the rules change, opening doors to creative concoctions, magical afflictions, and bio-engineered toxins that push the boundaries of imagination.

Let’s explore how the depiction of poisoning shifts by genre, with special attention to contemporary, historical, fantasy, and science fiction settings.

Contemporary Fiction: Forensics, Medicine, and Motive

In modern settings, poisoning must be scientifically plausible. Audiences expect realistic symptoms, timelines, and investigations. This often means:

Common Uses

Murder mystery or thriller: Poison chosen for being tasteless, slow-acting, or hard to trace.

Medical drama: Accidental overdoses, toxic exposure, or drug interactions.

Domestic or psychological thrillers: Slow poisoning by a caregiver, spouse, or parent.

Poison Types

Pharmaceuticals (e.g., opioids, insulin, antidepressants)

Household chemicals (e.g., antifreeze, cleaning agents)

Plant toxins (e.g., belladonna, hemlock)

Designer or synthetic poisons

Depiction Focus

Realistic symptoms and progression

Autopsy reports and toxicology

Access to medical intervention or delay thereof

Legal and ethical implications

Example: A cozy mystery where the killer slips digitalis into herbal tea. The sleuth uncovers it via symptoms (nausea, vision disturbances) and the victim’s medical history.

Historical Fiction: Secrecy, Symbolism, and Slow Death

In a pre-modern world, poisoning is often more feared than understood. With limited medical knowledge and rudimentary treatments, poisons can feel like superstition or divine punishment, which adds emotional and narrative tension.

Common Uses

Court intrigue and succession plots: Nobles and monarchs are poisoned at banquets or in their sleep.

Political assassinations: Cups, rings, or meals laced with toxins.

Folk remedies gone wrong: Accidental poisonings through herbal misuse.

Poison Types

Natural toxins (e.g., hemlock, aconite, arsenic)

Animal-based (e.g., snake venom applied to a blade)

Metallic poisons (e.g., mercury, lead, antimony)

Depiction Focus

Slow, agonizing deaths misdiagnosed as natural illness

Superstition and suspicion; characters may fear curses or witchcraft

Lack of antidotes, reliance on ritual, prayer, or herbal “cures”

Social consequences: Accusations of treason or witchcraft

Example: A medieval queen accused of witchcraft when a noble dies after a feast. The only evidence is his vomiting and convulsions but in a world with no autopsies, suspicion is all it takes.

Fantasy: Magical Toxins, Curses, and Symbolic Deaths

Fantasy allows you to break the rules of chemistry and biology. Poisons may not just kill, they may transform, curse, or corrupt.

Common Uses

Assassin guilds with signature toxins

Magical plagues tied to dark spells or forbidden herbs

Trial by poison, rituals where victims must survive ingestion to prove innocence

Poison Types

Cursed daggers that deliver soul-sickness

Enchanted venoms from mythical creatures (basilisks, wyverns, shadow hounds)

Alchemical elixirs that blur the line between poison and potion

Plants that only grow under moonlight, harvested by witches

Depiction Focus

Physical + mystical symptoms (visions, magical scarring, spiritual poisoning)

Cures require rare ingredients, sacred sites, or divine intervention

Dual-purpose poisons: may grant temporary powers before they kill

Cultural lore around the poison’s origin and moral weight

Example: A thief is poisoned by a ritual-bound relic. The poison won’t kill immediately, but each time he lies, the toxin spreads deeper into his body.

Science Fiction: Futuristic Toxins and Bioengineering

In science fiction, poisons become tools of precision warfare, genetic sabotage, or alien biology. Technology expands the concept beyond simple toxicity.

Common Uses

Targeted gene poisons: kill only individuals with certain DNA

Cyber-toxins: introduced via neural interfaces or implants

Atmospheric poisons: used for planetary control or terrorism

Alien biotoxins: immune to human treatment

Poison Types

Nanobot toxins: microscopic machines programmed to destroy cells or disrupt neural pathways

Engineered viruses: deliver lethal effects via infection rather than traditional poisoning

Synthetic molecules: bypass immune responses, only activated under certain conditions

Depiction Focus

Advanced delivery systems (aerosol, cybernetic implant, stealth drone)

AI medical scans and futuristic antidotes

Legal or moral questions: Was it a weapon or a medical experiment?

Delayed effects, sleeper agents, or memory-triggered activation

Example: A diplomatic envoy is poisoned via handshake. The nanopoison only activates after 48 hours, giving the assassin time to escape the system.

Poisoning Through the Ages: Treatments in History, Fantasy, and Science Fiction

Realistic poisoning isn’t just about the toxin, it’s about what happens after the poison is discovered. Who notices the symptoms? Is there a known cure? Does the character live with lasting damage, or are they doomed? Your genre and setting will significantly affect the answer.

In this section, we’ll explore typical treatments for poisoning from ancient times through modern medicine, then delve into how fantasy and science fiction can expand or complicate the possibilities.

Ancient and Classical Treatments

In the ancient world, people often misunderstood poisonings, feared them, and sometimes used them deliberately for executions or political purposes. Treatments were crude and based more on theory and superstition than science.

Typical Methods

Induced vomiting (using salt water, mustard, or herbs like ipecac)

Charcoal or clay ingestion (to “absorb” the toxin)

Bloodletting (to release the “bad humors”)

Herbal remedies believed to counteract poisons (e.g., rue, garlic, yarrow)

Theriacs: complex antidote mixtures, sometimes containing dozens of ingredients

Religious rituals: prayer, offerings, or exorcisms to “cast out” the poison

Limitations

No knowledge of dosage, absorption, or systemic effects

Treatments often did more harm than good

Death was common, even if the poison wasn’t particularly lethal

Great for fiction, where a character’s survival is a matter of superstition, desperation, or divine intervention.

Medieval and Renaissance Treatments

In the Middle Ages, treatments were still mostly guesswork but slightly more organized. Poisoning was a feared tool of assassins and nobles alike, and healers turned to herbology, alchemy, and early medical texts.

Typical Methods

Purgatives and emetics (to induce vomiting and diarrhea)

Poultices applied to the stomach

Amulets or talismans to ward off “bad air” or toxins

Antidotes made from animal parts, minerals, and plants

Testing for poison by feeding the food to animals or using silver to detect arsenic (a myth, but common)

Limitations

Most antidotes were broad-spectrum theriacs with little actual effect

Knowledge was often closely guarded or lost

Antidotes were prestigious, something only the wealthy could access

In your story, the rarity of a known cure could spark a quest, a bribe, or a betrayal.

Modern Medicine

Today, we understand poisons and how they work. Treatments have become targeted, rapid, and life-saving (when help is available in time).

Typical Treatments

Activated charcoal: Absorbs poison in the GI tract if administered early

Gastric lavage (stomach pumping): Less common now, used only in severe cases

Specific antidotes (e.g., naloxone for opioids, atropine for nerve agents, antivenoms)

Supportive care: IV fluids, oxygen, breathing assistance, medications to stabilize heart rate or blood pressure

Chelation therapy: For heavy metal poisoning (e.g., lead, mercury)

Dialysis: For cases of kidney failure or to filter toxins in the blood

Outcomes

High survival rate with timely intervention

Long-term effects vary depending on the poison and duration before treatment

For a mystery or thriller, modern medicine allows for dramatic near-misses, forensic tracing, and tense ICU scenes.

Fantasy Treatments

In fantasy, treatments for poison can be as imaginative and symbolic as the toxin itself. The cure may be magical, mythic, or tied to a prophecy or ritual.

Treatment Concepts

Healing magic: Spells that purge or neutralize toxins but may fail on cursed or magical poisons

Alchemical antidotes: Brewed with rare or magical ingredients (e.g., phoenix feather, bloodroot, shadowbloom)

Sacred rituals: Only a priestess, shaman, or oracle can cleanse the body or soul

Herbalism + lore: A village herbalist or hermit may hold knowledge passed through oral tradition

Poison immunity: Characters may build resistance through exposure (a trope seen in assassins or royals)

Fantasy poisons often resist normal healing, requiring the character to go on a journey or make a sacrifice to be cured, perfect for quest arcs.

Science Fiction Treatments

In sci-fi, treatments may be technologically advanced, highly precise, and potentially morally questionable.

Possible Approaches

Nanobots: Injected to locate and neutralize the toxin at the cellular level

Genetic editing: Rewrites affected DNA to repair damage or build resistance

Smart meds: Pills or patches that detect specific poisons and release tailored countermeasures

Bio-scans: AI-assisted diagnosis and chemical balancing in real time

Stasis chambers: Freeze the body until treatment is found

Alien cures: Extraterrestrial plants, symbiotes, or organisms that absorb or metabolize toxins

For speculative fiction, you can use poisoning to explore themes of biological warfare, genetic manipulation, or technological dependence.

Plot and Character Ideas

Poison is one of fiction’s most versatile tools. It can strike silently, act slowly, frame the innocent, or force the guilty to confess. Whether used in murder, mystery, betrayal, or healing, poison always carries weight, both literal and symbolic. It’s not just about death, it’s about intent, secrecy, and consequence.

Below is a range of plot and character ideas centered on poisoning, across genres like historical fiction, fantasy, science fiction, thrillers, and drama.

The Silent Assassin

Genre: Historical, Spy Thriller, Fantasy

A renowned poisoner-for-hire has never been seen, only their victims, who die with no trace of toxins. A desperate noble hires them, but the assassin’s moral code forbids targeting children and the client has lied about the intended victim.

Character Angle: The assassin has built immunity to dozens of poisons, but not to guilt. The target might be their own estranged relative. They’re being hunted by a rival who uses antidotes as blackmail.

Twist: The poisoner is already dying from a rare, slow poison they failed to detect in time.

The Experimental Cure

Genre: Science Fiction, Medical Thriller

A brilliant but disgraced scientist develops a synthetic poison that only kills cancer cells. When a corrupt biotech company steals her formula to create a targeted assassination tool, she must race to stop them before the first death.

Character Angle: Once labeled a “madwoman,” she’s now the only one who can stop a wave of invisible murders. She’s forced to team up with the test subject she accidentally poisoned.

Twist: The poison mutates and becomes airborne.

The Dinner Party Game

Genre: Contemporary, Mystery, Dark Comedy

A murder-mystery dinner party turns deadly when someone actually poisons a guest. With no way to leave, the guests must figure out who brought real poison to a pretend murder game.

Character Angle: The host is a failed mystery novelist trying to stage a comeback. One guest has immunity to the toxin and is using the chaos to exact revenge.

Twist: The wrong person dies and the actual target knows it.

The Taster’s Dilemma

Genre: Fantasy, Court Intrigue

A newly appointed royal taster discovers a slow poison in the queen’s food, but the queen already knows and has been building immunity. She plans to expose her enemies by surviving their plots. But the taster has their own agenda.

Character Angle: Torn between loyalty, survival, and ambition. Must taste-test all meals but isn’t immune like the queen.

Twist: The taster is the last living heir to a rival throne.

Genetic Poison

Genre: Science Fiction, Dystopia

A totalitarian regime uses a “clean poison” that only affects people with certain DNA markers. The girl’s survival of the targeted purge reveals that someone altered her genetics as a child, and she may not be who she thought she was.

Character Angle: Raised in ignorance of her origins, she becomes the key to overthrowing the regime. The resistance wants to use her blood as a universal antidote, but it will kill her.

Twist: Her own mother designed the poison to protect her from worse.

The Healer Who Kills

Genre: Historical, Folk Horror, Dark Fantasy

A village herbalist is accused of witchcraft after multiple nobles die of illness. She insists she gave them medicine, not poison, but someone else tampered with the herbs, and her reputation hides a deeper secret.

Character Angle: She was once a royal court alchemist, exiled for refusing to create a deadly toxin. Her knowledge of plants could save or destroy the kingdom.

Twist: She has a forbidden garden of “deadly cures” – plants that heal but at a steep cost.

The Poison Pact

Genre: Contemporary, Psychological Drama

Two terminally ill friends make a suicide pact using poison. One survives. As guilt sets in, they discover the poison wasn’t real, and now someone is manipulating them through staged “symptoms” and fear.

Character Angle: One of them questions their memory and sanity. The survivor must uncover who replaced the poison and why.

Twist: It was never about death, it was a test of loyalty and identity.

The Cursed Ink

Genre: Fantasy

A rare ink made from the venom of a dream serpent allows users to write living stories, but the ink is also toxic to anyone who tries to alter what’s been written. Someone blackmailed a scribe into forging a deadly prophecy.

Character Angle: Their hands tremble from constant exposure. They alone know how to create an antidote but revealing it would destroy centuries of lore.

Twist: The scribe’s own name has appeared in the poisoned script.

Accidental Killer

Genre: Contemporary, Legal Thriller

A food safety chemist discovers that a new preservative has become toxic under certain conditions. But when she tries to blow the whistle, her lab partner dies, and she’s framed for the murder.

Character Angle: She must prove her innocence while avoiding both the police and the real culprit. She has 72 hours before the product hits supermarket shelves.

Twist: Someone intentionally sabotaged the preservative to trigger a product recall war.

Poisoned Memories

Genre: Gothic Horror, Supernatural

A woman returns to her ancestral manor after her brother’s mysterious death. She begins to suffer hallucinations, memory loss, and physical symptoms, all pointing to poisoning. But the house has secrets and the toxin may haunt her mind as much as her body.

Character Angle: She uncovers a hidden lab used by their alchemist ancestor. The poison might not be physical, it might be etched into the house itself.

Twist: Her own bloodline was cursed with inherited sensitivity to the manor’s ancient fumes.

Poisoning is never just a way to kill, it’s a way to change the story. It can launch a mystery, deepen a betrayal, reveal secrets, or redefine identity. Whether your poison is brewed in a lab, stirred into a cup, written in a book, or whispered into a vial of magic, let it leave a mark that goes far beyond death.

In the best stories, poison lingers – on the lips, in the blood, and in the soul.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

The Writer’s Guide to Bites and Claws

Posted on July 18, 2025 1 Comment

Whether it’s a feral animal, a brutal hand-to-hand fight, or a supernatural creature sinking its teeth in, bites and claw wounds are savage, intimate, and dangerous. More than just blood and pain, these injuries carry high infection risks, complicated healing, and long-lasting trauma. In fiction, they’re often used to escalate tension, signal a character’s descent into danger, or mark the beginning of a supernatural transformation.

In this article, I’ll explore how writers can realistically portray bite and claw wounds, covering injury types based on the attacker, the location and depth, infection risks, and the survival odds and long-term consequences for your characters.

What Makes Bite and Claw Wounds Unique

Unlike clean cuts or bullet wounds, bites and claws are jagged, tearing injuries. They often:

Rip flesh rather than slice it.

Leave irregular, hard-to-stitch wounds.

Introduce bacteria, venom, or disease.

Cause deep puncture wounds that trap pathogens inside.

These aren’t surgical injuries, they’re primal.

Types of Bite and Claw Wounds by Attacker

Human Bites

Type: Blunt-force bite; tearing and crushing.

Severity: Often deep punctures with bruising.

Risk: Extremely high infection risk because of human mouth bacteria (Eikenella, Streptococcus, Staph).

Use in fiction: Prison fights, domestic violence, combat desperation.

Realism Note: Human bites to the hand or face are especially dangerous due to infection and nerve damage.

Dogs

Injury: Crushing wounds, torn muscles, punctures.

Common locations: Arms, legs, neck (especially with children).

Complications: Rabies risk, nerve damage, infection.

Cats

Injury: Sharp puncture wounds, usually deeper than they appear.

Risk: Extremely high for infection, especially Pasteurella multocida.

Locations: Hands and arms in defensive situations.

Rodents and Small Mammals

Injury: Small punctures, but higher risk of disease.

Risk: Hantavirus, rat-bite fever.

Snakes

Injury: Sharp puncture wounds with or without venom.

Risk: Extremely high, especially if venom was injected.

Large Predators (Bears, Wolves, Big Cats)

Bite: Bone-crushing force, often targeting the throat, abdomen, or limbs.

Claws: Long lacerations, deep gashes, often breaking through muscle.

Survival: Rare without immediate aid; limb loss and disfigurement are likely.

Example: A wolf’s bite can exert over 400 psi of pressure, enough to crush bones or sever arteries.

Supernatural or Fictional Creatures

Vampires, werewolves, or alien beasts may inflict both physical and magical or infectious damage. The bite may transform the character, trigger visions, or resist healing.

Tip: Ground these wounds in real-world trauma, then layer in the fantasy or sci-fi twist to keep it visceral and believable.

Location, Depth, and Weapon

Location Matters

Neck/Throat: Rapid blood loss, airway damage, extremely high fatality.

Hands/Fingers : High infection risk, nerve and tendon damage, loss of function.

Face: Disfigurement, psychological trauma, sensory loss (vision, hearing).

Legs/Arms: Arterial damage (femoral, brachial), limited movement, potential amputation.

Abdomen/Chest: Organ damage, internal bleeding, high infection risk, difficult recovery.

Depth and Nature of the Wound

Puncture wounds (fangs, claws) may look small but hide deep tissue damage.

Lacerations (swipes from claws) cause open wounds, muscle exposure, and severe bleeding.

Avulsions (skin torn away) are highly traumatic, requiring reconstructive surgery.

Type of Teeth or Claw

Flattened human teeth crush and tear.

Sharp feline claws slice clean but deep.

Canine teeth puncture and grip.

Raking claws from bears or reptiles can break bones and flay flesh.

Infection and Disease Risks

Bite and claw wounds are notorious for infection, especially when untreated or inflicted in dirty environments.

Common Complications

Cellulitis: Painful, spreading skin infection.

Abscesses: Pockets of pus needing drainage.

Sepsis: Life-threatening systemic infection.

Rabies: Fatal without post-exposure treatment.

Tetanus: Especially dangerous in deep, puncture-style wounds.

In low-tech or historical settings, infection is often the actual killer, not the wound itself.

Survival Odds and Long-Term Effects

Survival odds depend on:

Speed of treatment (especially with arterial or organ damage).

Cleanliness of wound care.

Access to antibiotics or magical/technological healing.

Strength and location of the bite/claw.

Long-Term Effects

Nerve or tendon damage leading to limited mobility or paralysis.

Disfigurement or scarring, especially from facial or neck wounds.

Psychological trauma, including PTSD, nightmares, or phobias.

Amputations in severe limb injuries.

Chronic pain and vulnerability to re-injury.

In fantasy and science fiction, surviving a bite might also mean being hunted, infected, or transformed.

Writing Tips for Realistic Bite and Claw Scenes

Show the aftermath, not just the wound. Pain, fear, fever, and emotional toll matter.

Don’t forget the mess: bites and claws are bloody, chaotic, and hard to treat.

Use medical logic even in magical or futuristic settings. Infection, tissue damage, and blood loss still apply.

Involve the senses: the warmth of blood, the rasp of breath, the jagged edge of a broken claw still in the skin.

Let scars have meaning, both physical and emotional.

Depicting Bites and Claw Wounds Across Genres

Bites and claw wounds are some of the most visceral injuries you can write, but how they’re depicted varies widely by genre. A modern dog attack, a medieval bear mauling, a vampire’s bite, or a cybernetic panther slash all demand different levels of realism, emotional tone, and narrative consequence.

This article explores how the portrayal of these wounds changes based on genre and how the creature inflicting the wound dramatically shapes the scene.

Contemporary

In contemporary fiction, accuracy is key. Readers expect depictions grounded in real-world biology, first aid, and emotional realism.

Common Causes

Dog attacks (domestic or wild).

Cat or rodent bites, especially in domestic abuse or self-defense situations.

Human bites in bar fights, riots, or desperate situations.

Wild animal encounters during camping, hunting, or disaster survival.

Depiction Focus

Wound detail: location, depth, shape (e.g., crescent-shaped human bite).

Medical response: bleeding control, tetanus shots, rabies treatments, antibiotics.

Psychological impact: fear, trauma, anxiety, PTSD.

Legal/Social implications: dog euthanasia, quarantine, lawsuits, assault charges.

Example: A loose pit bull attacked a jogger. The story may follow the victim’s hospitalization, the investigation into the dog’s owner, and emotional consequences like fear of going outside again.

In historical fiction, the same bite that’s survivable today might be fatal because of lack of sanitation, medicine, and understanding of disease.

Common Causes

Hunting accidents with wolves, bears, boars.

Battle injuries from war dogs or cavalry horses.

Punishment bites (e.g., gladiator pits, bear baiting).

Plague rats and wild animals in urban slums or during sieges.

Depiction Focus

Primitive wound care: cauterization, herbal poultices, or “bleeding the bad humors.”

Superstition: belief that an animal bite is a curse or divine punishment.

Slow deaths from sepsis, fever, or tetanus.

Scarring or amputation: long-term disfigurement as a social and physical consequence.

Example: A bear clawed a hunter. The village healer packs the wound with herbs, but fever sets in. The real tension lies in whether the character will live and what he’ll lose if he does.

Fantasy

In fantasy, bite and claw wounds often signal a deeper transformation or curse. The creature doing the damage may be mythical, cursed, divine, or undead.

Common Causes

Dragons, gryphons, wyverns: large-scale, devastating wounds.

Werewolves, vampires: transformative or infectious bites.

Demons or cursed beasts: magical wounds that resist healing.

Fey or spirit animals: claw wounds that mark the soul or alter fate.

Depiction Focus

Supernatural infection: wounds that burn with dark magic, mutate the victim, or pass along a curse.

Resistance to healing: traditional medicine or even magic fails unless special conditions are met.

Symbolism: the wound marks the character as chosen, doomed, or hunted.

Creature anatomy: enchanted talons, venomous saliva, or jaws that tear through steel.

Example: A rogue is clawed by a shadowbeast. The wound doesn’t bleed, but it spreads like smoke under the skin. No healer can stop it until he finds the ancient stag whose breath can cleanse all corruption.

Science Fiction

In science fiction, bite and claw wounds often come from alien organisms, genetically modified animals, or cybernetic creatures. These wounds may be biologically hazardous, weaponized, or biomechanically enhanced.

Common Causes

Xenomorphs or alien fauna with acidic saliva or infectious venom.

Cybernetic beasts with retractable claws, saw-toothed mouths, or energy-infused jaws.

Genetically engineered attack animals for security or warfare.

Bio-mech hybrids bred for stealth and assassination.

Depiction Focus

Futuristic medical intervention: nanobots, med-gel, auto-sutures.

Complex infections: alien pathogens, cyber viruses, mutagens.

Data disruption: in cybernetic characters, a claw slash may damage internal tech or wipe memory.

AI analysis of wounds: smart armor detecting and triaging injuries.

Example: An alien predator slashed a scout. The wound won’t clot because the creature’s enzymes keep it open. If left untreated, the enzymes will digest the surrounding tissue, turning the host into a breeding ground for larval implants.

Treating Bites and Claw Wounds Through History and Genre

Bite and claw wounds are more than traumatic injuries. They’re breeding grounds for infection, often jagged, dirty, and resistant to clean healing. Treatment has evolved dramatically over the centuries, shaped by the available tools, medical understanding, and cultural beliefs of the time. In fantasy and science fiction, the rules shift again, with access to magic or technology altering the outcome of what might otherwise be a deadly encounter. In every genre, from the battlefield tents of medieval wars to sleek medical pods aboard a starship, treatment is not just a step in the healing process. It’s a reflection of the world, its values, and its limitations.

This guide walks you through typical treatments for bite and claw wounds from ancient history through modern trauma care, and then explores what healing might look like in fantasy and science fiction worlds.

Ancient World Treatments

In ancient times, healing was a blend of observation, ritual, and limited herbal knowledge.

Typical Treatments

Cleaning the wound with wine, vinegar, or honey, substances known even then to slow infection.

Herbal poultices: crushed garlic, myrrh, or yarrow applied to promote healing or prevent rot.

Cauterization: burning the wound shut to stop bleeding and “purify” it.

Animal-based medicine: using fat, milk, or animal dung as poultices (sometimes worsening infection).

Ritual purification: chants, offerings, or talismans to ward off “spiritual poison” from animal bites.

Challenges

No antiseptics or antibiotics besides alcohol.

High rate of sepsis, tetanus, and gangrene.

Bites, especially from rabid animals, were often a death sentence.

Example: A Roman soldier bitten by a jackal has his wound washed in wine, bandaged in linen, and blessed by a priest, but fever sets in days later, and the question becomes whether to treat or amputate.

Medieval Treatments

While slightly more advanced than ancient methods, medieval medicine still relied heavily on theory over evidence, especially humoral balance and spiritual causes.

Typical Treatments

Wound irrigation with herbal infusions: sage, lavender, rosemary.

Bleeding and leeching: used to “draw out the bad humors” introduced by the bite.

Honey and silver: both natural antimicrobials, sometimes applied topically.

Tying with moss or cobwebs: thought to stop bleeding and help to clot.

Cauterization or branding: common for animal bites, believed to “burn out disease.”

Challenges

Poor hygiene in surgery and wound care.

No knowledge of germ theory. Healers treated most wounds based on appearance, not cause.

Superstition-based medicine. If the wound resisted healing, people might blame it on curses or demons.

Example: After being clawed by a wolf, a peasant’s wound is bound with moss and wrapped tight. The village healer chants prayers while leeches draw blood, but infection still sets in, leading to fever and hallucinations.

Contemporary Treatments

Today, doctors treat animal and human bite wounds as serious medical events, especially because of the infection risk.

Typical Treatments

Wound cleaning and debridement: removing damaged or infected tissue.

Antibiotics: first line defense against infection (e.g., amoxicillin-clavulanate).

Tetanus booster: especially for dirty, deep, or claw-inflicted wounds.

Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP): if the animal is unknown or rabid.

Surgical repair: if tendons, nerves, or organs are damaged.

Pain management and wound monitoring: long-term healing often requires follow-up care.

Doctors treat human bites especially cautiously because of high bacterial load and common infections like Eikenella, Staph, and Strep.

Example: A bear mauled a hiker. In the ER, medical staff irrigated their wounds with saline, x-rayed them for debris, and stitched them up. They’re given IV antibiotics, a rabies shot, and scheduled for plastic surgery.

Fantasy Treatments

Fantasy worlds can treat wounds in wildly creative ways, but they’re often shaped by historical parallels or deliberately defy them.

Treatment Options

Healing magic: Simple spells may close flesh but cannot repair internal trauma or remove infection. Powerful healing might require rare reagents (phoenix ash, dragon’s blood, etc.) or religious authority.

Alchemical salves and elixirs: Potions might speed healing or sterilize a wound, but could have side effects like fatigue, hallucination, or magical scarring.

Cursed or magical wounds: Claw marks from a demon may resist healing entirely or slowly turn the victim into something else unless a specific curse is lifted.

Herbalists and hedge witches: May rely on folk remedies and ancient forest knowledge, treating wounds with enchanted poultices or ceremonial cleansing.

Healing Limitations as Plot Devices

Healing may not work on wounds from enchanted creatures.

A wound may require a specific ritual, place, or object to be healed.

A prophecy or curse linked to the wound might consume the healer’s life force or cause magical healing to fail.

Example: A ranger clawed by a corrupted warg finds his wound festering with dark magic. Traditional healing fails. Only a moonlit ritual performed in a sacred glade can draw the rot from his flesh.

Science Fiction Treatments

In a sci-fi setting, technology can dramatically reduce the danger of bites and claw wounds or introduce entirely new complications.

Treatment Options

Nanobot repair systems: Microscopic machines clean, close, and rebuild tissue from within. May malfunction or become infected by biomechanical contaminants.

Auto-sealing synthetic skin: Medical patches that bind to damaged tissue and stimulate rapid regrowth. Used in field kits by soldiers or colonists.

Gene-repair therapy: In cases of venom or biological degradation, therapy may recode damaged cells. May trigger mutation or unexpected gene expression.

AI-guided surgery or injectables: Smart needles that find arteries or track infection in real-time. Injectable meds that stabilize, numb, and disinfect all in one.

Immuno-suppression or rejection risk: Hybrid wounds (from alien organisms or synthetic beasts) may resist treatment or confuse the immune system.

Example: A bounty hunter slashed by a genetically engineered predator uses a medkit to seal the wound with biofoam but later learns that the creature’s claw carried a neural toxin and only advanced neurosurgery on the outer rim can save him.

Plot and Character Ideas

Bites and claw wounds are primal, painful, and deeply symbolic. Whether inflicted by animals, monsters, or people, they’re not just injuries. They’re turning points. These wounds can leave lasting scars, both physical and emotional, and serve as potent metaphors for betrayal, transformation, trauma, or survival. In speculative fiction, they may also carry magic, curses, or infection, altering the very nature of the character.

Here are a variety of plot and character ideas centered on bite and claw wounds across contemporary, historical, fantasy, and science fiction genres.

The Infection That Isn’t Bacterial

Genre: Contemporary, Medical Thriller, Horror

Plot Idea: After being bitten by a seemingly normal animal, a character shows neurological or behavioral changes. Tests show no rabies, no infection, but something is wrong.

Character Angle: The wound becomes the center of a mystery. Was it a bio-engineered animal, or something supernatural? The character experiences hallucinations, memory loss, or strange compulsions. Their team/partner suspects that forces beyond scientific understanding have altered them.

Twist: The bite transmits a dormant ancestral memory, not a disease, one that awakens something long forgotten in human evolution.

The Beast Within

Genre: Fantasy, Dark Urban Fantasy

Plot Idea: A were-creature or demon clawed a character, and the wound doesn’t heal. As the moon cycles, they shift but not into a typical werewolf. Something older and stranger is stirring.

Character Angle: They seek a cure but find those who know the truth want them dead. The claw wound acts like a tether to the creature that marked them. Each transformation becomes harder to reverse, risking their identity and humanity.

Twist: The original creature wasn’t trying to infect them but to pass on a curse they could no longer carry.

The Healer’s Curse

Genre: Fantasy

Plot Idea: A cursed beast bites a magical healer while the healer is saving it, and the wound absorbs the curse. Now their magic only heals others at a substantial cost to themselves and the wound grows worse each time.

Character Angle: They must choose when and for whom they’ll sacrifice themselves. Others view their wound as a mark of sainthood or a death sentence. They begin to lose control of their healing powers, spreading decay instead.

Twist: The only way to heal themselves is to wound someone else with the same bite, forcing a moral reckoning.

Survivor or Monster?

Genre: Science Fiction, Military

Plot Idea: An alien creature mauled a soldier but survives. In the aftermath, their body begins to adapt – new senses, reflexes, even claws. But are they evolving… or being replaced?

Character Angle: They become a weapon, faster and stronger than before, but unpredictable. Their squad fears them; their command wants to weaponize or terminate them. They must decide: stay human or embrace the mutation?

Twist: Someone sent the alien to spread a symbiotic species, and the character may now hold the key to humanity’s survival or destruction.

The Bite That Started It All

Genre: Historical, Horror

Plot Idea: Investigators traced a plague ravaging a medieval village back to a single mysterious bite wound on a woman a strange creature attacked in the woods. The wound never closed and her presence spreads sickness.

Character Angle: She is both victim and potential cause of the plague. Her family hides her, believing she’s cursed but redeemable. Priests want her executed. A traveling doctor wants to study her.

Twist: The creature was not evil but divine, punishing the village for a hidden crime. The bite is not a disease, but a judgment.

The Price of Survival

Genre: Contemporary, Adventure

Plot Idea: After a plane crash or wilderness accident, a wild animal bit or clawed a character who was trying to protect someone else. They survive, but the wound changes how others see them.

Character Angle: They’re hailed as a hero, but suffer from trauma and disfigurement. Survivor’s guilt and media attention push them to the edge. The person they saved grows closer or more distant because of the wound.

Twist: The animal was defending its young, and the character realizes they weren’t the hero they thought they were.

The Ritual Scar

Genre: Epic Fantasy, Coming-of-Age

Plot Idea: A sacred rite of passage in a tribal or warrior society involves being clawed by a bonded beast. The wound creates a magical link, but only if the wound heals without corruption.

Character Angle: The character’s wound festers, meaning they’re either unworthy or cursed. Their bond with the beast is incomplete, causing dangerous side effects. They must prove themselves in another way, or risk exile.

Twist: The failed bond wasn’t their fault. The beast is dying, and the character must save it to heal themselves.

The Predator’s Mark

Genre: Urban Fantasy, Detective Noir

Plot Idea: A private investigator finds a victim with a distinctive claw wound, a pattern he recognizes from his own past. He suffered an attack years ago, but no one believed him.

Character Angle: He has a partial immunity or sensitivity to the creature because of his wound. The attacker is still out there, possibly watching him. Every new case brings him closer to finishing the hunt or becoming prey again.

Twist: He’s been unknowingly tracked for years. The original wound was a tag, not a mauling.

The Bite That Can’t Be Hidden

Genre: Romance, Suspense, Contemporary

Plot Idea: In a violent domestic altercation, someone bites a character. They escape and start a new life, but the scar becomes a flash point for intimacy and trust with a new partner.

Character Angle: They flinch at touch, avoid mirrors, and hide their wound. Their new partner notices, and the slow reveal becomes central to healing and connection. The past resurfaces when the abuser reappears.

Twist: The bite scar matches another recent case, revealing the abuser isn’t just a monster to them, but to others too.

The Self-Inflicted Claw

Genre: Psychological Horror, Supernatural

Plot Idea: A character wakes with deep claw marks on their own body with no memory of what caused them. The wounds keep reappearing, growing deeper, more intricate, and more ritualistic.

Character Angle: They suspect sleepwalking, possession, or something worse. No one believes them until others suffer similar marks. They begin to see things, fragments of other lives, creatures just out of view.

Twist: They are the vessel of an ancient predator and the claw wounds are its way of preparing the body for its final form.

Bite and claw wounds can be raw, personal, and terrifying, making them excellent narrative tools. Whether your character is battling a wild animal, an unhinged enemy, or a beast from another world, depicting the injury with realism and consequence will elevate your storytelling.

From infection to impairment, pain to psychological scars, these injuries mark characters – literally and metaphorically. Use them not just to hurt your characters, but to shape who they become after the bleeding stops.

I hope this was helpful. Let me know if you have questions or suggestions by using the Contact Me form on my website or by writing a comment. I post every Friday and would be grateful if you would share my content.

If you want my blog delivered straight to your inbox every month along with exclusive content and giveaways, please sign up for my email list here.

Let’s get writing!

Copyright © 2025 Rebecca Shedd. All rights reserved.

The Writer’s Guide to Stab Wounds

Posted on July 4, 2025 Leave a Comment

Stab wounds can be quick and deadly, slow and painful, or messy and traumatic depending on location, depth, weapon type, and the world your story inhabits. However, a well-written stabbing scene isn’t just about blood – realistic portrayal involves anatomy, physics, psychology, and consequences.

This guide will help you realistically depict stab wounds, explaining how injury severity, weapon characteristics, survival odds, and long-term effects should shape the narrative. I’ll also cover the important distinction between a puncture wound and a stab wound.

What’s the Difference Between a Puncture and a Stab?

Puncture Wound

A puncture wound is caused by a narrow, pointed object penetrating the skin (e.g., needles, nails, spikes). Minimal external bleeding, but high risk of deep internal damage or infection because the wound seals over quickly. Often small in surface area but deep, with a higher chance of invisible internal injuries.

Stab Wound

A stab wound is a deeper-than-wide injury caused by a bladed weapon, like a knife, dagger, or sword. Significant external and internal damage, depending on blade size and force. Typically, longer entry wounds than punctures, and often involve cutting and penetrating.

Quick Tip: A knife thrust into the belly? Stab wound.Stepping on a rusty nail? Puncture wound.

Key Factors That Determine Stab Wound Severity

Location on the Body

Where the character is stabbed dramatically influences their survival odds and consequences.

Chest: May puncture lungs, heart, or major arteries. Low odds if heart/lung is hit without immediate aid.

Abdomen: Risk of damage to intestines, liver, kidneys. Moderate odds; depends on internal bleeding or infection.

Neck: Risk to jugular veins, carotid artery, windpipe. Very low survival without immediate help.

Back: Can damage lungs, kidneys, spine. Moderate to low odds depending on area hit.

Arm/Leg: May hit muscles, arteries (like brachial or femoral). High odds, unless a major artery is cut.

Shoulder: Often survivable but can involve nerve damage. High odds with proper care.

Depth of the Wound

Shallow stabs (skin and fatty tissue): Painful but survivable with basic treatment.

Medium depth (muscle layer): More serious, impairing movement and strength; risks bleeding and infection.

Deep stabs (organs, arteries, bones): Life-threatening. Risk of shock, massive internal bleeding, or organ failure.

Penetrating stabs (full thrusts): Especially dangerous if the weapon passes through to vital organs or major vessels.

Quick Tip: A deep abdominal stab can lead to sepsis if the character survives the initial injury.

Type of Weapon

Straight Blades (e.g., dagger, stiletto, sword point): Designed for deep, clean thrusts. May cause narrow but deadly wounds, ideal for reaching vital organs quickly.

Serrated Blades (e.g., survival knives, combat knives): Tear tissue when entering or being pulled out. Harder to close surgically, leading to longer healing times and worse scars. Extraction often causes more damage than the stab itself.

Small Blades (e.g., kitchen knives, daggers): Penetration depends on force applied and target’s clothing/armor. Less likely to reach deep organs without significant force.

Large Blades (e.g., swords, bayonets, long knives): Greater range and potential for massive trauma, often causing gaping wounds rather than clean holes.

Quick Tip: A rapier thrust might cause a deep, fatal organ puncture. A serrated combat knife slash might cause a horrific, bleeding flesh wound with lasting nerve damage.

Immediate Effects of a Stab Wound

Sharp, immediate pain at the site of injury.

Bleeding, profuse if arteries or veins are hit.

Shock, the body’s response to trauma, can set in within minutes.

Difficulty breathing (if lungs are involved).

Paralysis or weakness (if spinal cord or major nerves are damaged).

Internal bleeding which may not be immediately visible.

Collapse, especially with chest, neck, or major abdominal wounds.

Quick Tip: Pain isn’t always instant. Shock and adrenaline can delay the pain for several minutes.

Survival Odds and Long-Term Effects

Survival Odds

High for limb wounds (unless major arteries are severed).

Moderate for abdominal wounds if medical treatment is rapid.

Low for chest or neck wounds involving vital organs.

Long-Term Effects

Chronic Pain: Nerve damage may cause lifelong issues.

Reduced Mobility: Shoulder, knee, or abdominal stabs may limit physical abilities.